This blog post was written by Danielle Mbesherubusa Mittag and Nina Martin in conversation,

The project

Last week, two of the #Five4thePeople, Nina and Danie sat down (virtually!) for a conversation on the NonHuman Nonsense, a large-scope initiative by Leo Fidjeland’s and Linnea Våglund and their project Planetary Personhood in particular. The result of their exchange is summarized in what follows.

More information about the founders of the initiative is available here.

Imagine opening a six-pack egg tray to fix a quick spaghetti carbonara on yet another rushed weekday evening and realizing it is filled with six bright pink eggs. Not one, not two but six bright pink eggs? Or try visualizing yourself living in a world where meeting mosquitoes and… voluntarily feeding them is the norm. This ecosphere would be equipped with a “translator machine” that would bridge contact and perhaps even communication between mosquitoes and humans. The Pink Chicken and the Mosquito Translator projects are just two examples of how Fidjeland and Våglund seek to transmute our relationship to the non-human. It is part of the larger effort to work on embryonic stages of system transformation, in the realm of social dreaming and world-making processes. In the Pink Chicken project, the pair came up with the proposition “to genetically modify the bones and feathers of all chickens in the world to the color pink.” As far as I am concerned, their albeit speculative suggestion does a great job revealing how intimately linked social and ecological justice are. The project is framed as an activist campaign and/or startup and the idea is to allow us all to think about “the impact of novel biotechnologies from multiple ethical and political perspectives”. The questions they ask are scary and powerful all at once:

Why should we seek/avoid this future? How does the violence of entire-species genetic modification compare to the violence already inflicted on billions of chickens in factory farms? How can we have ethical relationships with other species in a shifting landscape of human-nonhuman power?

