In recent years, there has been more discussion and critical analysis surrounding the intersections of afropessimism, datafication, and continual coloniality in development. These complex and interconnected issues shed light on the persistent challenges faced by African nations and communities in the era of data-driven economies and global development.

Afropessimism and “Arrested Development”

Afropessimism, as a theoretical framework, highlights the enduring legacy of anti-Blackness and the ongoing oppression and marginalisation experienced by African-descended people. It critically examines how Blackness is constructed as a social category that is fundamentally excluded and devalued within dominant systems of power. Afropessimism, as defined by the Afro-Pessimist Scholars, is centred on the African American experiences, which homogenises the experience of all black people and excludes other non-white people (Douglass et al., 2018). However, afropessimism, in the development context, applies to the perception of Africa and its progress post-colonialism. Afropessimism is a term that describes a negative and often overly critical view of Africa, particularly concerning poverty, conflict, corruption, poor leadership, political instability, parlous economy, infectious diseases and underdevelopment. It tends to emphasise the challenges and problems facing African nations, unconsciously leading to the perception that development in Africa is impossible or difficult to achieve. This perspective has had implications for foreign aid, investment, and international policies towards Africa, potentially leading to reduced support and resources. When considering the implications of datafication and continual coloniality, it becomes apparent how these dynamics exacerbate and perpetuate the afropessimistic condition.

The Afropessimist view emphasises the belief that Africa is disadvantaged and may never overcome the challenges it faces. Related to Afropessimism is “arrested development”, which is a concept customarily used to describe a situation where a country or region’s economic and social progress has stagnated or been hindered by various factors. In the African countries’ context, it suggests that there were initial stages of development or progress which were halted or slowed down due to factors such as political instability, conflict or economic mismanagement. Most literature on development studies has focused on the economic dimension where development brings about social change with an associated rise in the level and quality of life, creation and expansion of income opportunities, and perhaps stewardship of the environment. Based on this definition of development, it does appear that Africa has indeed been in a state of minor to no economic growth, but this ignores the fact that African countries are diverse, and a wide range of factors influences their development trajectories. Discussions about development in Africa should be addressed in each country’s unique context with its own challenges and opportunities. Although these two concepts, Afropessimism and “arrested development”, simplify the issues affecting the continent and may fail to capture the actual nuanced realities, the nature of aid to Africa somehow reinforces the idea of dependency with outcomes dedicated or desired by the donors.

Datafication and its role in Development

Datafication, the process of transforming various aspects of social life into data that can be quantified, analysed, and used for decision-making, has become increasingly prevalent in today’s digital society. Data is generated at an unprecedented rate through various technologies, such as social media, smartphones, IoT devices and more. The data is stored, processed, and used by corporations, governments, and other institutions to inform their actions. However, datafication is not a neutral process. It is deeply intertwined with power dynamics and often reinforces existing inequalities. Datafication is associated with data capitalism, which is defined as “an economic model built on the extraction and commodification of data and the use of big data and algorithms as tools to concentrate and consolidate power in ways that dramatically increase inequality along lines of race, class, gender, and disability.” (Data For Black Lives, 2021)

Data is often centralised in the hands of a few powerful corporations and governments, creating an information hierarchy that parallels the colonial hierarchy of power. In the context of African development, datafication can serve as a mechanism for further marginalisation and exploitation. It can reinforce existing power imbalances, perpetuate stereotypes, and hinder the agency and self-determination of African communities.

