In this thread I would like to discuss on a deeper level three topics that particularly caught my interest, in the broader discourse of development decolonization and coherent ICT4D participatory practises, and that I think are of fundamental importance:

– Risks & Solutions of Digital Aid (introduced here)

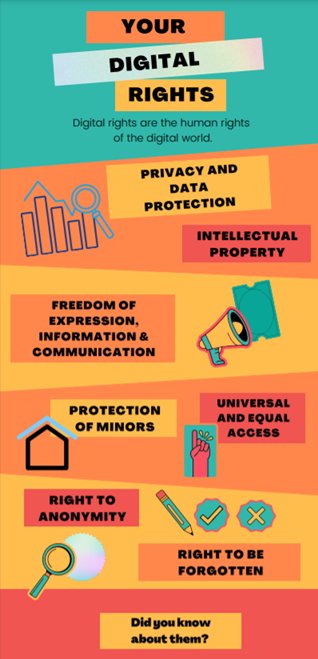

– Digital Dignity: How do we ensure digital rights? (I discussed about it here and here)

– Media representations & dignified storytelling

When we talk about “international development” we have to discuss digital media and communication approaches of every actor and sector, as international development relies greatly on digital communication. The implementation of digital solutions provides huge opportunities to enhance the performance of humanitarian practices and reinforces peacebuilding and protest activities.

If we talk about the most commonly used tools, as messaging apps grow in popularity, their usage in emergencies is also on the rise and could play a crucial role in the future (Lunt 2017). Affected communities can keep in touch with each other, have access to updated information and connect with humanitarians to report on emergency situations. When a disaster occurs, access to right information is not always easy, but it is critical to provide fast, diversified, safe and sustainable communication streams that will help organizations make quicker and pondered decisions that can save lives. (Heeks. 2017).

The implementation of advanced information systems, such as humanitarian apps, contributes to tackling a wide range of problems (Lunt 2017). For example, 4W maps were developed to provide information for humanitarian assistance planning, covering critical questions, such as who is doing what, where, and when. Crisis mapping is also one common means of digital humanitarianism. Drone application instead permits mapping, delivering essential items to remote locations, monitoring environmental changes and damage evaluations (Fondation Suisse de Déminage 2016).

RISKS

At the Wilton Park conference the implications of digital technology for individuals affected by armed conflict were discussed, identifying five major existing problems:

- Dual-use technology: Facial recognition software, drones, biometric and digital identity systems, crisis mapping tools and satellite imagery, although initially used for good, may also do a lot of harm on crisis-affected populations that can become targets and cause issues, such as data protection.

- Third-party service providers: It highlights the question of ownership and consent over information and data that is being shared. Especially when the third-party is a commercial entity that clearly benefits from the exploitation of this data.

- Humanitarian Data Incidents: Events involving the management of data that have caused harm or have the potential to cause harm to crisis-affected populations, organizations on the field and other individuals or groups.·

- Humanitarian and Civilian Data Targeting by Military Actors

- Handling of requests for access to biometric data by state authorities.

While digital solutions provide the capabilities to respond to crises in a better way, if mismanaged, these same technologies risk exposing users to violations of their rights (Hill 2018), causing problems related to data protection, privacy, misinformation, propaganda, data interception, or unauthorized access.

Unfortunately, humanitarian organizations do not have appropriate standards or internationally agreed and approved ethical digital regulations, that in combination with people’s living conditions, culture, inequalities can cause serious obstacles in facilitating humanitarian support. The biggest issue is the fact that legislation around the protection of metadata and data is not uniform worldwide, and the places where humanitarian facilities operate tend to be under-legislated (Bouffet and Marelli 2018). This gap can be used to violate human rights, freedoms, and create threats to lifes of humanitarians, volunteers, or affected communities.

MAKE DIGITAL RIGHTS REAL

Protecting personal data means protecting life: there is an urgent need to identify the ways to mitigate risks in humanitarian action digitalization. Some attempts to protect personal data and information apps are performed by their developers, as of Telegram, even prior to the implementation of the GDPR in Europe. The International Committee of the Red Cross also deals with the issue of metadata protection in the framework of humanitarian action. (ICRC and Privacy International 2018)

All parties involved in humanitarian action should understand the need to prevent the leakage of personal data and violations of privacy. Unfortunately, much depends on the decision-makers, CSR initiatives and policies within the companies and appropriate support from the government. According to Kaspersen and Lindsey-Curtet, it is essential to provide “proactive discussion on global standards for collecting, sharing and storing data in times of crisis – and a zero-tolerance for attempts to penetrate these organizations to gain insights into people at their most vulnerable”.

