The era of big data has transformed the Global South. Countries that remained offline for the previous centuries have gained access to digital data. Today, companies, policymakers, and humanitarians use data from the Global South as their competitive advantage (Taylor, 2017, p. 1). However, researchers in scientific communities have limited power to intervene with the issue of data justice in comparison to companies and governments (Taylor, 2017, p. 2).

Within the humanitarian world, international NGOs and humanitarian aid organisations collect data to serve their organisational purposes. Data such as biometrics and E-ID are being collected without the consent of individuals from the affected regions (Squire & Alozie, 2023, p. 5). Also, humanitarian data is used by aid organisations to get funding, increase visibility, and gain power (The University of Warwick, 2022).

Currently, data discrimination is advancing. Thus, regulations would have to be implemented to ensure that data justice and ethical concerns are at the forefront of the agenda to ensure people are visible, represented, seen and heard.

The aim of this blog article is not to solve the data inequity or injustices within humanitarian organisations. Instead, this article aims to heighten the awareness of humanitarian practitioners when possessing data on individuals from the global south. First, opportunities and threats to humanitarian data will be identified. Then, recommendations for ethical and moral best practices will be discussed. Lastly, concluding reflections on the HumanitarAI blog and my professional practice will be given.

To understand the ethical concerns of AI and datafication, the technological advancements since the 1990s and a short example of the application of AI in the humanitarian field will be given.

Data transformation in humanitarian work: Technological Advancements since the 1990s

Similar to organisations and governments, information technologies and data have radically transformed the humanitarian field since the 1990s, becoming a key component of humanitarian work (Vinck et al., 2019, p. 1). As organisations continue to accelerate in the digital era, the usage of cell phones and social media has increased. Also, datafication has enabled organisations to discover traits and aspects of social life that were not possible in the past (Van Dijck, 2014, p. 198). Besides, possession of the data enables organisations to predict user’s social, political and economic preferences. By having the user’s data, organisations could analyse data to create personal, customisable messages that are specifically designed for the audience (Van Dijck, 2014, p. 200).

In the current global context, the data has a large potential to be fed into Machine Learning and Algorithmic systems that could execute complex tasks beyond human capability (Pizzi et al., 2020, p. 150). ChatGPT and AI Sandboxes can now produce speeches, images, press releases, content and audio. The broad range of AI tools can create content at unprecedented speeds.

AI and data use cases in the humanitarian field

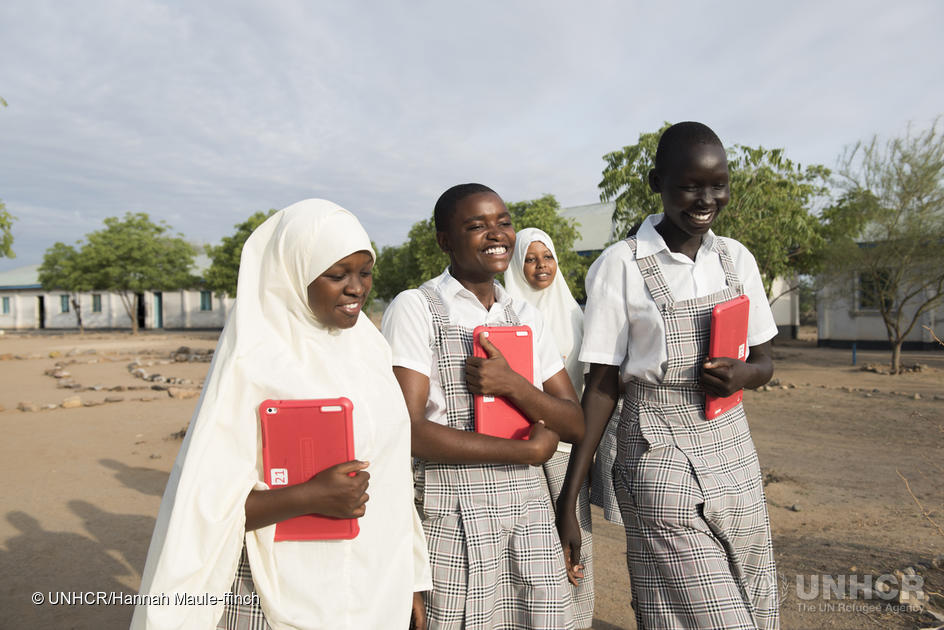

Humanitarian organisations such as ICRC, UNHCR and the International Rescue Committee are now using AI and Machine Learning for their projects, especially to create tailor-made solutions for refugees, crises and learning experiences for children (Toplic, 2020). Current AI/ML initiatives claim to help NGOs and humanitarian organisations quickly find information, efficiently work within teams, speed up the decision-making processes, and develop emergency and disaster plans (Toplic, 2020).