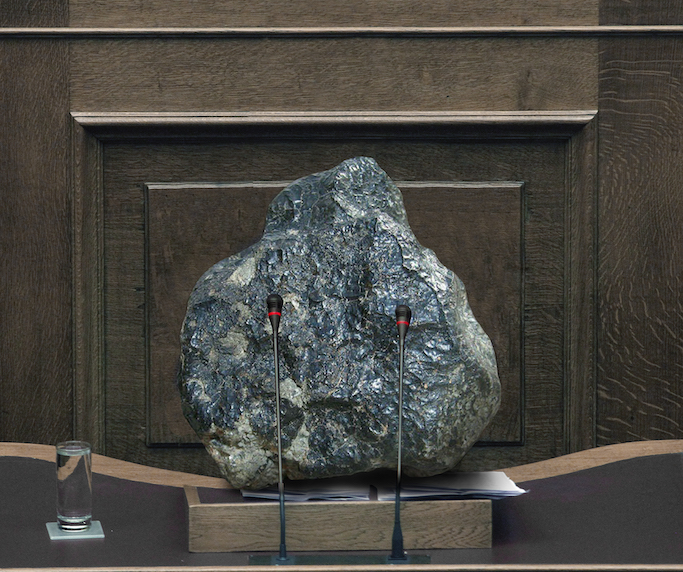

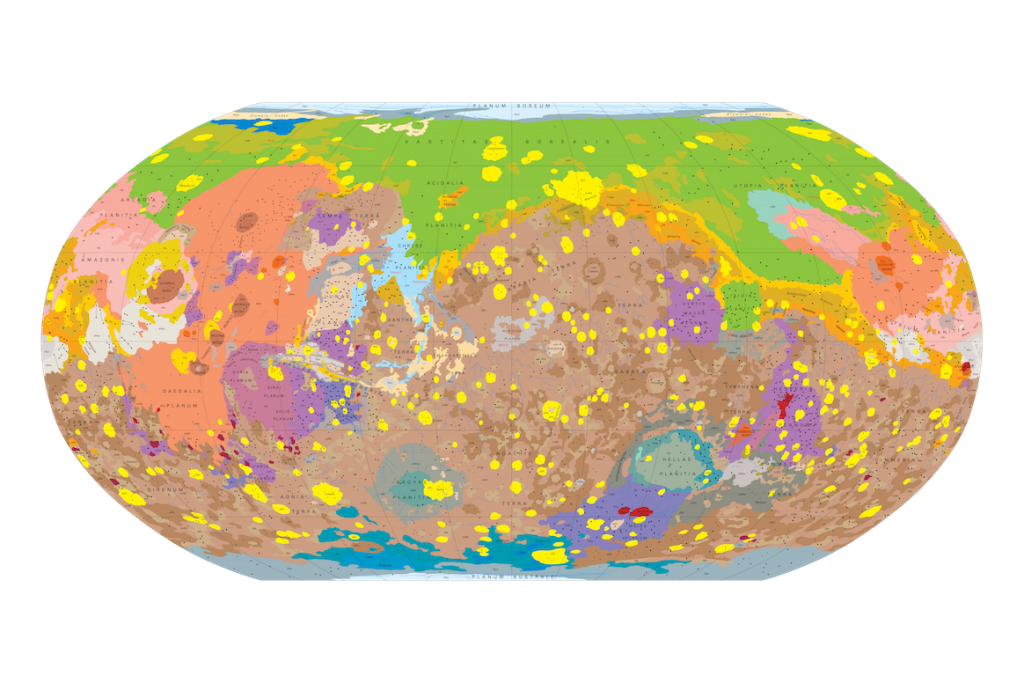

Their latest project Planetary Personhood launched virtually during the Dutch Design Week this month. As a project linking art and the sciences and a vast array of philosophical, even existential questions, it proposes a Universal Declaration of Martian Rights for a future and guardianship of Mars without colonisation, conquest and settlements, in an attempt to learn from the large errors of human history. By standing up for the immaterial, as “Martian Matter Matters”, they teach us a lesson of solidarity and empathy and take us on a journey of speculation. It is this project we take a closer look at in our conversation. Our readers should look at this as an effort to unpack the very dense Planetary Personhood project. A link to the project launch event and the Q&A with their viewers can be found below:

And please view the project video itself below to get a better understanding of the context.

The Conversation

Danie (DM): Thank you for introducing me to the Nonhuman Nonsense experiment and their project Planetary Personhood, Nina. This is such an interesting project. One that touches you in the gentlest possible way but that is so strong it feels as though it had hit you. I guess what I am trying to say is that these images, this world stays with you.

It is stated very early in the project’s presentation that the goal is “to transmute our relationship to the non-human, by embracing the contradictory and the paradoxical – telling stories that open the public imaginary to futures that currently seem impossible.”

It is perhaps a little strange that the first thought this evokes in me is a quote by Ruha Benjamin, i.e. “Remember to imagine and craft the worlds you cannot live without, just as you dismantle the ones you cannot live within.” In a way, Nonhuman Nonsense could be labeled as yet another grassroot effort aiming at disrupting the status quo. What similarities do you see between this and other “revolutionary” projects you are interested in? Revolutionary in quotes because this is not your usual, everyday kind of a revolution, is it?

Nina (NM): Thank you Danie, I think you found a really fitting link between Ruha Benjamin’s statement and the core mission of the group behind Nonhuman Nonsense. I actually think that by establishing a context and environment that we are not yet familiar with but embedding so many elements of discourses of our time they are paving the way to futures that do not require that we first dismantle oppressive structures of our societies but are instead fuelled by respect, empathy and solidarity in its purest forms.

Just like you are saying, their work, in this case the Planetary Personhood touches you subtly in many ways but it also comes with pretty straightforward elements. I am, in a way, reminded of more “usual” revolutions, be it the Black Lives Matter movement, the #OccupyWallstreet or the Standing Rock reservation’s protests #NoDAPL. All in all, I am reminded of the overarching movement to decolonise curricula worldwide and beyond Earth’s boundaries, I suppose.

On the other hand, it fits quite well into a form of New Media discursive storytelling I am interested in. From mainstream successes like the Black Mirror TV series to events such as NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism, I enjoy being transported into surreal, dystopian or even hyperrealistic surroundings that are strange and familiar at the same time to challenge the status quo.

I was pondering a bit on the term grassroots in that it is often used to refer to citizen movements to challenge a situation they find themselves in or to at least express allyship and solidarity to those oppressed by certain structures. This collective action is then to change the system from the bottom up, in turn mobilising society to lead to top-down changes in the system. While the motions of solidarity and allyship seem to be leading the cause of the project and I would identify it as quite revolutionary, I could not ascribe the term grassroots social movement to them as they may act on behalf of collective needs but without the masses, without the voices they uplift (Tufte 2017, Crossley 2002). Unless of course we consider, as they say, that we are basically “all made up of non-life entities, of mineral matter” hence supporting Mars, supporting inanimate matter is also supporting living beings and their future.

