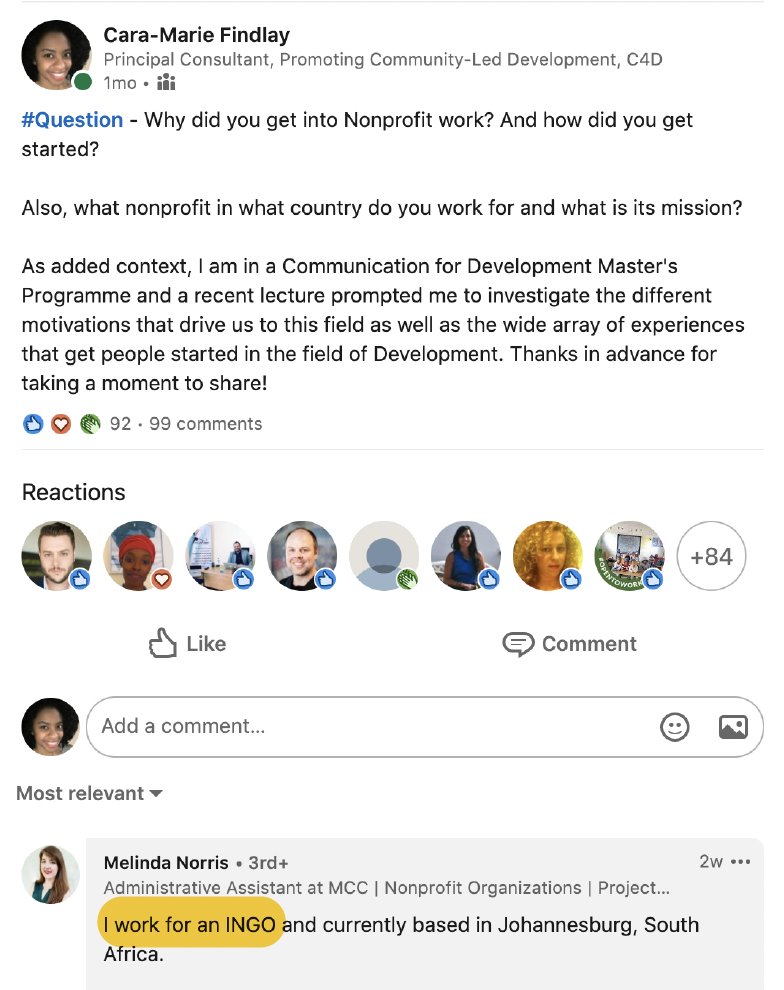

By Cara-Marie Findlay

Humanitarianism can be described as a “response to distant suffering, whether this distance is actually geographical or geopolitical (historically derived inequalities characterized by an economic disparity) that includes an explicit or implicit claim for the moral and political basis of its engagement” (Richey, p. 627). As practitioners engaged in reflexive work, we should conduct regular self-assessments to gage our own current response to suffering. After all, one risk we run, in being immersed in development work, is that of desentisation, or a diminished emotional response to a stimulus (e.g. distant suffering) after repeated exposure to it. We should also question what informs this emotional response.

Humanitarianism [and consequently Development] is still often explored in a North-South perspective (Richey, p. 628). As a practitioner who originates from the Global South, I became interested in learning more about the initial emotional responses (or motivations) that led my colleagues around the world to enter this particular line of work, and their relation to decolonising Development. One reason for this interest is because I have come to recognise the barriers that often exist for, and exclude, my fellow practitioners in, or from, the Global South.

My Background – What Informs My Emotional Response

I was born in Kingston, Jamaica. The majority of my extended family on my father’s side still reside in the country. As a first generation immigrant child in a U.S. public school system, I quickly learned to think of my native country as “Third World.” However, never in all of my schooling was I introduced to the concept of Development. I knew many programmes had been undertaken in Jamaica to improve the state of the country, and yet not much had changed for many of my family members back home, and in some instances, things became worse. I knew many people saw my home country as a place to be enjoyed for it’s all-inclusive holidays, or else to be pitied and helped through missions trips and donations. This created a tension within myself because of the general sense of pride I, and many of my people, feel. Yet, it wasn’t until I began working as an independent consultant with non-profits that I became introduced to the world of Development and NGOs and began to understand the systems in place affecting targeted peoples. I created a consulting company to help ensure that more underrepresented and impacted peoples would be able to participate in the Development dialogue and process taking place at all levels—local, regional, national, and international.