In UNHCR, early warning systems are being developed to provide services to displaced refugees. These warning systems will help NGOs, Governments, and scholars identify the number of refugees to optimise their resources and aid allocation (Henningsen, 2023, pp. 1–2). However, this work to gather this data is time intensive as why people move away from their homes is a complex phenomenon (Henningsen, 2023, p. 2). Current work in this area includes the IP address and personal log-in information of citizens to track their precise locations from Yahoo and Skype (Henningsen, 2023, p. 18). By having this data, UNHCR has the opportunity to plan and develop early warnings efficiently.

As AI and big data are developing at unprecedented speeds, current scholars are increasing the number of research in this field to determine the effectiveness of use cases. However, data must be strictly and ethically monitored (Kondraganti et al., 2022, p. 25). The next section of the blog will dive deeper into the ethical concerns of big data and AI for humanitarian aid practitioners.

Ethical concerns for the global south

Concern 1. Worldwide technology adoption will continue to grow, leading more countries to track, monitor and trace citizens in almost every facet of their lives.

In the Global North countries, the European Commission worked closely with Tilburg University to frame informational rights and freedoms (European Research Council, 2018). However, academic literature on data justice has only begun since 2014.

As data collection continues to grow globally, democratic societies must ensure data is collected and distributed fairly (Cinnamon, 2019, p. 215). Fostering awareness of data and understanding its potential and limitations are essential to AI Ethics. Not only is there inequality in our societies now, but AI could aggravate it further,

“There is also a risk of growing inequality. Major gaps are already opening up between the data haves and have-nots. Without action, a whole new inequality frontier will open up, splitting the world between those who know, and those who do not. Many people are excluded from the new world of data and information by language, poverty, lack of education, lack of technology infrastructure, remoteness or prejudice and discrimination”

(UN Data Revolution Group, 2014, p. 7).

Concern 2. Data such as biometrics and E-ID are being collected without the consent of individuals from the affected regions (Squire & Alozie, 2023, p. 5).

By possessing sensitive data of individuals, humanitarian organisations can speak on behalf of the citizens. This activity takes away the rights and freedom of citizens to make a valid judgment (Squire & Alozie, 2023, p. 2).

Humanitarian organisations that claim to “do good” are attracting donors by gathering more data to have the latest insights on disaster response and philanthropic activities. They have an economic purpose in fighting for the data in the most remote areas and communities because whoever is the champion in this race is the one who gets the funding at the end (Squire & Alozie, 2023, pp. 3–4).

As the data collection from individuals is without consent, this is a form of coloniality of humanitarianism. The fact that the data is collected, analysed and further amplified to generate profits is an act of colonialism. Unfortunately, this selfish pursuit of economic opportunism is a form of colonialism that continues to live in our modern societies and organisations, leading to a significant problem, especially in aid organisations that claim to “do good”.

Just as critical infrastructures of cities such as railways, ports and monuments are taken away from indigenous populations during colonialism, information is stolen from these vulnerable populations, thereby leading to economic and social inequality.

Concern 3. Amid technological development and datafication, humanitarian data is used to get funding, increase visibility, and gain power (The University of Warwick, 2022).

Just as critical infrastructures of cities such as railways, ports and monuments are taken away from indigenous populations during colonialism, information is stolen from these vulnerable populations, thereby leading to economic and social inequality.

Circling back to my previous blog post on AI equity at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, I used data to discuss the inequalities of philanthropic and aid organisations. I have discovered that getting cutting-edge data is something even researchers in advanced settings compete for, constituting forms of inequality even amongst the elites.

In the humanitarian context, communication practitioners can gather reports and analyses and get their requests for funding approved by possessing the latest data. As there are many global inequalities and injustices left unsolved, the data regulations must be kept in place, especially in the Global South. Here are some future solutions to tackle these ethical concerns,

Future solutions and existing ways to tackle ethical concerns

To tackle the ethical concerns of AI, here are five future solutions humanitarian practitioners could use.

Solution 1. Proposing a framework for data justice

Invented by Taylor (2017, pp. 8–9), this framework aims to understand the potential and threats of datification and AI whilst catching up with the speed of technological development. When developing such a framework, it should consider the people from the global south and be fairly adopted worldwide (Taylor, 2017, p. 8).

Solution 2. Actively listening and fundamentally changing humanitarian ethics

As technological developments are accelerating, humanitarian ethics could be revised by actively listening to the demands of affected communities (Squire & Alozie, 2023, p. 10). Here are three easy hacks practitioners could explore:

- Collect data on an open-source platform. This will increase data visibility.

- Introduce humanitarian ethics, guidelines and principles on an organisational level.

- Remove paternalistic styles of managing data and eliminate colonial dynamics within the existing organisation.

