Back in 2017 my sister gifted to me on Christmas eve a red plastic folder that contained 20 black and white photocopied pages of writing. At the edge of each page was a stamp that read “property of SOAS university”. Confused as to why these pages were given to me as a gift my sister explained that they were copies of Apolinario Mabini’s collection of speeches that cover the progression and dissolution of the Philippine revolution (1896-1898). (Mabini was the first Prime Minister of the First Philippine Republic, which was established after 400 years of Spanish colonial rule and eradicated when the United States of America purchased the Philippines for 20 million USD via the Treaty of Paris 1898.)

The excitement in my sister’s voice reflected her discovery of a valuable piece of historic information and the pleasure in her rebellion in making copies of the pages. The collection of writings reflect the intellect, organization and connectedness of the revolutionary government of the Philippines in their effort to liberate themselves from Spanish colonial rule.

In both my sister’s and my own education in the Philippines we had never come across these writings in our history classes. There are of a plethora of reasons for this, many of which are typical for a post-colonial country. Firstly, the educational system of the Philippines battles with different narratives of national history. Perspectives on the occupation and impact by the colonizers vary from admiration and respect to indifference and vexation. Secondly, as a result of colonization the different economic classes in the Philippines hold varying degrees of closeness to colonial narratives – with the upper class educated in and by foreign standards – accepting without questioning colonial accounts of history. The social class you belong to will dictate the school you go to, and subsequently the curriculum you are taught. Lastly, there is the aspect of accessibility. Materials and objects that are of importance to national history and collective memory are not always accessible to schools and teachers across the country. Many important texts, artefacts and objects are not even in the possession of the national archives, libraries or museums but stored in the archives of the former colonizing countries, or even at times in the private homes of wealthy foreign elite.

Reading the writings of Mabini at age 25 radically changed my understanding of the Philippine revolution and my perception of the Filipino identity. This blog entry explores the politics of archiving and how new media is opening up new forms of cataloguing information, amplifying decolonized discourse building.

Why is decolonization relevant to development?

Critical development scholars like Craggs (Development in a global historical context, 2014) have illustrated the historical ties development has to the colonial era, problematizing contemporary north-south relations. Examining not only the era of liberation of post-colonial countries but also the circumstances of colonization and how this contributed to the development of the global north posits development discourse (and practice) in a different light. It becomes not so straight forward as believing that development is simply a question of economic growth, improvement of infrastructure, diffusion of innovation nor provision of basic services. Instead the concept of development is contextualized, politicized and examined, raising questions like: who defines and enables development; how does development perpetuate old systems of dependence and/or oppression; how does development continue to perpetuate the Other? (hooks).

It is worth examining how the formation of knowledge over the so-called developing world and its peoples has come to be. This can be done through the lens of decolonization. Decolonization refers not only to post World War Two when countries across Africa, Asia and South America won their independence but extends to the process of examining how colonizing practices are still present today in institutions that shape society. Decolonization also refer to challenging these structures by bringing forward alternative narratives and ways of thinking. Movements of decolonizing education have spread across the globe in recent years, starting with the Rhodes Must Fall movement in South Africa which sparked similar movements in Oxford, LSE and Cambridge in the UK. Decolonizing academic spaces and curriculum should be regarded as the starting point for deconstructing power dynamics and problematic interventions of the development and aid sector.

A curriculum provides a way of identifying the knowledge we value. It structures the ways in which we are taught to think and talk about the world. As education has become increasingly global, communities have challenged the widespread assumption that the most valuable knowledge and the most valuable ways of teaching and learning come from a single European tradition. Decolonizing learning prompts us to consider everything we study from new perspectives. It draws attention to how often the only world view presented to learners is male, white, and European. This isn’t simply about removing some content from the curriculum and replacing it with new content – it’s about considering multiple perspectives and making space to think carefully about what we value.

Open University, “The Innovating Pedagogy 2019”, 3.

Curriculum in itself is a tool of power, a tool of recognition. Excluding texts, objects and images that present alternative narratives shapes the way we account for our past, how we identify social challenges and how we conceptualize possible solutions.

The role of New Media

The proliferation of new media has an interesting role to play in the processes of examining, un-learning, re-conceptualizing and/or reclaiming narratives of identity, power and progress. Just as television in its heyday played a role in raising millions of youth across the globe social media with its extensive reach and habitual magnetism is undoubtedly influencing the youth and shaping our future. It is hard to say just how far reaching the impact of social media is, but we can already see that it has accelerated global communication dispersing ideas, belief systems and lifestyles across continents through a quick and constant flow of content.

What is especially interesting and empowering with social media is that the ramifications of control are subject to a different set of factors. For example, anyone can become an author, producer and publisher- placing content creation, and in a way the production of “informal” curricula, in the hands of individuals or organizations that historically have not had authoritative power. On Instagram I follow several journals that resurface, contextualize and re-publish material connected the history of African states and African diaspora. These journals are in effect building a body of knowledge that provide alternative world-views, historical accounts, values and frameworks of identity. One example is SUNU Journal.

SUNU Journal describes itself as “a collective, Pan-African platform for cultivating and archiving ideas concerning global Blackness across multiple forms + themes”. They publish new and old material from African scholars, artists, philosophers, political leaders, writers and more – accompanied by a curated text and image, and translations in French and Portuguese. At 108 thousand followers SUNU Journal is providing a free, open access archive on African history, written by Africans, to anyone who comes across their content. The archive itself is their website while they use Instagram as a tool for reaching audiences.