The Digital Geneva Convention would safeguard civilians around the world from state-led or state-sanctioned cyberattacks in any moment. (Microsoft 2017). Thus, this initiative is an urgent call to action to update and adapt rights and obligations to the current dynamic realities, ensuring digital dignity and protection for all parties involved. World government leaders, NGOs, humanitarian organizations should incorporate cyber threats into legal, social, and political frameworks.

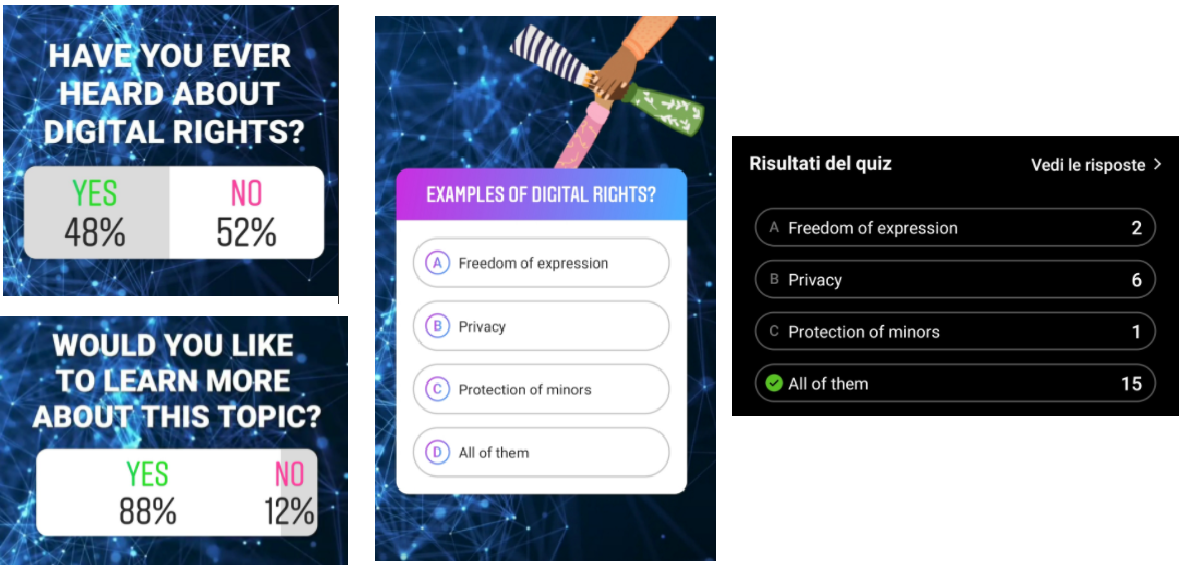

For the Digital Freedom Fund, it is fundamental to “make digital rights real” – for them to be tangible and relevant to everyone in society, not just to a privileged few. They have to be firmly situated in broader social justice. Hopefully, this will help to realise more ambitious goals, like defunding surveillance tech that targets racialised communities and re-directing resources to communities. It was found that what are considered top priorities are different than the practical issues that marginalised groups face on a daily basis (ex: digital access), and that some digital rights organisations approach systemic injustices from a merely technical perspective, rather than considering them harms that intersect with other human rights violations.

The Human Rights Watch proposes three suggestions to protect human rights in the digital sphere:

– Creation of a “special rapporteur” for the right to privacy at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva.

– Contribute to Development of Multi-Stakeholder Internet Governance: Being tested by global connectivity, some governments (ex: China), increasingly endorse a concept of Internet sovereignty. The multi-stakeholder model for Internet governance must be protected and strengthened.

– Human Rights Protection should be a National Security Priority: it is needed to solidify the international understanding that protection of human rights and adherence to the rule of law in the digital realm are essential to the protection of national, global security and human rights, rather than antithetical to it. Digital attacks on human rights activists and civil society actors have become the way of repressive governments to undermine human rights work.

