I have addressed the issue of discrimination in fundraising in my last two posts, and I thought that it is important to address the issue since fundraising is an essential part of the aid development sector and consequently social change. The development sector as we all know is predominantly white led which implies that other races are less represented and less involved compared to their white peers. Serious issues in the aid sector have been exposed though social media, and as it seems the aid system is unfortunately similar to the colonial policy of control. The lack of inclusivity, structural racism, white superiority and social inequality are affecting the development and as a result social change in the recipient countries. In this post I will try to analyze how deep the racial bias goes, its global negative impact and how can development be redefined. One thing is sure the aid sector needs a major change.

The Aid´s design model

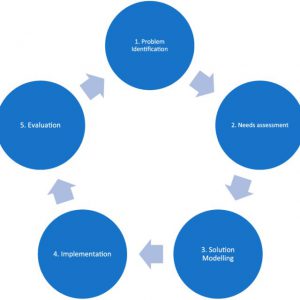

In order to understand the aid sector system, it is important to look at the way it is designed. Flint et al. (2018) describe the traditional project management cycle as the following:

It is noticed that there are numerous problems regarding this model designed to be “evidence-driven or goal oriented”. As a matter of fact, the model builds a relation donor/recipient based on differences “in terms of power and levels of engagement”. It is explained that the “problem-solving approach” is adapted to the expertise of foreign experts who have experience in fields such as engineering and management. This model puts on the sidelines the “users of aid” (defined as “individuals, organisations, groups, and governments who are affected by taxpayer and donor-funded aid and development pro- grammes, typically in developing and transitioning countries”). In fact, they are made “programme takers” while the experts are positioned as “programme makers”, even though “users of aid” are involved at certain levels in consultation and participation. The donors are in charge and impose their vision on the recipients. It is acknowledged that the international expertise is important but should be restructured in a better way (Flint et al, 2018, p.208-211)

” In terms of design, this is a system that is donor directed, expert devised, and expert implemented. Proponents of the model might argue that the percentage of national staff at implementing organ- isations has steadily increased over the past few years, but this does not detract from the fact that the aid users are rarely, if at all, meaningfully consulted. ” (Flint et al, 2018, p. 214)

For this reason, the local practitioners are left out. This model doesn’t take into consideration the value of the local staff and how beneficial it would be to include them from in the project design, making and implementation. Why is the western vision on local affairs better than the local one?

Structural racism and discrimination

Not only there is a power imbalance between the donors and the recipients but also there are signs of structural discrimination in the aid sector. The Peace Direct report (2021) reveal the presence of structural racism in the aid sector. The issue has been just recently acknowledged largely due to the movement” Black Lives Matters”. The global north aid sector practitioners are often perceived as more civilized than the non-white populations, they are experts and have skills while others lack experience and need “capacity building”, global north aid practitioners have better salaries and benefits, they know how to play the system and take advantage of their connection with donors. Also, they have the advantage of being “neutral” which reinforces the concept of the “white gaze” or “white savior”. ( Peace Direct, 2021, p.12)

Meaning the global north aid practitioners as outsiders get the responsibility to solve issues regarding local communities considered helpless and in need of the global north help.

Moreover, it has been noticed that the issue of racism and discrimination is even amplified if the local practitioners belong to marginalized groups; women, communities such as the LGBTQ, persons with disability or non-anglophone community to name a few. (Peace Direct, 2021,p. 15).

These compelling facts are signs of a system that favors and reinforces the white privilege in recipient countries and consequently negatively impact the very purpose of the aid sector. What can the outcomes of the aid sector possibly be about social change when the system itself defective?

Organizational segregation

Another important factor that explains the defective aid system model is the segregation in the aid department. Hor (2017, p.11-12) analyzes in depth the work relations between the international aid workers and the locals and come up with the concept of “us-ness” versus “them-ness”. International aid workers as in “us-ness” are said to form their own group within the organization as decision-makers. The locals are the “them-ness” meaning they form a separate group and are given less voice in the matters of the organization. Not only it is reported that local aid workers are barely consulted, even the local beneficiaries lack the opportunity to tell their own stories. For example, “J., an anonymous aid worker who also relishes in his professionalism, confesses that aid workers often only listen to the local beneficiary through ethnocentric lenses.” (p. 8)

The lack of diversity in boards meetings is mainly due to high standards. To be able to occupy a high position as expert or expat, the local staff need to meet the requirements that demand master degrees, many years of experience in the humanitarian field and other qualifications that make it very hard for someone who hasn’t studied or worked abroad. This form of hiring process is designed to keep the locals at a lower level while international aid workers will most likely be in charge.