Figure 1 – Diagram – How structural racism shows up in the [Development] sector

Lack of awareness of the sector, and implicit bias in recruiting for the sector, are but two of the many barriers that prevent people in, and from, the Global South from participating in the field of Development.

I wondered how my own path to the Development sector differed or aligned with the individual journeys of my colleagues, and so I posed a similar question in different practitioner groups:

Why did you get into the field of Development? And How did you get started?

The Responses

The responses varied across the board, though there were a few common threads. For example, the role of family. Several commenters from both the Global North and Global South shared the role their families played on their path to Development and Social Change work:

- “I inherited it in my DNA. My dad was…a real trail blazer and part of the Chicano movement…” – Emily Escalante

- “I have several other family members that were in the Peace Corps…I was fascinated by their stories…” – Lea Dooley

- “My interest started with USAID’s pamphlets – 1975 – on fertilizer, that my grandpa…red and collected” – Adèle Raheliminhajandralambo

- “…my parents both had careers in the field with various NGOs….it was a field I’d been exposed to my whole life.” –

A few commenters assumed to be from the Global North mentioned the role trips to other countries played in their motivations:

- “…a college trip to Honduras” – Matthew Johnson

- “…a missionary trip to Nicaragua…” – Amanda Shelnutt

For many of the commenters from (or assumed to be from) the Global South, seeing a need that was not being effectively addressed, or their own experience with the challenges that come from growing up in a more vulnerable region informed their decisions to get involved:

- “…I founded Afrikala Arts with the need to support people going through mental health related challenges [in Kenya].” – Marlene Kinyua

- “I grew up in Kodaikanal…South India….I grew up without electricity. Now, I am working for a Non Profit whose mission is to end power poverty.” – Paul R.

- “I founded a nonprofit because of the need I saw at that time.” – Dr. Adefunke Adescope

- “I’m Native Hawaiian…I didn’t have a lot of role models that looked like me…Ho’omau Foundation. Our purpose is to support the success and development of Pacific Islanders.” – JoNelle Sood

- “I began non-profit org…to stop the genocide of the Rohjngya [by the Myanmar military].” – Seema Ahmad

- “I am the founder and chairman of the afflicted children’s development organization. Children living on the street….I was a victim.” – Santigie Kargbo

- “…to assist victims of the most neglected war in Southern Cameroons…” – Esther Bakume

A handful of responders assumed to be from the Global North based on their photos and/or current geographic location shared a more generic response: “I wanted to make a difference.”

Several respondents said they got their start in the field through volunteering. Though significantly more people from the Global North said that was the case, while only one response from the Global South cited volunteerism.