Solution 3. Develop solid AI principles in a proactive manner

As practitioners often lack direction when it comes to AI and data justice, giving out codes/guidelines to AI practitioners at every stage of the AI life cycle will help to provide guidance (Pizzi et al., 2020, pp. 168–169). This will enhance digital cooperation on a global level during decision-making and policymaking processes. According to Pizzi et al. (2020, p. 169), AI principles should be “trustworthy, human-rights based, safe and sustainable and promotes peace” (Pizzi et al., 2020, p. 169).

Solution 4. Introduce and enforce data policies that respect the individual’s human rights (Vinck et al., 2019, pp. 9–10).

When implementing data policies, make individuals aware of how their data could be shared with others. In many cases, data could also be collected without directly approaching the person who possesses the data. Thus, this data could also reach different groups and generate insights for researchers and organisations from the Global North.

Solution 5. Researchers to ethically reflect on big data and AI

Apart from communication practitioners in the field, academic researchers also have the responsibility to reflect on the social, cultural and ethical implications of big data and AI projects. Researchers could be responsible by conducting interdisciplinary research and connecting stakeholders to deeply reflect and scrutinise what datafication means in the global South context (Van Dijck, 2014, p. 206). Further, they could invite different fields of experts to examine the different angles and ask different questions. This will help develop inclusive data/AI principles and frameworks (Van Dijck, 2014, p. 202). Lastly, research validity could be improved by combining quantitative data sets with qualitative questions and by questioning the ethical and social aspects of the studies to reduce biases in data (Van Dijck, 2014, p. 206).

Concluding reflections

Through this blogging exercise, I have learned three key lessons.

First, project management and effective communication are critical to a good blog. As most people in this Master’s course are communication practitioners and executives who work 24/7. Our time limits the work we can produce. Thus, project management practices such as making an agenda before meetings, setting up a tracker and following up rigidly with a timeline are essential to delivering good work. Also, weekly/bi-weekly catch-ups are a great way to get the whole team up to speed. By being on the same page, we understand the resources, time and efforts needed to produce.

Second, my current work at Weber Shandwick is focused on healthcare, AI and development. Some clients from the UN are also talking about health equity, disaster response and digital health. As we are advancing rapidly on the tech and AI parts, it is crucial to stay informed about the do’s and don’t, as well as the potentials and threats of datafication and AI. When building corporate image, thought leadership and organisation narratives, not only is it essential to flag unethical practices, but also to set up a guide in data justice to educate the industry practitioners on what data justice is in layman’s terms.

Lastly, blogging is a great way to reflect and stay updated on a specific topic. Blogging is an enriching experience, allowing us to gather thoughts and knowledge in small doses. After several weeks of blogging, I am convinced to begin my blog. Once the blog was set, I realised it was not only about the formatting and visual layouts. However, blogging is about gathering data, analysing data and putting some profound reflections on a specific topic. As I continue my journey in communication for development in both academic and professional paths, I am convinced that blogging is one of the best ways to stay updated and have an “educated” opinion about global issues. If blogging is too time-consuming, check out micro-blogging here.

Thanks for reading, and see you next time.

References

Boyd, D., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2012.678878

Cinnamon, J. (2019). Data inequalities and why they matter for development. Information Technology for Development, 26(2), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1650244

European Research Council. (2018). Global data justice in the era of big data: toward an inclusive framing of informational rights and freedoms. https://doi.org/10.3030/757247

Henningsen, G. (2023). Big data for the prediction of forced displacement. International Migration Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231195296

International Telecommunication Union. (2022). Facts and Figures 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2023, from https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/facts-figures-2022/

Kondraganti, A., Narayanamurthy, G., & Sharifi, H. (2022). A systematic literature review on the use of big data analytics in humanitarian and disaster operations. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04904-z

Pizzi, M., Romanoff, M., & Engelhardt, T. (2020). AI for humanitarian action: Human rights and ethics. International Review of the Red Cross, 102(913), 145–180. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1816383121000011

Squire, V., & Alozie, M. T. (2023). Coloniality and frictions: Data-driven humanitarianism in North-Eastern Nigeria and South Sudan. Big Data & Society, 10(1), 205395172311631. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517231163171

Taylor, L. (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 205395171773633. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717736335

The University of Warwick. (2022). Datafication of the humanitarian sector: Efficacy and ethics [Press release]. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/research/projects/internationalrelationssecurity/dataanddisplacement/data-displacement/news/20221109-policy_brief_datafication.pdf

Toplic, L. (2020). AI in the Humanitarian Sector. NetHope. https://nethope.org/articles/ai-in-the-humanitarian-sector/

UN Data Revolution Group. (2014). A World that Counts: Mobilising the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. Geneva: United Nations Secretary General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group. https://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf

Van Dijck, J. (2014). Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big Data between scientific paradigm and ideology. Surveillance and Society, 12(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776

Vinck, P., Pham, P., & Salah, A. A. (2019). “Do no Harm” in the age of big data: data, ethics, and the refugees. In Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12554-7_5