However, one explanation to the requirement of master degree or higher educational degree is that” the aid industry required “masters degrees” and “expertise” in an attempt to domesticate one’s emotional anxiety through intellectual control. To understand this complex matter, it is important to mention international aid workers feel emotional and suffer of anxiety, sense of guilt, depression in the line of their work (Hor, 2017, p.14).

Nonetheless, it is reported that INGOs have designed complex administrative standards, some unachievable benchmarks in an effort to minimize risk, corruption or anything that could negatively impact the programme. Local practitioners are hardly seen as competent despite their experience. The language is also another way requirement that is set, locals aid staff are expected to know “good academic English”, have some references and be able to understand their” ever-expanding list of sector-specific jargon”. The local practitioners don’t understand the reasons behind some requirements. The aid sector however does create opportunities for the locals but fail to include them in the process making of a project, meaning the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation (Hor, 2017, p.25)

Due to the obvious inequality in the aid sector, it is understandable that some feel like the aid system is a continuation of colonial dynamics.

The distant practitioner and white gaze

Aid practitioners are programmed to be more technical, specifically to cope with the emotional aspect of the aid sector. Local beneficiaries would be reduced to numbers not humans (p.15). The dehumanization of local subjects can build a wall between aid practitioners and protect them from emotional distress and some even prefer to work behind the desk for that very same reason. This concept of dehumanization can also explain the distance that international aid practitioners keep while working in recipient countries, also refers as the “distant suffering stranger” (Hor, 2017, p.2). This neutrality is viewed as effective and instrumental but in fact reinforces the white savior complex (Peace direct 2021, p-17-18).

In this case, the white practitioner has the luxury to not stay neutral in the local context while others simply can’t since they are local and are directly connected to the local surroundings. It also implies that the white practitioner’s expertise is questionable in local social issues that local practitioners are aware of. But since they are hardly consulted, one might wonder on what do white experts base their solution modelling on?

Furthermore, the white gaze or “imperial gaze” is predominant in the aid sector. As previous stated, the aid system is not only predominantly white, but has issues with power inequality, racism, mistrust, and discrimination. Local practitioners feel that they are considered and are treated inferior due to their race. Local women feel have experienced the white gaze, mentioning that international aid workers have stereotypes and for example think that Muslim women have zero control in their lives or are submissive, which is a wrong and unprofessional way of viewing Muslim women. The aid system is in fact build on patriarchy, a system that excludes women in general, non-white women are not only discriminated as women but also as non-white. This results in gender-race based discrimination (Peace Direct, 2021, p. 16-18).

” There is a notion that aid workers cannot be racist because they sacrifice their lives to help brown and black people in Africa. Because of their assumed self-sacrificing and inherently benevolent work, white development workers are taken as ‘good’ and ‘trustworthy’. ” (Peace direct, 2021, p.18).

#aidtoo movement

The Oxfam scandal in Haiti and Chad in 2006 and 2018 revealed that top Oxfam staff had paid survivors for sex, some even underaged and has hired prostitutes (BBC, 2018). The UN sex scandal denounced the sexual abuse of children by UN peacekeepers. Children were sexually exploited in return for soldiers’ rations. Not only are the locals in recipient countries are subjected to sexual assault or exploitation but the female aid worker as well.

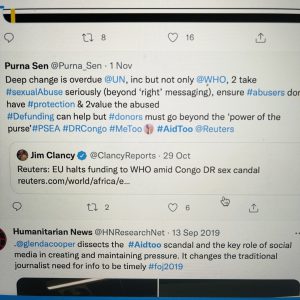

On twitter #aidtoo is trending and involving professionals all around the world, many demand investigations and justice. Apparently once scandals are made public, the organizations chose to fire the guilty ones and do some damage control. With the help of social media, the public demand change within the system. Professionals are informing the public on the latest news and encouraging social activism ( Twitter, 2021)

Denkus (2019) stresses how the #aidtoo and #metoo have led to a “broader debate” in this digital era. Activists are connecting around the world, and physical boundaries between organizations are no longer an obstacle. Globalization and technology are giving a voice to people and creating a new dialogue.

Fundraising

In my previous post, I have analyzed racial bias in fundraising and how local practitioners are expressing their frustration and advocating for change. Fundraising is described to be a field in which donors, board members and other executive directors have a fundraising relationship. People of color are unfortunately viewed as outsiders. This disadvantage is due to the lack of diversity, equity and inclusion. Non-white professionals are not encouraged, consulted and are not even “qualified” for certain positions. Fundraising being an essential part of the non-profit organization, favors the white professional and mistrusts the non-white counterpart (Burton, 2020).