What were your first associations when experiencing this project?

DM: The alterations of our current geological epoch – the Anthropocene, our imprint on the Earth is so vast it sometimes feels impossible to fully grasp, leave alone to try to control. What strikes me most is that Fidjeland and Våglund’s response is to unbind certainty rather than bounding uncertainty. It feels like an attack at all fronts, but it is not an attack in the sense that it is not violent. On the contrary, Nonhuman Nonsense succeed in addressing important issues without one feeling pressured, as though it were only up to us humans to take action. The biggest lesson I take from the project is that of listening, of thinking and really just observing my surroundings. “Are we being good ancestors?” is a powerful question, one whose answer lies in a behavioural shift more than action only. Acting is a small fraction of the equation and I guess this is thanks to art for the most part.

Also, I am very attracted to the idea of multiple actions by multiple people rather than a limited number of actions decided by a few experts and policymakers or wealthy philanthropists. Fidjeland and Våglund’s suggestion is to network with other people and organizations who value a similar approach, what they call a public imaginary if I understood correctly, but we will come back to it.

The idea that we might be living in a “movement society” is far from being new (Neidhhardt and Rucht 2002, Melucci 1996, Meyer and Tarrow 1998 qtd. in Della Porta and Diani 2006:2). At the same time however, we seem to be in fairly new ground in the sense that this could be termed an artistic project as well as a scientific, philosophical and technological one. This brings me to my next question, which is perhaps linked to the first one. What is it about Nonhuman Nonsense that makes you think the project could be part of a wider social movement, one with a rather traditional way of revolutionizing things? Are there any specific movements in mind to which Nonhuman Nonsense could be said to be ramified?

NM: I do still feel that they are missing key elements to be considered a social movement but I do think that could well be under the umbrellas of existing movements or actually maybe they are, due to their surreal and yet universal messaging, the umbrella for such movements.

A revolution that they themselves point out in their project launch talk with its successive Q&A is the one to preserve nature on Earth. They refer to the way ecological movements must manoeuvre under this revolution as “collisions with Western systems” which I find really curious. One example is the Rights to Nature movement that assigns legal status/personhood to natural areas like mountains, lakes, forests and more. This idea of needing legal status, a passport, some document to hold on to one’s rights goes against many ways of ecological protection as handled by indigenous groups, however it seems to be the way to navigate a Western globalised world. So these examples to me also point out how difficult revolutions nowadays are. Dismantling an oppressive system is a rather complex task, one that maybe can only be done from within. Or can it? As Audre Lorde famously says: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

