“Any journalist going to cover a protest gets a gas mask, gear and training. That should apply online too,” said Julie Posetti. “News organisations must respond, but they can’t fix the problem… which is technological and political.”

Julie, who is Global Director of Research at the International Center for Journalists (ICfJ), was speaking in April this year at the launch event of a UNESCO report exploring global trends in online violence against women journalists.

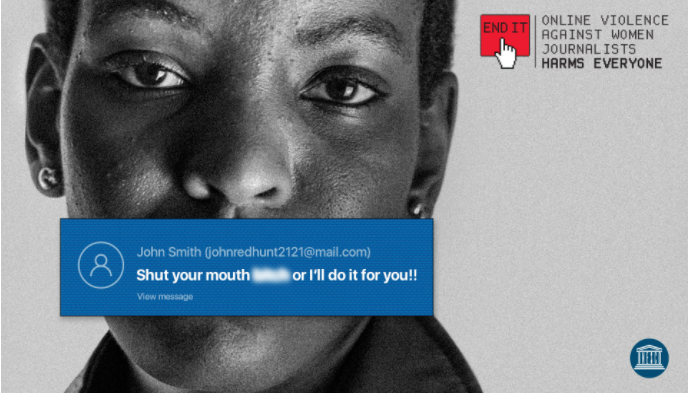

One month earlier, UNESCO had unveiled a social media campaign using the hashtag #JournalistsToo, to raise awareness of the prevalence and impact of online violence against women journalists.

“The Chilling” report launched at that event documents how online attacks against women journalists are becoming more prevalent and organised. It also details how social media is increasingly being weaponised by politicians, biased media outlets and purveyors of disinformation, who operationalise gendered online abuse to “chill” critical reporting (UNESCO 2021).

The paper is based on a range of research including:

- A global survey of 901 journalists from 125 countries conducted in five languages;

- Long-form interviews with 173 international journalists, editors, and human rights and digital safety experts; and

- Two big data case studies assessing more than 2.5 million Facebook and Twitter posts directed at two prominent women journalists (Maria Ressa in the Philippines and Carole Cadwalladr in the UK).

While the Chilling report recognises that online violence against women journalists is a worldwide problem, it is some of the first research on the topic to really emphasise how the issue comes with disproportionate offline impacts and complex intersectional challenges in the Global South.

It shows how intersecting spectrums of exclusion – including gender, ethnicity, social class and geography – make women journalists more vulnerable to attack in the online world, and it suggests ways in which governments and big tech companies can work to counter this.

Before we dive deeper into the findings of the paper, it’s important to understand what we mean when we talk about gendered online violence. According to UNESCO, this type of violence can be understood as a combination of:

- Misogynistic harassment, abuse and threats online.

- Digital privacy and security breaches that increase physical risks associated with online violence.

- Coordinated online disinformation campaigns leveraging misogyny and other forms of hate speech.

With that definition in mind, let’s get into the details, and later, some possible solutions.

New forms of gender-based violence

From a high-level perspective, we know that information and communication technologies (ICTs) mirror society and can only ever be an enabler for human activities. So just as women suffer gender-based violence in the offline world, we see online spaces playing host to new forms of violence, curbing women’s freedom of expression in a gendered way (O’Donnell & Sweetman 2018).

This is borne out by research showing that women and minorities face a disproportionate amount of organised harassment from mobs of pseudonymous accounts on platforms such as Twitter (Tufekci, 2017, p172).

The academic Jin Lee (2021) cites Banet-Weiser (2018, p156) to explain how misogyny breaks out online as a form of popular culture, or “popular misogyny”, where women seem to win visibility thanks to the popularisation of (post)feminism. She posits that men feel as though they are “losing in the economy of visibility”. Thus, in a bid to “reset the gender balance back to its ‘natural’ patriarchal relation,” popular misogyny attacks visible women through the media. There are few more “visible” women online than women journalists, so it follows that they would be likely targets for such attacks.

To many of you reading, it will come as no surprise that this kind of online violence against women journalists appears to be increasing, particularly in the context of what UN Women calls the “shadow pandemic” of violence that women experienced during COVID-19. This is compounded by the fact the pandemic has changed journalists’ working conditions, making them even more dependent on digital communications services and social media channels, therefore exposing them to increased online harassment (ICFG 2020).