Digital risks are an integral part of our lives, as we cannot ignore the new opportunities that enhance the performance of humanitarian action, but we should create an environment that is friendly to human rights, freedoms, and dignity.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS

Since the 20th century, the media has been using images of violence, suffering and trauma to engage with the public to generate emotion and demand that something needs to be done to alleviate suffering of those in crisis (Neuman, 2017). The power of humanitarian imagery is used in order to create a “community of interest” as a form of solidarity, with the hope that it would generate a larger public interest and subsequently, a CNN effect. According to Lobb and Mock (2007), during humanitarian response efforts, the mass media serves as the primary informational intermediary, informing donors, and policy-makers as well as the non-affected public: “disaster and crisis response often is hampered by poor communication.” . In fact, media coverage and its intensity on crises has very little, if any, to do with humanitarian needs and it is decided based on other aspects such as “geographic proximity to Western countries or elites, costs, logistics, legal impediments, risk to journalists, relevance to national interest, eye-catching story and news attention cycles”.

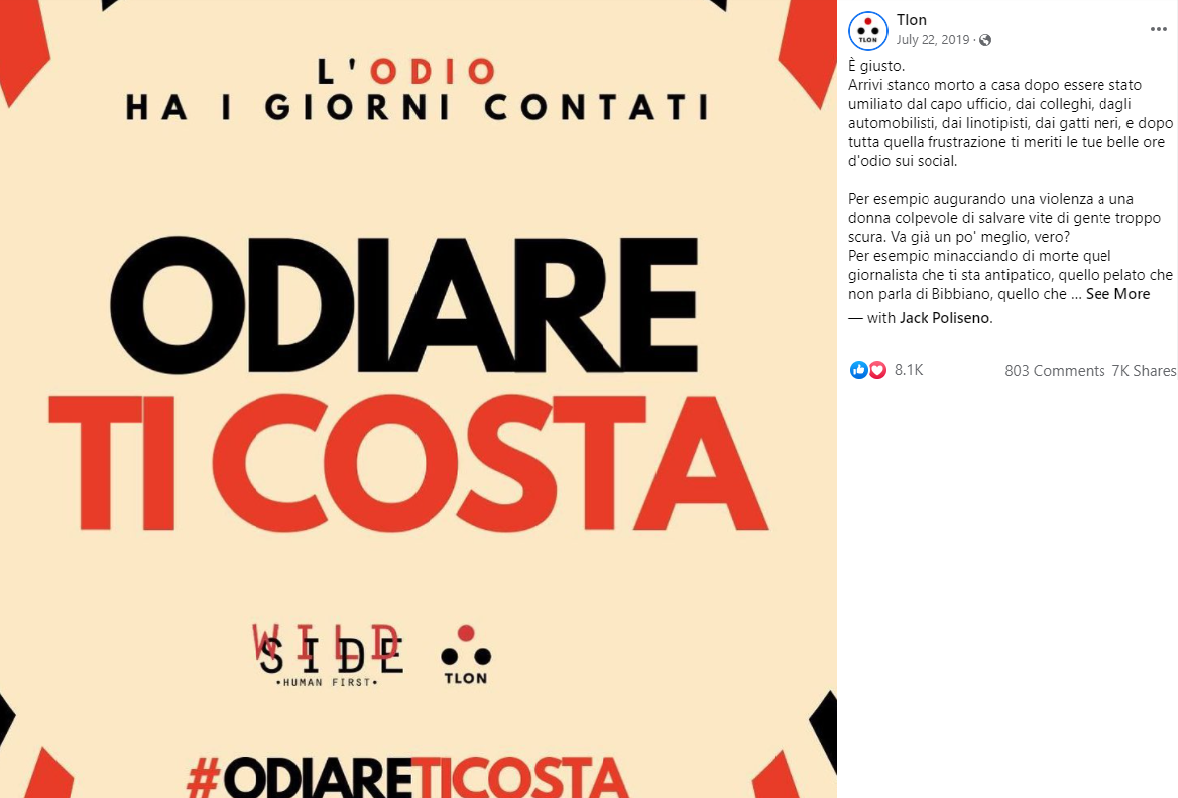

The overwhelming media coverage and the trap of imagery can do more harm than good. Media has the power to generate funding, but the selective nature of media’s interest affects the sustainability of the resources, and lots of needy emergencies are not covered. NGOs are also guilty of using negative images: although they can instill compassion and will to donate, audiences could also feel manipulated through the feelings of guilt and cause them to be resistant (Orgad and Vella 2012), can spark a desire for revenge and campaigns can also lead to compassion fatigue, leading the audience to fail to respond. Often, there is less coverage in certain areas of conflict due to accessibility and safety reasons and the media would rely on alternative sources such as the NGOs on the ground. In return, NGOs could get good publicity and create public pressure and challenge official sources. Still, the media lacks critical analytical assessment of information, which leads to error in judgement and inappropriate response to aid. The amount of effort and resources mobilised by the sensationalism could be coordinated better, channelled to aid crises which are neglected.