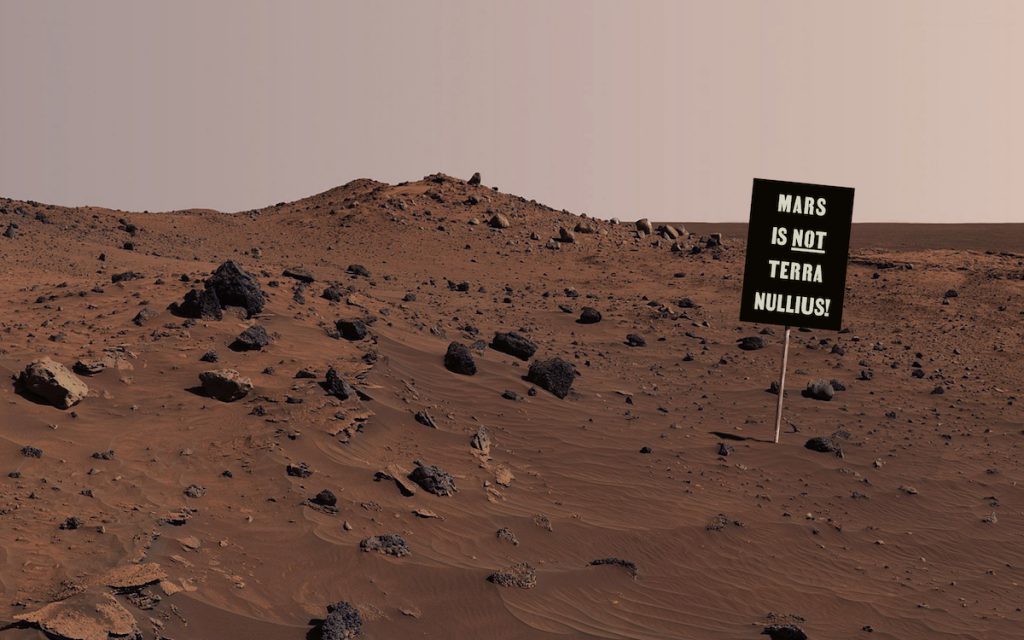

Additionally, the concept of rematriation is one that sticks out to me fairly often, referring to the acknowledgement of ancestry, of indigenous soil, of matriarchal structure and a (re-)distribution of wealth, basically restoring “to a spiritual way of life, in sacred relationship with their ancestral lands, without external interference.” (Newcomb, 1995, p.3). This concept stemming from indigenous knowledge systems is to me part of the ecological revolution as much as of a global decolonising movement without centring the colonisers or their power structures, as would be the case under a more capitalistic (and patriarchal) repatriation process. They refer to the colonial term “terra nullius” as used by settlers in modern-day Australia to declare a region void of agency, void of life, to spread their understanding of civilisation. A similar example they used was the expansion of settlers in modern-day USA that actually did not only led to ethnical cleansing of native tribes, the near extinction of the bison but also eroded the soil and decreased bio- and geodiversity along its path of so-called development and progress. In this way they are supporting the notion that “development” or the supporting industry is a neocolonial project. Development as an intentional practice guided by capitalist belief systems (McEwan, 2019, p. 100) was often a mere rebranding of the former colonial studies, taught and executed by the same persons under a new terminology (Eyben, 2014, p.38), hence leading to the same “extractivist mindset” of utilising local resources to achieve their own definitions of progress.