The statistics collected by UNESCO corroborate this and paint a troubling picture, with nearly three quarters (73%) of survey respondents saying they experienced online violence. Of these, 25% suffered threats of physical violence and 18% were subjected to threats of sexual violence.

Not only did respondents suffer misogyny and sexism, but this intersected with racism, religious bigotry, sectarianism, ableism, homophobia and transphobia, producing heightened exposure for women experiencing multiple forms of discrimination concurrently, often in the Global South, as detailed in the report’s case study on Maria Ressa.

The case of Maria Ressa

Maria Ressa is a Filipino-American journalist who founded the Manila-based news site Rappler. She’s also a former CNN war correspondent, laureate of the 2021 UNESCO World Press Freedom Prize and Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

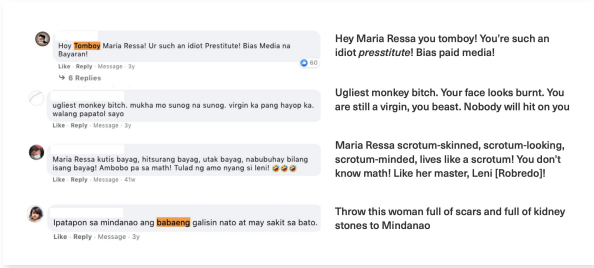

Since the Philippines’ 2016 election, Ressa has faced a barrage of online abuse on a daily basis including death threats, rape threats, doxing, racism, sexism and misogyny – delivered in mediums ranging from text and images to memes.

In addition, Ressa has been the subject of hashtag campaigns such as #ArrestMariaRessa and #BringHerToTheSenate, designed to encourage online attack mobs and discredit both her reporting and the media outlet she founded.

At one point, in response to her investigations into government-linked disinformation, she recorded receiving more than 90 hate messages an hour on Facebook (Ressa 2016).

UNESCO’s analysis found that while a coordinated and vitriolic mob of digital aggressors instigate and fuel the attacks on Ressa, Facebook (which acts as the de facto internet in the Philippines) is the major vector for the disinformation-laced online violence she experiences.

This chimes with internal Facebook documents recently made public by whistleblower and former Facebook employee Frances Haugen (Chappel 2021). Although it should be said that an official statement from the company insists hate speech on the platform is falling: apparently by almost 50% in the last three quarters of this year.

For Ressa, her online abuse has been more harrowing than her experience working as a war correspondent. She is therefore firm in her belief that social media platforms need to undergo radical renovation – of both their business models and design – to stop the toxicity that she says overruns them.

“I don’t think anything is possible until we clean up the information ecosystem, until you stop the virus of lies,” she told UNESCO. “It’s a perfect comparison to the COVID-19 virus because it is very contagious. And once you’re infected, you become impervious to facts” (UNESCO 2021, p68).

It is pertinent to note that the information ecosystem to which Ressa refers is largely designed and overseen by men. Careers in tech design and development are dominated by men in the Global North, therefore digital applications are more likely to be tailored to their interests and needs (O’Donnell & Sweetman 2018). It could be that meaningful change must actually begin with tackling this discrepancy and dismantling the power imbalances that exclude women from shaping the digital world around them.

Holding the platforms accountable

Ressa is pessimistic about the prospect of the platforms responding quickly and effectively enough without changes to accountability and liability. “The only way it will stop is when the platforms are held to account…because they allow it,” she said. “It’s kind of like if you slip on the icy sidewalk of a house in the US, you can sue the owner of the house. Well, this is the same thing. They have enabled these attacks” (UNESCO 2021, p69).

In the Philippines, Ressa is meanwhile appealing criminal charges for “cyber libel” as she continues to endure daily attacks from a pro-government army of trolls. On the one hand, Ressa may be subject to a higher volume of attacks than other women journalists, due to the highly “visible” nature of her work. However, the flip side is that she has a bigger platform on which to fight back, with frequent appearances in English-language media. This arguably offers her a layer of protection that less prominent journalists in the Global South do not have access to.

In a demonstration of her influence, Ressa’s calls for regulation are beginning to garner wider attention. Earlier this week, she featured in a Bloomberg article in which she argued that technology companies must face greater regulation globally to curb disinformation on social media. In the same article, she criticised Facebook for being “biased against facts” (Calonzo & Lim 2021).