In order to mobilise appropriate humanitarian response, humanitarian NGOs and agencies, officials and the media need to work together in order to thoroughly consider the social imaginaries of the groups of people they are sending aid to and prevent misconception of information from being broadcasted and educating the public so to achieve a better understanding of the communities.

DIGNIFIED STORYTELLING

As I stated, it is important to avoid poverty porn not just for directing the aid properly, but also for ethical reasons, to ensure a dignified and empowering storytelling for the communities.

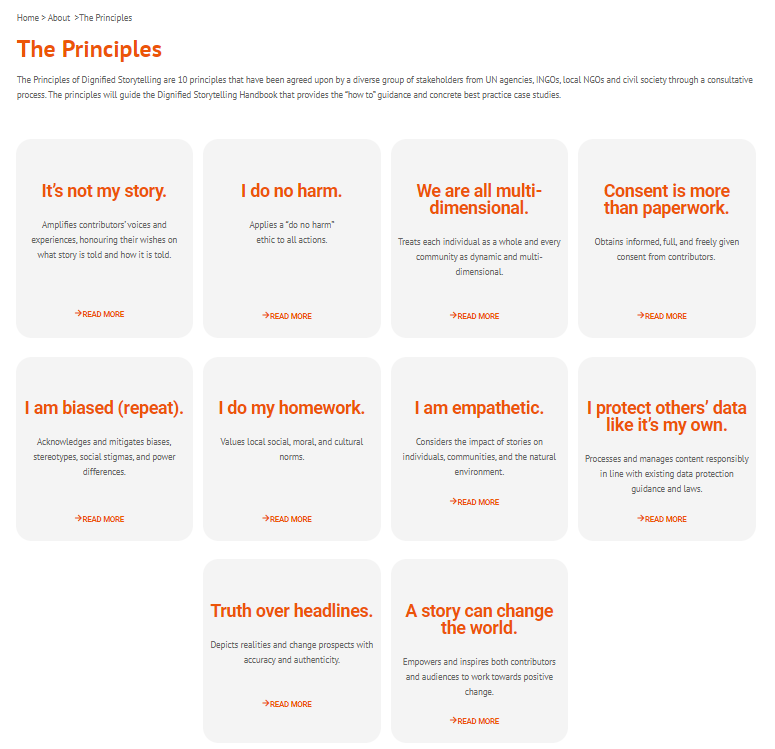

So how do you create a powerful message which both respects the subject?For Mr Echwalu, a refugee worker in Uganda, the answer is simple ” humanising people. An ideal way is to tell stories – positive stories about ambitions. Yes,- they were in a bad situation-, but I would always use the voices of the people. I think there is a media landscape: bad news is more interesting than good news, the challenge is to tell the true story, with dignity and respect.” For example the 2017 Golden Radiator Award went to Batman, by War Child Holland, with the jury describing it as “powerful” and as “effective humanitarian crisis imagery“. I would like to stress the importance of the “Principles of Dignified Storytelling” and The Dignified Storytelling Forum that will take place at Dubai’s EXPO, that promises to expand an enriching discussion about what really is dignified representation.

In order to end poverty porn we have to be careful about 3 corcerns:

- There’s something fundamentally wrong with the equation “more fundraising = less poverty”, as only a fraction of humanitarian aid goes through local organisations.

- It’s time to stop interacting with audiences in a transactional way, and make them join the change, not just “click and donate”

- Reinforcing narrative frames that center whiteness and wealth is dangerous, irresponsible, and unacceptable.