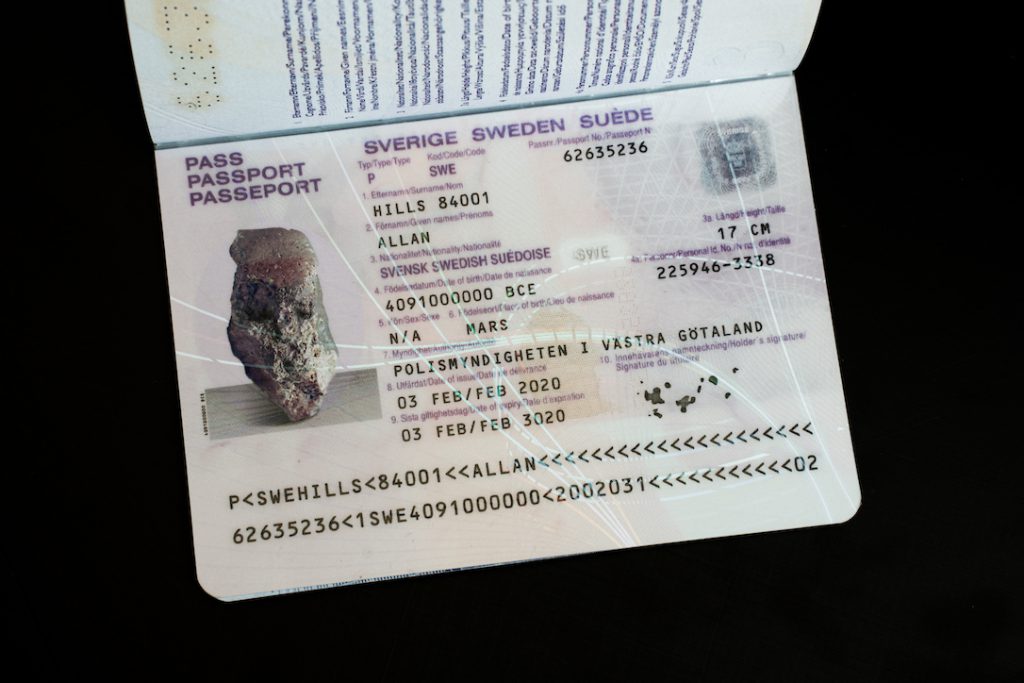

The meteorite’s passport, a Swedish one even, is yet another pointer to the absurdities of man-made systems of national borders and their enacting artefacts like passports. Even though the meteorite landed on a protected international continent, Antarctica, they felt it needed a passport, even though Antarctica might be closest to what they envision Mars to be. Was the EU passport a conscious choice? Do they touch on the #RefugeesWelcome, the #LeaveNoOneBehind, the #NoWallsNoBorders movements with what I consider a political statement? Can one feel a sense of belonging to a social group without such document? Does one get granted rights, agency, a narrative of dignity even without? It may only be a stone that gets discussed here but this well can be extended to pan-European and global debates around citizenship, migration and refugees/IDPs (internally displaced people).

Something that stuck out to me from their launch conversation was the statement on being a guardian for a natural being, whether a mountain, forest or else, and thinking holistically about that guardianship, trying to stand up for what is best for the object of guardianship. Well, as Våglund points out this object hosts a multitude of subjects, be that different matters on Mars or various animals, plants or else in a forest: “You cannot be kind to everything and everyone, as you cannot be kind to the rabbits and the foxes at the same time.” pointing at natural hierarchies and interdependencies. This leaves for a really enticing thought process on who benefits from whose decisions and in which contexts. This complexity is like to see unravelled and discussed in social movements and which to me is a key reason why various knowledge systems must act to complement one another.

DM: In their extensive study of social movements, Della Porta and Diani (2006:2) identify two larger social movements’ themes at the start of the millennium: your typical class movements’ themes but also themes such as gender equality or ecology that are more often associated with new social movements. Fidjeland and Våglund’s work could be categorized under the latter. Also, Della Porta and Diani highlight how “very misleading” associating expressions like “global justice movement” with unitary, homogeneous actors would be. This makes one wonder whether Fidjeland and Våglund’s movement – again, if this is what we want to call it – is at all connected to this wider social justice movement. They are after all explicit about Nonhuman Nonsense seeking to transmute our relationship to non-human, but what would you say is innovative about the way the experiment is disruptive?

NM: Yes, you are absolutely right to point out that thought on a global justice movement. I think that is what they would also point at with their guardianship approach. They would put people in the hot seat to suddenly really have to stand up to support what would be best for Mars, and Mars only. The rather homogenous team of Nonhuman Nonsense already stated that these guardians should be made up of diverse individuals from various philosophies, indigenous and other knowledge systems and work in unison on this guardianship to uphold Mars’ rights. I can imagine that this could serve as a great platform to show the complexity, near impossibility of a global justice movement in that dialogical subject-object dualistic interplay. That may be a disruptive consequence of their approach as the guardians are not yet selected and at work and it may well remain theoretical in nature. However, this thought process initiated by them is quite a subversive one as it is making me play through various possible outcomes. In a way I see it as an overarching umbrella for a plethora of social and ecological movements (if we want to separate the two here) to emerge from the discourse sparked here.

I wonder, (how) did it feel disruptive to you? Am I understanding correctly that you have identified their work as (part of) a movement with more certainty and clarity than maybe I have at this point?

DM: I often go back to Blumer’s (1969 quoted in Crossley 2002) definition of social movements as enterprises that derive their power from dissatisfaction with the current form of life and wishes and hope for a new system of living. It is true that Nonhuman Nonsense can, at first sight, seem to lack the “collective” but it may also be perceived an umbrella for various movements with overarching goals and objectives, as you rightly put it. Like I mentioned earlier, Della Porta and Diani (2006) warn against associating expressions like “global justice movement” with unitary, homogeneous actors. I agree with them that this would be misleading and believe such movements range from those that advocate for a world with no other borders than natural ones, a world where free movement is a human right to those that fight for governments and policymakers to truly commit to ecological sustainability. Both a world without countries and consumerism can seem utopian today but there are undoubtedly more projects such as Fidjeland and Våglund’s out there. So yes, whether utopian or dystopian, their work is linked to a wider movement or wider movements.

Between utopia and dystopia. Would you say that is how the project’s founders view the world, one where everything is simultaneously perfect and imperfect? Would you like to elaborate on this point?