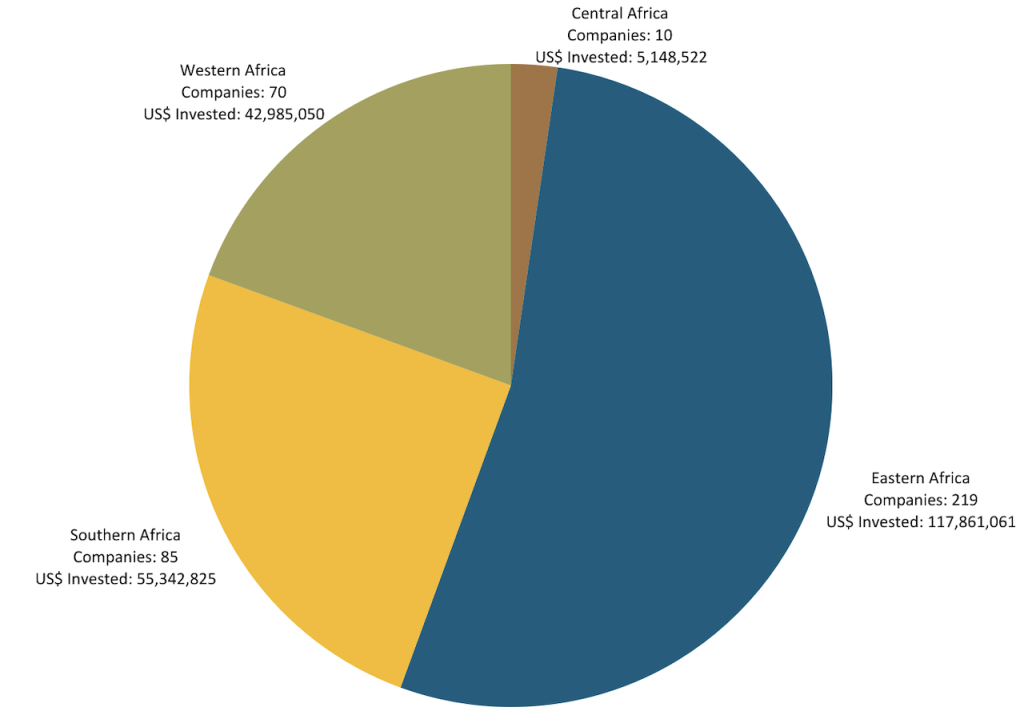

Datafication is used as part of the criteria for investors participating in projects run by organisations such as the Africa Enterprise Challenge Fund (AECF). The Africa Enterprise Challenge Fund is a non-profit development organisation that helps fund and support businesses as a way of reducing poverty and creating jobs. It has been in operation for over 15 years in Sub-Saharan Africa, creating an impact in 26 countries (AECF, 2023). Availability of data is one of the ways donors and investors can determine whether to fund development projects or not. However, the selection of regions for development is chosen based on the viability of the projects, the security in the region, and the return on investment, thus foregoing the paramount tenet of development aid, which is to focus on the needs of the people.

Coloniality of Power in Africa’s Development

Coloniality, also known as coloniality of power, a concept developed by scholars such as Anibal Quijano and Walter Mignolo, refers to the enduring, colonial-like structures, ideologies and power dynamics in contemporary society that persist even after formal colonialism has ended.

“In fact, if we observe the main lines of exploitation and social domination on a global scale, the main lines of world power today, and the distribution of resources and work among the world population, it is very clear that the large majority of the exploited, the dominated, the discriminated against, are precisely the members of the ‘races’, ‘ethnies’, or ‘nations’ into which the colonised populations, were categorised in the formative process of that world power, from the conquest of America and onward.” (Quijano, 2007).

Despite formal decolonisation processes, many African nations continue to grapple with the legacies of colonial rule, which have shaped their socio-political, economic, and cultural landscapes. A report on the SADC region shows growing inequalities and fragile democratic institutions that originated in the colonial era.

“Southern Africa features some of the world’s most unequal societies, characterised by enormous social cleavages that were shaped by settler colonialism and racial segregation and that have been sustained in the post-colonial period. It is therefore unsurprising that socio-economic grievances should not only impinge on human security but also represent a formidable challenge to peace and stability in the region in the long term” (Aeby, 2019).