While it might not help Ressa’s case directly, there are glimmers of hope in Europe for the kind of laws that she and UNESCO would like to see enacted around the world.

Last month, 26 rights groups including Amnesty International and AlgorithmWatch urged European lawmakers to use the proposed EU Digital Services Act to punish platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter if they fail to crack down on abuse targeting women (Goujard 2021). Representatives in the EU Parliament have already introduced amendments to the legislation that would make platforms responsible for removing illegal content that targets women, while the United Kingdom is also working on its own draft Online Safety Bill.

Beyond the headlines

Online violence against women continues to make headlines, but what is needed are concrete solutions beyond words of support and measures to “empower users”. When social media platforms fail to take decisive action to stop online violence, it has real impact – not only on the lives of victims, but also on democracy, press freedom, and gender equality.

For me, this issue is close to home. I worked as a journalist for 12 years before trading the newsroom for a career in communications. In my early days as a print reporter – when my byline would be published on everything I wrote – I was somewhat insulated against attacks by the medium itself, since print offers fewer opportunities for audience engagement (although I did receive the odd angry letter from a disgruntled reader). Then when much of our work moved online, I was employed as an editor behind the scenes, protected by the kind of anonymity that simultaneously emboldens many who perpetrate digital violence. It is clear that anonymity can be a tool for good or ill, and in my case, the protection it offers is the primary reason I decided to write this blog using a pseudonym. Most working journalists do not have that luxury (nor should they if we want an open and transparent press).

Writing on the New Media, New World blog – both in this post and my two earlier contributions (which you can see here and here) – really brought home to me the problems outlined in the Chilling report. The ability for journalists and readers to interact online offers benefits for both – democratising access to information, providing increased opportunities to hold powerful parties to account and giving people platforms for “talking back”. However, checks and balances are required to ensure women in the media are able to continue delivering this vital public service.

Changes to legislation are no doubt welcome, but as Ressa and the UNESCO report recommend, social media companies must go further and tackle their algorithms, which too often amplify online violence against women.

As much as the online world offers potential for angry and alienated users to attack women, it also provides channels to fight such violence. While we wait for governments and big tech to get their acts together, I for one will be using the hashtag #JournalistsToo and doing my best to claim the digital spaces at our disposal.

What do you think should be done to protect women journalists against online attacks? Do governments need to take action? Or is it up to the platforms to lead the way? I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts as always, dear reader.

And in case you’re interested. Who am I?

- A journalist-turned comms professional

- A student on Malmö University’s Communication for Development MA

- One member of the four-strong team of women behind New Media, New World.

Thank you for being here : )

References

Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism and popular misogyny. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Calonzo, A. & Lim, M. (2021). Nobel Winner Maria Ressa Demands Laws to Fix Facebook’s ‘Bias Against Facts’. Bloomberg, October 26, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-26/nobel-winner-demands-laws-to-fix-facebook-s-bias-against-facts

Chappell, B. (2021). The Facebook Papers: What you need to know about the trove of insider documents. NPR, October 25, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/25/1049015366/the-facebook-papers-what-you-need-to-know?t=1635613442635

Goujard, C. (2021). Advocates have a message for social media platforms: Protect women. Politico, September 30, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/advocates-have-a-message-for-social-media-platforms-protect-women/

ICFG. (2020). New Global Survey Raises Red Flags for Journalism in the COVID-19 Era. ICFG, October 2020 https://www.icfj.org/news/new-global-survey-raises-red-flags-journalism-covid-19-era

O’Donnell, A. & Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development. Volume 26, Issue 2, pp217-229.

Lee, J. (2021). Mediated Superficiality and Misogyny Through Cool on Tinder. In Pooley, J. (2021). Social Media & the self – An open reader. mediastudies.press.

Ressa, M. (2016). Propaganda war: Weaponizing the internet. Rappler. October 3, 2016. https://www.rappler.com/nation/propaganda-war-weaponizing-internet

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas – The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

UNESCO (2021). The Chilling: Global trends in online violence against women journalists. UNESCO, April 2021. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/the-chilling.pdf

UN Women (2020). The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against women during COVID-19. UN Women, May 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19