Even though they may carry fundings, we should avoid PR-ized stories:

“Despite her good intentions, the focus of the PR-ised story is clearly the celebrity herself, as a corporate brand, while the people she purports to save are pushed outside the frame. They don’t have much to say about (…) an inherently unequal, competitive & unjust system-perhaps because their privileged Western, white, middle class backgrounds have not adequately prepared them for the realities of intersectional race & class based oppression”

Celebrities firstly get to decide which causes should receive the attention, they take away the focus from the recipients of aid but also from successful local initiatives. We can say that white saviorism is often connected to celebrity humanitarianism, and it is crucial to aim for for helping communities help themselves instead of trapping them in an eternal need of foreign aid.

I think that it also crucial that practitioners keep ironically interrogating themselves about field work through memes, satyrical videos and parodies as in #HumanitarianStarWars. Irony is often a double-edged sword, but if used properly, it can amplify exponentially the power of criticism.

SOLUTIONS

We need to decolize aid work, as Kenyan writer and development consultant Ciku Kimeria says: “the development sector today is still full of examples of paternalistic attitudes from the West: average Western undergraduate educated people get to chair meetings of local experts with decades of experience” .We understood that “Technology as an abstract concept functions as a white mythology”, and that AI, the digital realm and the whole development sector are intrinsically racists. (Denskus T. ,2020)

One solution is to foster more and more participatory practise. The book by Buskens and Webb (2009) had three emancipatory themes: agentic use, critical voice, and personal and social transformation. It is important to discuss situational awareness of the role, reflexivity and power over the use or design of ICT. Receivers are not just recipients but participants in the decision making process, they retake control over the media coverage of the crises they face, instead of waiting for others to reach them, increasing community engagement. Participatory methods have often been perceived as a means to address power inequalities within technology design in developing countries.

At least as much attention needs to be paid to issues of inequality as to the use of ICTs for economic growth. For example, it is crucial to address the gender problem in the digital sphere: a significant gender gap in mobile phone ownership and usage exposes women to the risk of being left behind and it would affect the possibilities to be rescued from dangerous situations and to express the rights to life, liberty, and security of a person, as it is stated in the UDHR (1948). Mobile operators, software developers, humanitarian facilities, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can work together to promote policies and initiatives aimed to reduce the cost of phones and digital literacy.

To sum up, there are different steps that can be taken, including: fostering digital literacy, strengthening data protection practices and creating the right safeguards for the adoption of digital technologies, adopting suitable humanitarian policies, ensuring humanitarians continue to put people at the centre of their work.

In a world that relies and manages policies and commercial strategies on the usage of data, it is important to secure proper legislation regarding our daily communication privacy. In the Global South data extraction is unfortunately expected to become a booming business, “Mining” people for data is reminiscent of the colonizer attitude that declares humans as raw material.” (Birhane A.)

We should narrow the digital divide but it is needed to improve the knowledge of affected people and aid workers on the use of new technologies, to ensure the most secure and ethical use of digital devices. The continuous coverage of real problems faced by humanitarian missions, as well as a joint search for solutions should be always sought after. It is crucial to identify ways for covering the humanitarian principles such as humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence in the era of digitalization.

During this blogging experience, I found interesting to read about, and discuss the whole spectrum of reflective ICT4D practises, decolonization of development, datafication and digital rights (all so pressing, actual and critical topics!), and to explore new communicative methods and techniques. It was engaging for me to post content on my social media platforms and analyze the responses and to open threads linking different inspiring sources taken from my daily experience. What I would do differently next time is that I would experiment more with podcasts or videos, that I didn’t feel comfortable using this time. I think that even recording our online sessions and discussions would have been an inspiring documentation on how to create a blog from scratch. It was inspiring to collaborate with my colleagues and build together such a crucial and urgent discussion. I really enjoyed the collaborative approach of this examination, reading and engaging with blog posts permitted to reflect and to learn a lot while interacting with very knowledgeable people. Everybody has been very responsive and helpful, and I really appreciated having the possibility to discuss and e-meet other fellow students, as in online learning the socializing opportunity is not always easy to grasp. Thank you for your precious support and enthusiasm!