There are many examples that seem to confirm the stereotypical view of Africa. For example, consider this occurrence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where a contract for gas extraction was awarded to a company with little to no expertise in the extraction of gas and environmental safeguarding (Rolley, 2023). Is corruption in state projects a unique feature of developing countries, vis-a-vis African countries? Contrast the perception of corruption in African countries to the procurement processes in the EU during the COVID pandemic, which displayed similar corruptive processes (Transparency International, 2021). However, this is not a competition about who is more corrupt or whether similar practices are present in the Global North. The prevalence of corruption in resource-abundant countries in Africa can be seen through the so-called rentier state effect, which states that:

“Problems arise in resource-rich states because the rulers are able to generate wealth through undisclosed resource rents – or sovereign rents, as Collier (2005) refers to them – rather than through taxation. In simple terms, where governments rely on taxation as their primary source of revenue and where there are relatively fair elections, supplying public goods drives political competition. There is, therefore, dependence in the political process on broad-based public sentiment and proclivity for those seeking or maintaining political power to engage in rent-producing activities as a result” (Standing, 2007).

The political class maintains power by controlling revenues from the extraction and processing of resources from state-run organisations. To augment this view further, most of the crises in African states seem to stem from the low quality of governance and democracy:

“Most of the acute intrastate crises of the last ten years in SADC countries have been prompted by matters of governance, including electoral stalemates, authoritarian rule, government unaccountability, and the abuse of state resources for the preservation of power. These are equally rooted in the violent struggles of the past”(Aeby, 2019). This further affirms the impact that coloniality of power has on the ongoing development challenges in Africa.

Digital Colonisation and Data Justice

Digital colonisation, a form of datafication, implies a digital divide where certain groups lack access to technology and the benefits of data-driven decision-making, mirroring historical patterns of colonisation and exclusion from resources and opportunities. There is a growing trend in digitalisation of the AID industry where the use of digital tools and data is a requirement. The use of digital tools is not necessarily harmful. It enables the development actors better ways to communicate, track and analyse the development projects. However, the push towards extensive datafication in the Global South has resulted in disquiet as it evokes images of colonialism and imperialism. The Randomistas, as discussed by Adam Fejerskov (2022) feature prominently in the datafication and experimentation of the Global South (de Souza Leão et al., 2020).

“A striking feature of contemporary humanitarianism then is its experimental turn. Humanitarian actors have turned to new and, in some instances, unproven and untested approaches and technologies, partly because of a growing pressure on them to do more with less resources and partly because of a growing fashion for the sector to ‘innovate itself’ through datafication and digitisation” (Fejerskov, 2022).

The drive towards experimentation and datafication is resulting in divisions between different regions, with data-poor countries needing more resources as the donors and their partners prefer to work with countries where development can be measured and evaluated,i.e. Countries with data-a-plenty (Cinnamon, 2020). There is a danger that the safeguards or data justice concerns of the citizens in the Global South are ignored in favour of economic outcomes. That datafication processes can amplify existing inequalities by perpetuating biases present in the data is elucidated by Safiya Noble in the following passage:

“While we often think of terms such as “big data” and “algorithms” as being benign, neutral, or objective, they are anything but. The people who make these decisions hold all types of values, many of which openly promote racism, sexism, and false notions of meritocracy, which is well documented in studies of Silicon Valley and other tech corridors” (Noble, 2018).

Afropessimism calls for critical engagement with data practices and a commitment to data justice, ensuring that data is collected, analysed, and utilised in ways that are ethical, inclusive, and empowering. It necessitates challenging the underlying power structures and ideologies that perpetuate coloniality and working towards decolonised approaches to development that prioritise equity, justice, and self-determination. This view is reflected by Abeba Birhane (2019), where she says – “In a continent where much of the narrative is hindered by negative images such as migration, drought, and poverty, using AI to solve our problems ourselves means using AI in a way we want, to understand who we are and how we want to be understood and perceived: a continent where community values triumph and nobody is left behind” (Birhane, 2019).