One local practitioner explains that “So this funding comes with ‘Donor Templates’ which are tools, tailored to what the donor needs, not what the communities or beneficiaries need.” (p.28)

Non-white professionals are now speaking up and are raising awareness through social media. Local practitioners want to have a seat at the table and be involved in the decision-making process. Local organizations want to be able to get funds without being racially discriminated.

Is decolonizing the aid sector even possible?

” When it comes to patterns from colonial history being replicated, complicity of international actors in reproducing colonial hierarchies, and the presence of ‘white/imperial gaze’ – just consider the dominance of white voices in academic and policy literature on and in humanitarianism, development and peacebuilding.” (Peace Direct, 2021, p.32)

Denskus (2019) is discussing the same point by stating that there is a benefit in decolonizing the academy and mentions different ways of curating development. Local aid workers, journalists, young writers, activists from the global South should be given a voice. Aid workers around the world should engage in open discussions and change the traditional narratives. In addition, development challenges should be exposed and handled. Social media is introducing new ways of communication; podcasts, videos, tweets are great ways of engaging the public. Furthermore, there are new digital media platforms such Teds Talk and new cultural trends that include local movies, music, guest lectures, or artistic projects. Most importantly that teaching materials at the university are updated.

Others suggest for example that the global north practitioners reevaluate their aid system, relationships with the local practitioners, their language, acknowledge the existing challenges, give funds courageously, create space for change, invest in the local research and recruit differently (Peace Direct, 2021, p. 38-41).

It seems that social media platforms are starting to have an impact on the traditional aid system. Scandals or other challenges are now being exposed, even though the consequences are still unconclusive. Most local aid practitioners choose to tell their stories anonymously, raising the question of fear of repercussions. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the aid sector despite its challenges, is assisting communities in need around the world. The challenges and issues discussed shouldn’t imply that work and commitment of the global north practitioners is all ill-intentioned. However, it is important to highlight the issues that affect recipient countries in order for change to ever happen.

Concluding reflections

My blog content has been focusing on racial bias in fundraising from the perspective of local practitioners. This aspect of the aid sector has been published on BBC, blogs, and other platforms and opened a discussion on why the local non-profit organizations are struggling to get funds compared to their white counterparts. CSOs have had no other explanation than racism and discrimination. It wasn’t about their qualifications or legitimacy; the rejection was based on race. It is a complicated and yet shocking fact that can make someone requestion the whole aid sector agenda or goals. Why help people you don’t value as equals or simply trust? If you do feel pity for those communities and still want to help, could it be that the actions have a personal motive? Self-gratification? Or the need to be a hero? No wonder the aid sector needs to reevaluate and adopt a different mindset. Not to mention that the global north are democratic countries that claim to have equality, respect for human rights, no discrimination or racism, come to the recipient countries to teach them about democracy and social justice while they are not reflecting those values within their own organization. That’s hypocritical to say the least.

This exercise has been a challenge for me to be honest. I am not using social media in my line of work, and it is rare that I post anything on Facebook, Instagram, or twitter. The blog has pushed me to learn a lot about the power of social media, how people react and interact to different stories and how the process can open new discussions. Since I am not used to write freely in a “blog manner”, it has been also hard to not refer to academic references. Overall, the exercise has been a good way to be introduced to the blogsphere and I know that this new knowledge will be needed in the future.

Reference list

Burton, B.S.(2020). The issue of fundraising in the fundraising profession. AFP. https://afpglobal.org/issue-racism-fundraising-profession

Denskus, T. (2019, September 17). Blogging and curation content as strategies to diversify discussions and communicate development differently. Aidnography. https://aidnography.blogspot.com/2019/12/blogging-curating-globaldev-content-diversify-communicate-development-differently.html

Flint, A.& Natrup & M.Z. (2018). Aid and development by design: local solutions to local problems. Development in practice. 29 (2), 208-219, DOI: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1543388

Hor, A.J. (2017). Searching for Redemption: Distancing Narratives in the Everyday Emotional Lives of Aid Workers. https://wpmu.mah.se/nmict181group2/files/2018/03/SearchingforRedemption-DistancingNarrativesintheEverydayEmotionalLivesofAidWorkers-24Mar2017.pdf

Mangan, L. (2018). The UN sex abuse review: careful, dignified and grueling. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/aug/01/the-un-sex-abuse-scandal-tv-review

Oxfam Haiti allegations: How the scandal unfolded. (2018). BBC News. Retrieved November 1st, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43112200

Peace Direct (2021): Time to decolonize Aid-insights and lessons from a global consultation. London: Peace Direct.https://www.peacedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/PD-Decolonising-Aid_Second-Edition.pdf