NM: The struggles they touch upon, destruction of land with its bio- and geodiversity, conflict and migration, liberation movements, structural oppression and racism (or biocentricity as they may refer to it), the suppression of indigineous knowledge, capitalist exploitation of resources, hit too close to our home, Earth, for me to see their vision as utopian. They are so brutally aware of and pointing out these structural barriers of oppression that seem insurmountable so that a step to establish and sign the Universal Declaration of Martian Rights may be the last straw they hold onto. Have they given up hope on Earthlings already? Do we find redemption only by supporting a planetary ecosystem outside of our own? Do we have enough time to learn? They ask about which absences and presences matter and while we may get a chance to answer with compassion now, do we still get to turn around the wheel for human societies?

On Mars everything and everyone is born free. This ties in well with post-colonial excitement of the born-free generations after various former colonies gained independence. Do the same consequences await on Mars though? Too many repressive traits have been internalised and not yet unlearned so that societies may actually never start off as a blank canvas. If we now look at Mars as the ‘other’, can we really move away from biocentricity if mindsets such as Eurocentricity are still so prevalent (McEwan 2019, Said 1978)?

I guess what I am trying to articulate is that I cannot see how anyone can draw up utopian futures once exposed to our global, local and glocal struggles. So yes, while a sense of utopia may be carried through the project’s work or desired outcomes, it will always come with dystopian baggage of generational trauma.

And don’t we already see this happening on the side of the aggressor? Musk’s SpaceX colonial project to conquer and man Mars for the global elite to seek refuge on when our planet becomes inhabitable? Even without living matter it seems that once again the white man is portraying colonialism as a means of self-defense, the aggressor as the brave man protecting mankind (Harney, Moten, 2013). Adjacent to it all can we expect Martian development agencies to be set up next?

DM: We have already touched on the fact that Fidjeland and Våglund’s ambition is to tell “stories that open the public imaginary to futures that currently seem impossible”. What is the public imaginary? Do you think there is a public imaginary or many public imaginaries out there?

NM: See I have been struggling a bit with that sentence. Are we talking about imaginary futures? Or is there such a thing as a “public imaginary”? The latter to me would be something I could relate to the perception of sounds, colours and smells on the most rudimentary level. We may agree on a few characteristics that make it possible for us to discuss close to the same content (a high pitch, the colour fuchsia, a foul smell) but we can only really refer to our own perception of said content of debate. In a way this leaves a void, a vacuum, a space I could refer to the public imaginary. It is that space that in my understanding could be filled with speculative futures that allow us to break away from the status quo. However, just as sounds, colours and smells, we again cannot free ourselves from our own perception, but just be very intentional about our compassion, empathy, solidarity and attention. So yes, in a way there are multiple public imaginaries out there according to my understanding.

Is that term for you more related to the imaginary futures or to the public, to people as a whole?

And finally, if you consider this project of Planetary Personhood as the start of a social movement, what could you imagine the milestones to be, what would be your speculation of a possible consequence in the near future, if any?

DM: This is a good question, Nina. Just looking at the pandemic and the consequences it has had on all of our daily lives’ and thinking of how far we all were from imagining the world as it is today, I dare not venture into any speculations as to what the future holds. Uncertainty is what feels most certain in the future, both nearby and far away. I would say Fidjeland and Våglund’s initiative is a strong, important link in the larger chain that connects the public imaginaries they refer to. These may be manifolds, but they are multiple facets of one big picture, our common future on Earth, on Mars and beyond.

Thank you for this, Nina! I am sure you agree that the conversation raises more questions than answers and look forward to reading answers or more questions from our readers.

References:

Crossley, Nick. (2002). Making Sense of Social Movements. Philadelphia: Open University Press

Della Porta, Donatella and Diani, Mario. (2006). Social Movements – An Introduction. (2nd Ed.) Blackwell Publishing.

Eyben, Rosalind. (2014). International Aid and the Making of a Better World: Reflexive Practice. London: Routledge

Harney, Stefano & Moten, Fred. (2013). The Undercommons, Fugitive Planning & Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions

McEwan, Cheryl. (2019). Postcolonialism, Decoloniality and Development. 2nd ed., London: Routledge

Newcomb, Steven. (1995). “Perspectives: Healing, Restoration, and Rematriation.” News & Notes, pp. 3. Available online: http://ili.nativeweb.org/perspect.html

Tufte, Thomas. (2017). Communication and social change : a citizen perspective. Cambridge: Polity Press

Said, Edward W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.