All rights: Sunu Journal

All rights: Sunu Journal

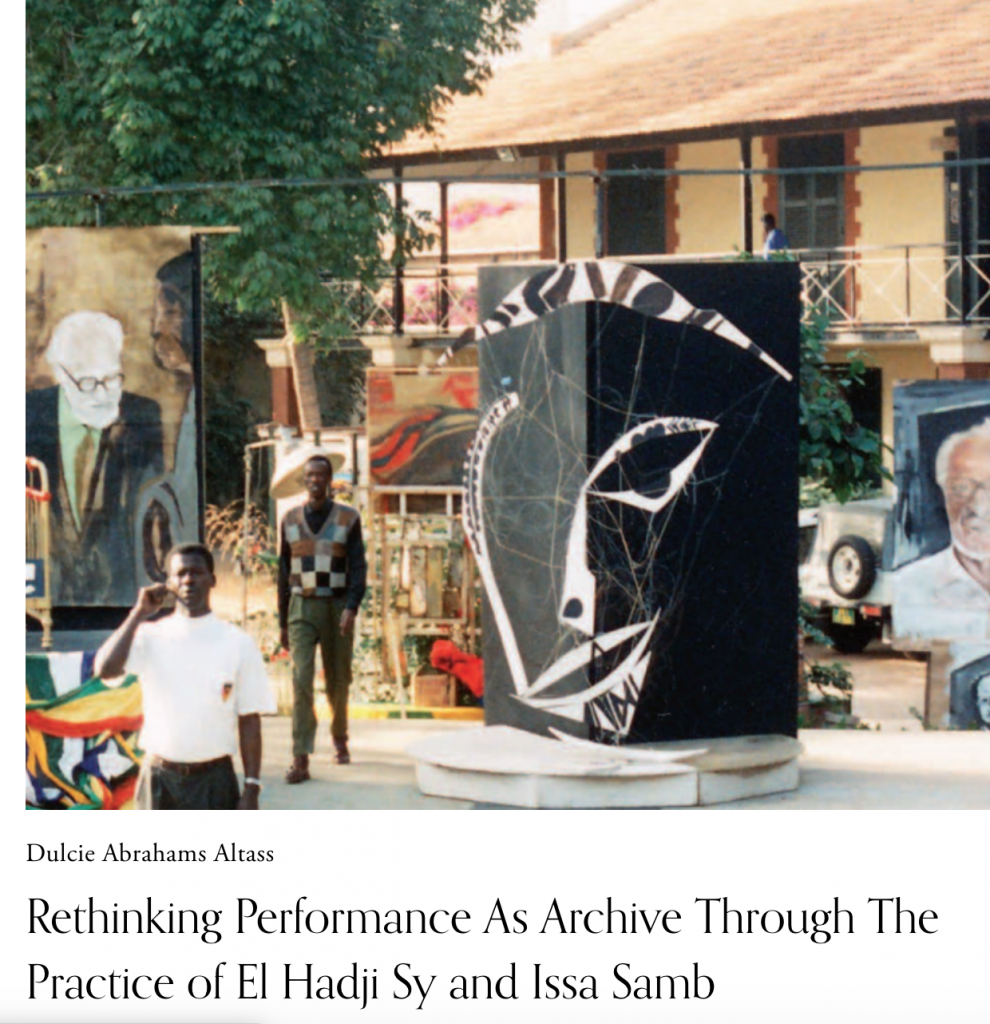

SUNU Journal writes and presents content in such a way that is accessible and interesting to an average reader. Their webpage is designed like a magazine, dedicating attention to aesthetics and visual pleasure. A combination of moving images, film excerpts and pictures against a black and white background encourages visitors to scroll further down their webpage. Content is classified into: essays, photography, art, conversations, film + video, poetry, short stories and reviews. These categories reflect and recognize the multiple dimensions where knowledge is produced, actively including art and culture as tools of discourse building. By comparison, traditional academic journals have a more limited scope to their content- requiring peer reviews, academic writing and strict referencing. These requirements effectively exclude material that do not conform to academic processes and leaves editorial control to institutions that are historically white and euro-centric (see Striphas).

Although SUNU journal does not adhere to the typical form and style of academic journals their intention is discursive. As their manifesto reads:

Bringing discourse into the arena of social media is definitely innovative. Considering that academic staff and researches are majority in the age group 40 and up (USA, Norway, UK) communicating stories of history, politics and social change on a platform whose users are in the age group 25-34 (statistica) is a new challenge that could bring transformative change.

A transformation of the traditional archive

Several interesting questions arise when we analyze archiving in the light of discourse making. What kind of materials merit preservation? Who controls, establishes and maintains the archive and in which ways do they do so? Who gets access to archived material? And to what extent do hierarchies of classification reflect social and political hierarchies? If we create archives outside of institutions what kind of body of knowledge will be produced, and who does it engage with? Archiving via new media presents new possibilities to the dispersal of knowledge – providing alternative sources than those prescribed by formal education.

SUNU Journal is just one of many digital archives using new media as a decolonizing tool. Chimurenga is another example of a self-organized, people powered publisher that dedicates space and recognition to non-western ways of thinking. These archives usher in a new tradition of recording art, intellect and objects that is isn’t bound to a physical archive and engages with the general public, rather than the academic elite. I am still searching for similar journals that make space for the Filipino and/or Asian narratives. Leave a comment below if you have any suggestions!