In June 2018, the No White Saviors account launched on Instagram. An initiative borne out of a frustration by a small group of professionals who were tired of “white saviors” in Uganda. In a little over a year, the account gained 200 000 followers, engaging thousands of African practitioners in digital activism. Today they have nearly a million followers. The movement is rapidly emerging and the group themselves describe their purpose as “dedicated to revealing African people as the heroes of our own stories. “ (No White Saviors website, 2021).

In June 2018, the No White Saviors account launched on Instagram. An initiative borne out of a frustration by a small group of professionals who were tired of “white saviors” in Uganda. In a little over a year, the account gained 200 000 followers, engaging thousands of African practitioners in digital activism. Today they have nearly a million followers. The movement is rapidly emerging and the group themselves describe their purpose as “dedicated to revealing African people as the heroes of our own stories. “ (No White Saviors website, 2021).

Two years later, I discovered this account, when a Swedish development news site wrote about the initiative. As a development practitioner within the communication field, I felt that their content challenged me, gave me new perspectives and knowledge on postcolonialism in practice, and how storytelling from media and development actors can cause a lot of damage and harm, without intention, but basically because lack of awareness and ignorance of power structures from the one sharing the story.

During six weeks of this blog project, I had, togheter with the group of students I have been part of, the opportunity to learn more about and discuss how ICT4D relates to communicating development from a postcolonial perspective. I have shared posts on why we need to, and how we can develop new narratives in digital times.

ICT bring the world closer, but will it unify us or draw us further apart?

No White Saviors is a great example on how digital information communication technology (ICT) have brought someone from an internet café in Uganda to the same conversation as me, in my home office in a city in Sweden. Digital ICT can be defined as “any entity that processes or communicates digital data: smartphones, laptops, computer software, apps, the Internet” (Heeks, 2017, p9). The development enables us to meet in new arenas and exchange ideas and experiences. It also challenges us, because we need to consider that our audiences, when sharing thoughts and statements, are not just copies of ourselves. It can be a person who lives in a different context and has other perspectives on things. The global migration flows also means that the classic geographic division between donors in the north and recipients in the south has changed.

This issue is raised by Ademolu and Warrington (2019), where they address that many international development studies focuses on the different ways in which visual representations of poverty affect and shape public perceptions and knowledge. However, they tend to imagine western audiences of NGO communications as a homogenously white community of people. An assumption that ignores the variety and complexities within audiences, and don’t reflect the differentiated ways in which audiences relates to NGO representations.

This is a fact that we no longer can ignore, when working with communicating development in a digital setting. According to Shringarpure (2020), it is clear how digital humanitarianism offers new visions and approaches to improve humanitarian work. However, she also claims how it emphasizes the divide between those doing work on the ground and those who choose to contribute from distance. It not only transforms crises into everyday virtual realities but also fosters the distance between the savior and the saved by demanding that individuals click, like, tweet, share and donate. This, she argues, results in the emerge of a Digital Savior Complex, that increases already existing colonial hierarchies between the savior and the saved.