Conclusion

The essay has provided a critical lens through which to examine the complexities and challenges faced by African nations and communities in their pursuit of sustainable and inclusive development. The interactions between afropessimism, datafication and continual coloniality in development highlight the urgent need for a paradigm shift in how we approach and address the complexities of development in African nations and communities. It is crucial to have ongoing conversations and dialogues that further explore these topics and their implications. By fostering a deeper understanding of afropessimism, datafication, and continual coloniality, we can collectively work towards dismantling the systems of power and oppression that perpetuate inequalities and hinder development. This requires a commitment to ongoing education, research, and activism to challenge the status quo and advocate for transformative change. It also calls for a reevaluation of power dynamics, data practices, and the underlying structures that perpetuate coloniality.

Final Thoughts on the Module

The course was challenging as it involved the management of the media platform, WordPress, research for articles to publish, and at the same time handling everyday issues such as work and home life. One of the interesting aspects of the course was the production of articles that fit a particular theme, which in my case was Afropessimism. The key is to bear in mind the target audience and how to formulate topics to engage and stimulate discussions. However, there is a requirement to engage with the major media platforms (Meta, X-Twitter, Reddit) in order to spread the message. This may go against one’s view of social media. The various techniques explored in the module on how to use images, videos and simple text to convey a message to the audience are applicable to most business and social situations. Another important aspect that came through was how to work together in a group when members come from diverse backgrounds with different levels of experience and expectations. Sometimes, the free-flow democratic design and implementation decisions process does not work. It is thus important to quickly establish group dynamics but also be flexible enough to adapt to change.

Bibliography

Aeby, Michael, “SADC – The Southern Arrested Development Community? Enduring Challenges to Peace and Security in Southern Africa, 2019, The Nordic Africa Institute, https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1351257/FULLTEXT01.pdf, pp17,38

Africa Enterprise Challenge Fund, 2023, https://aecfafrica.org

Aníbal Quijano (2007) COLONIALITY AND MODERNITY/RATIONALITY , Cultural Studies, 21:2-3, 168-178, DOI: 10.1080/09502380601164353

Birhane, Abeba, July 18, 2019, “The Algorithmic Colonisation of Africa”, https://reallifemag.com/the-algorithmic-colonization-of-africa/

Cinnamon , Jonathan (2020) Data inequalities and why they matter for development, Information Technology for Development, 26:2, 214-233, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2019.1650244

Data For Black Lives, May 17,2021, “Data Capitalism and Algorithmic Racism”, https://d4bl.org/reports/7-data-capitalism-and-algorithmic-racism, pp4

Douglass, Patrice , Terrefe, Selamawit D. , & Wilderson, Frank B. (2018). Afro-Pessimism. obo in African American Studies. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780190280024-0056

De Souza Leão Luciana, Gil Eyal, 2020, “Searching under the streetlight: A historical perspective on the rise of randomistas, World Development”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.10478

Eubanks, V. (2018). “Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor.” St. Martin’s Press.

Fejerskov, Adam, 2022, The Global Lab: inequality, technology, & the new experimental movement, Oxford University Press, pp.20

Noble, Umoja Safiya (2018), “Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism”, NYU Press, pp.16

Rolley, Sonia. ‘Exclusive: Firm Chosen to Extract Gas from Congo’s Lake Kivu Failed Criteria’. Reuters, 2 November 2023, sec. Africa. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/canadian-winner-gas-rights-congos-killer-lake-kivu-failed-criteria-2023-11-02/.

Standing Andre, October, 2007, “Corruption and the extractive industries in Africa”, Institute For Security Studies, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/98941/PAPER153.pdf

Transparency International, 2021, “EU Residents See Corruption in Public Contracting”, https://www.transparency.org/en/news/gcb-eu-2021-public-contracting-bribery-connections-corruption-trust-integrity-pacts

Wilderson, Frank B. “Afro-Pessimism and the End of Redemption”, 2015, https://humanitiesfutures.org/papers/afro-pessimism-end-redemption/

World Health Organization (WHO), May 3, 2023, “Data-Driven Development: How Rwanda is Pioneering Health Information Systems for Improved SDG Monitoring” https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/data-driven-development-rwanda-pioneering-health-information-systems-improved-monitoring