SOURCES:

- Akhmatova D.-M., Akhmatova M.-S. (2020), Promoting digital humanitarian action in protecting human rights: hope or hype, retrieved from: https://jhumanitarianaction.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41018-020-00076-2

- Bentley C.M., Nemer D. & Vannini S (2017), “When words become unclear”: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D, retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00146-017-0762-z#ref-CR7

- Birhane A.(2019) The Algorithmic Colonization of Africa, retrieved from: https://reallifemag.com/the-algorithmic-colonization-of-africa/

- Bouffet T, Marelli M (2018) The price of virtual proximity: how humanitarian organizations’ digital trails can put people at risk, retrieved from: https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2018/12/07/price-virtual-proximity-how-humanitarian-organizations-digital-trails-put-people-risk/.

- Cave S., Dihal K. (2020) The Whiteness of AI, retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13347-020-00415-6

- Chonka P. (2019), The Empire Tweets Back? #HumanitarianStarWars and Memetic Self-Critique in the Aid Industry, retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2056305119888655

- Craig Hill (2018), retrieved from Digitalisation in humanitarian assistance: Towards a stronger response, retrieved from: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/articles/digitalisation-humanitarian-assistance-towards-stronger-response.

- Denskus T. (2020), Racism in the aid industry and international development-a curated collection, retrieved from: https://aidnography.blogspot.com/2020/06/racism-aid-industry-development-curated-collection.html

- Digital Dignity in Practice: Existing Digital Dignity Standards, Pursuing Digital, retrieved from: https://www.wiltonpark.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Background-paper-Digital-Dignity-in-Practice-WP1698.pdf

- Donahoe E. – Just Security (2014), Human Rights in the Digital Age, retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/12/23/human-rights-digital-age#

- Drury F. (2017), Did Ed Sheeran commit ‘poverty tourism’ in charity film?, retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-42268637

- Fondation Suisse de Déminage (2016) Drones in humanitarian action: a guide to the use of airborne systems in humanitarian crises, retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Drones%20in%20Humanitarian%20Action.pdf

- Heeks, R. (2017), Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D)

- ICRC, Privacy International (2018), The humanitarian metadata problem: “Doing no harm” in the digital era, retrieved from: https://www.privacyinternational.org/report/2509/humanitarian-metadata-problem-doing-no-harm-digital-era.

- Journal of International Humanitarian Action (2020), retrieved from: https://jhumanitarianaction.springeropen.com/

- Kaspersen A., Lindsey-Curtet Charlotte (2016), The digital transformation of the humanitarian sector, retrieved from: https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2016/12/05/digital-transformation-humanitarian-sector/

- Lentfer (2017), Means, ends, and poverty porn, retrieved from: https://thousandcurrents.org/means-ends-and-poverty-porn/

- Lobb A., Mock N. (2007), Dialogue is destiny: managing the message in humanitarian action, retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18087912/

- Lunt A. (2017), Messaging apps: the way forward for humanitarian communication?, retrieved from: https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2017/07/25/messaging-apps-way-forward-humanitarian-communication/

- Meyer L. (2021), Creating Conditions for a Decolonised Digital Rights Field, retrieved from: https://digitalfreedomfund.org/creating-conditions-for-a-decolonised-digital-rights-field/

- Microsoft (2017) Microsoft policy papers: A Digital Geneva Convention to protect cyberspace. https://query.prod.cms.rt.microsoft.com/cms/api/am/binary/RW67QH

- Neuman, M. (2017), Dying for humanitarian ideas: Using images and statistics to manufacture humanitarian martyrdom, retrieved from: https://www.msf-crash.org/en/publications/humanitarian-actors-and-practices/dying-humanitarian-ideas-using-images-and-statistics

- Orgad S., Vella C. (2012) “Who Cares? Challenges and Opportunities in Communicating Distant Suffering: A View from the Development and Humanitarian Sector, retrieved from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/44577/1/Who%20cares%20(published).pdf

- Roby C. (2017), Opportunities and risks for messaging apps in the development sector, retrieved from: https://www.devex.com/news/opportunities-and-risks-for-messaging-apps-in-the-development-sector-89596

- UKEssays (2020), Media Effectiveness of Humanitarian Responses to Crises, retrieved from: https://www.ukessays.com/essays/media/media-effectiveness-of-humanitarian-responses-to-crises.php

- Wara Lotta (2020), The Synergy of Digital communication in Humanitarian intervention, retrieved from: https://wpmu.mah.se/nmict201group2/2020/03/30/digital-communication-humanitarian-emergency-fundraising-campaigns-awareness-raisingresponse/