New voices arise and bring tools and an opportunity for shared standards

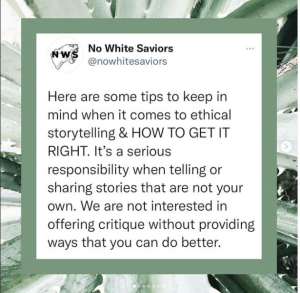

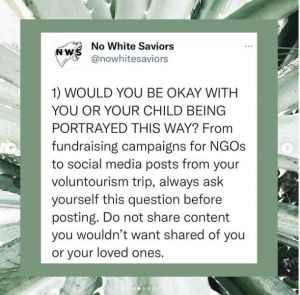

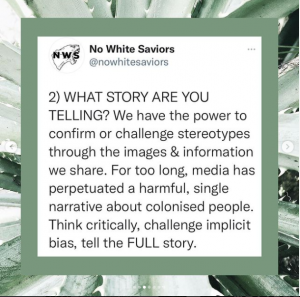

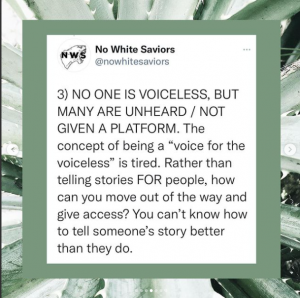

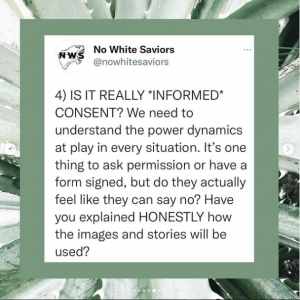

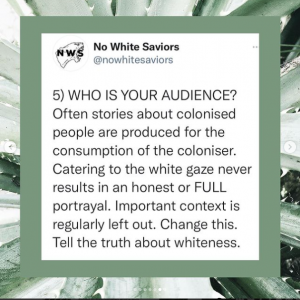

Along with the emerging digital savior complex we see that groups raise their voices and advocate for a change- towards a strive for ethical storytelling and equality. No White Saviors, who was previously mentioned, raised in a post the 16th of July 2021 at their Instagram account, thoughts on the importance of ethical storytelling, and tools for NGOs to apply:

As mentioned in a previous blog post, Dignified Storytelling, is another project whose aim is to advocate for a new standard of storytelling. The Principles of Dignified Storytelling have been agreed upon by a group of stakeholders from UN agencies, INGOs, local NGOs and civil society. They are concluded as following: https://dignifiedstorytelling.com/the-principles/

Can guidelines or new principles like the ones shown above eliminate the postcolonial oppression that is seen in a lot of campaigns and communication from development agents and media? For sure, it will not alone be enough, but a shared understanding of why we need to work differently and what aspects that needs to be taken into account can help us to improve.

What difference can participatory methods do for storytelling?

An example of how storytelling can look in practice that is born out of a participatory method is a digital art exhibition that was arranged by the INGO Oxfam International. In August 2020, it was three years since a military attack in Myanmar, which resulted in that more than 700,000 Rohingya people fled to Bangladesh. To bring attention to this moment, Oxfam asked Rohingya artists in Bangladesh and Myanmar to share artworks reflecting on their own experiences and dreams for the future. The artists reflect upon past hardships and trauma, daily joys, and their hopes for the future in their artworks. By sharing the local artists work in Oxfam’s global platforms, digital audiences globally could take part of the experiences of the refugees without the stories being edited and created by a campaign producer at Oxfam.

One of the artworks from the exhibition is the painting “Life of Rohingya Women” by Enayet Khan. Enayet share in an interview with Oxfam that he spends his days painting inside his shelter at the Nayapara refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The camps that are home to Rohingya refugees who fled the violence in Myanmar. Early on, Enayet has experienced many difficult traumas, and he says that art has offered a way for him to reflect on and express what he and his community experienced. His paintings illustrate a broad range of experiences related to the military operations in Myanmar and the Rohingya community’s escape to Bangladesh.

“Life of Rohingya Women” by Enayet Khan

Bentley, Nemer and Vannini (2019), is a group of researchers that argue for the benefits of using participatory methods. In studies, participatory photography has been used for different reasons such as to solve urban design problems, to generate insight into the lives and cultural identities of migrated groups in new settings, and to understand risk behavior among certain groups. According to the results from these studies, the use of photographs to tell stories of practices and experiences could help to develop specific contextual awareness, especially when many cultural factors are difficult to express. Another benefit of visual methods relevant to critical ICT engagement is inclusivity. Visual methods enable even the most marginalized communities to communicate their thoughts and explain their ideas to researchers.

Shringarpure (2020), also share the importance of not assuming that poor people, especially those living in the Global South, don’t have critical perspectives. She discusses that we tend to see people living in poverty as people who can only present us with their own individual “stories” of lived experiences, as opposed to individuals who have critical opinions about how they are represented. A participatory method can enable a broader perspective to be portrayed than just the personal storytelling we often see take place.

The author and development practitioner Rosalind Eyben reflects in her book “International Aid and the Making of a Better World: Reflexive Practice” the importance of a relational approach along with the participatory one, addressing the importance of creating friendship and relationships between the development practitioners and the “beneficiaries”. She also emphasizes the need for reflexive practice. Eyben here understands reflexive practice as “a deliberate process of becoming unsettled about what is normal, recognizing that there are concurrent realities and that how I personally understand and act in the world is shaped by the interplay of history, power and relationships” (Eyben, 2014, p45).