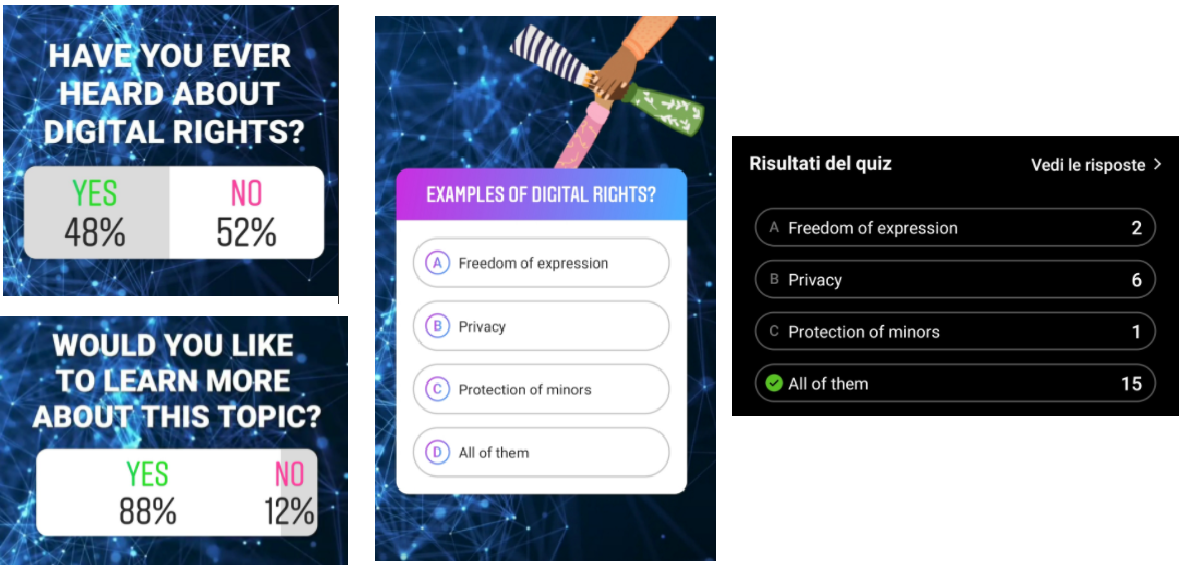

Methodology

The brief analysis in this post is based on comment discussions in answer to a question I posted in several LinkedIn and Facebook groups on September 16, 2021. While this is a prime example of the way new media, like social media platforms, can facilitate important discussions around Development, there are also some obvious limitations to this type of approach. To include: selection/sampling bias – the groups I posted in differed wildly from a Black Women in Development Facebook Group, to a Work with USAID LinkedIn Group, to a general international Non-profit Network LinkedIn Group. Thus, this is by no means a comprehensive representation of practitioners in the International Development sector. Additionally, we must assume response bias is also present. Practitioners in the Global South may not be aware of these particular social media communities and/or may not have access to an affordable or stable internet connection that allows them to regularly check in and participate in these group forums. Furthermore, the question was posed in English which may have prevented natives of other languages from participating. It’s also interesting to note, that the post that received the most traffic in the form of comments (Nonprofit Network – International) was also boosted by one of the group’s administrators.

I did disclose in each group where I posted that I was a student in the Communication for Development Master’s Programme. Although, at the time I asked the question, I did not know that I would be analysing and sharing some of the responses on this blog.

Conclusion

Every practitioner’s journey is unique. Our emotional response to suffering is informed by our backgrounds. To be an effective and ethical practitioner we must engage in reflexive practice and question our motivations, processes and procedures.

In May 2021, Peace Direct published a report, entitled Time to Decolonise Aid. The report includes the diagram above (Figure 1) as well as discussed structural and procedural barriers in the current aid, development, and humanitarian system.

If we are to truly decolonise aid, development and humanitarian work, then we must be able to identify and address our own emotional response (including biases) and what informs it (is it Eurocentrism? Black liberation? Something else?) as well as work to eliminate the barriers that prevent others who bring difference, especially those in, and from, the Global South, from engaging in Development as not only practitioners but also as experts. As one respondent from the Global North said in answer to my question, “it takes serious connections to get into this line of work!” Connections that often time people in, or from, the Global South do not have. This makes it even harder for people from the Global South to engage as practitioners and for them to be valued for their expertise. As the Time to Decolonise Aid report states, “The devaluing of practitioners from non-Western contexts is due in part to their being viewed as would-be ‘beneficiaries’ of any programme that might be implemented – they are assumed to require saving, thus making it incongruous that they may be qualified, have certain skills and be able to provide aid themselves” (Page 25). Yet the truth of the matter can be summed up in this quote from one of the report’s informants:

“National staff and Global South staff bring particular skills, competencies and experience to the sector. Often, we can offer special insight into the dynamics of a conflict, born of our lived experience. In some cases, we speak local languages. Our backgrounds can mean we’re adaptable in maddening conditions. Clearly black aid workers have a lot to offer the humanitarian sector when given the chance. Still, we’re not valued by the powerful agencies and their Western staff who run the sector. We had no idea that the colour of our skin would define our work so deeply to the extent of questioning our ability, enthusiasm and purpose in life.” – Tindyebwa Agaba (Page 25)

References

Peace Direct (2021): Time to Decolonize Aid-Insights and Lessons from a global consultation. London: Peace Direct.

Richey, L.-A. 2018: Conceptualizing “Everyday Humanitarianism”: Ethics, Affects, and Practices of Contemporary Global Helping, New Political Science, 40:4, 625-639.