How do we embrace the ethical principles in development organizations?

New ethical standards for storytelling, inclusive and participatory methods, and reflexive practice sound great, why don’t we apply it immediately?

According to the report “The people in the pictures” (2017, p5), from Save the Children, internal research carried out by them demonstrates that audiences made their own judgments on whether someone was ‘in need’ and that surprisingly small indications of resilience could stop them donating, for example: “They look quite well fed. They’re not starving enough.” Further they describe that Save the Children, aware of this dilemma, is trying out multiple ways of telling stories, and audience responses to those. At the same time as they have obligated to avoid images that homogenize, falsify, fuel prejudice or foster a sense of Northern superiority. They have also produced guidelines such as the Code of Conduct on Images and Message.

This unfortunately show that even if the organizations want to change, the question is not all about how to change the narrative, but to a large extent a financial question. Should we continue to rely on private donations made by people feeling pity, or develop new ways of collaborations that will be birthed out a willingness to create long lasting change? This transformation will take time and cannot change over a night. Unfortunately, shared standards will never be enough, if the dependence on donations from people wanting to be portrayed like heroes will continue.

Concluding reflections on developing new narratives in digital times

What I have tried to, together with my peers, to address in this and other posts during this blog project is that we need the voices who question the practices of today and voices that develops new tools that help organizations to improve. New media and ICT give us new instruments to use for more inclusive communication, like the development of podcasts, and digital participatory exhibitions mentioned in the posts. But if the situation should change for real, it is also a question about the principles of funding and who one relies on for money.

This blog project has however, foremost, given me, an opportunity for self-reflexive practice. To read about this issue, investigate, listen to different voices and perspectives, and write about what I daily work with but don’t have time to reflect on during work hours, has been important and made me reflect in new ways.

It has also reminded me on how the internet and social platforms, like this one, connects and bring different groups of people together. People, that I have very different relationships to, family, neighbors, former and present colleagues, friends from many different countries and classmates and teachers from my university. These are all people I appreciate to interact with, but in the real world, compared to the digital one, I think most people adapt their communication depending on who the person is and what kind of relationship one has. In a blog like this, suddenly all people in my professional and private network share the same content from me, just like the issue that organizations face. So how do I relate to that? No easy answer other than that it forces me to express me in a way where I try to not make anyone feel unfairly accused by my argumentation. But reflexive practices also teach us that we never can be perfect, but by realizing our limitations we can try to listen more and be humble of that we sometimes make mistakes and can do better by gaining new knowledge from people around us.

Word count: 1927

Sources:

- Ademolu, E. & Warrington, S. 2019: Who Gets to Talk About NGO Images of Global Poverty? Photography and Culture, August.

- Bentley, C.M., Nemer, D. & Vannini, S. 2019: “When words become unclear”: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D, AI & Society, 34, 477–493.

- Eyben, Rosalind (2014) International Aid and the Making of a Better World: Reflexive Practice. Oxon: Routledge.

- Heeks, Richard. 2017: Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D), Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shringarpure, B. 2020: Africa and the Digital Savior Complex, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32:2, 178-194.

Internet sources:

- Dignified Storytelling. (2021) Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://dignifiedstorytelling.com/the-principles/

- No White Saviors Instagram account. (2021) Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/nowhitesaviors/

- No White Saviors Post on Ethical Storytelling. (2021) Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/p/CRZgI5EsdSm/

- No White Saviors Website. (2021) Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://nowhitesaviors.org/who-we-are/story/

- Oxfam International. (2021). Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://www.oxfam.org/en/rohingya-realities-rohingya-futures-winners-oxfams-2020-art-competition

- Oxfam International, “Life of Rohingya Women.” (2021) Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://oxfam.medium.com/rohingya-voices-the-painter-of-nayapara-refugee-camp-7e6f3bb1c5b6

- Save the Children report. (2017) The people in the pictures. Retrieved 6 November 2021, from https://dignifiedstorytelling.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/the_people_in_the_pictures.pdf