Hello reader. Hello ComDev community.

What comes to your mind and how do you feel when you see #BlackWoman, #SayHerName, #NotAnotherAuthor, #BBCBias and #NotGoodEnough? Such emotionally charged hashtags used in social media activism tend to immediately catch our attention, and we want to understand, to join in and to achieve or restore social justice.

This blog post is written primarily for the Malmö University’s ComDev Master programme community as a follow up to my essay assignment submitted last semester (Spring 2021) for the course “Communication, Culture and Media Analysis”, Theme 4 – Difference and Power: Representations of Gender, Race and Class. My topic was ‘“Another author”, Twitter and novels for social change’ and the reason to come back to it in this blog post is the excellent opportunity to respond to peer review that suggested to clarify my motivation behind choosing the text for analysis. As my essay’s subject is closely linked to New Media, New World’s core theme (new media, activism and development), I happily take this chance to say more.

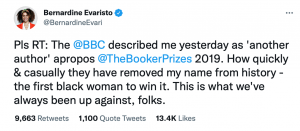

My essay was based on a tweet by the contemporary British novelist Bernardine Evaristo, that she wrote as a response to the 2019 Booker Prize winner announcement by a BBC news presenter on a television program, where he excluded her name in saying that that year the award was shared between the renowned writer Margaret Atwood (for “The Testaments”) and “another author”.

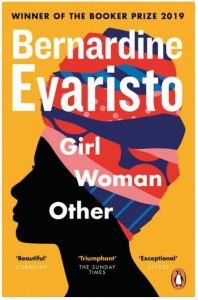

Briefly, the Booker Prize is a high-profile literary award in the British culture and grants significant international publicity. Bernardine Evaristo is the first black woman and the first black British person to win this prestigious award for her eight domestic fiction novel “Girl, Woman, Other”. It depicts experiences of black British women and their struggles with various forms of oppression and portrays their agency in addressing racism, inequality and stereotypes.

The tweet was followed by a wave of support (9,800 retweets using hashtags like #BlackWoman, #SayHerName, #NotAnotherAuthor, #BBCBias, 1,100 quote tweets and 13.6k likes, including a retweet by Margaret Atwood;). BBC apologized by saying that the presenter was speaking live without a script.

My academic essay looked at structural erasure in representations of black women in modern British society and analyzed the tweet within a theoretical context of “otherness” and black feminism, as well as explored the potential of Twitter’s connective action to foster social change. Analysis of intersectional gender and race representation in traditional (BBC) versus social media platforms demonstrated that new communication forms can help the silenced voices of excluded groups of “others” be heard.

How did I come across this topic? Back in January 2021, we read “Girl, Woman, Other” in a local book club together with a group of expat friends in my host country Germany. At that time, this book had become very popular and was trending in various book clubs internationally. The great interest was probably sparkled by addressing issues of immigrant communities, race, gender and identity (Bernardine Evaristo herself has a mixed cultural background: she was born in London to a white English mother and a Nigerian immigrant father). Just read this excerpt to get a sense – one of the characters was trying to discover her lost heritage (pp.446-448, note that the text omits conventional punctuation):

“Great news! Your Ancestry DNA results are in. The moment you’ve been waiting for is here . . .

in her case – all her life

Penelope clicked on the hyperlink without delay <…>

Penelope went straight to the drinks cabinet; a few hours later she made it to her bedroom to lie down

being Jewish is one thing but never in a million years did she expect to see Africa in her DNA, that was the biggest shock of all, the test didn’t provide answers, it confronted her with questions

as she lay there, she imagined her ancestors attired in loincloths running around the African savannah spearing lions, at the same time wearing yarmulkes, eating open-topped rye sandwiches and paella, and refusing to hunt on the Sabbath

perhaps she should get a dreadlock wig in keeping with her new identity, become one of those Rastafarians and sell drugs

at least it explained one thing to her, why she tanned as soon as the sun hit her skin

<…>

her African ancestors were probably nomads roaming over the continent killing each other before the British demarcated regions into proper countries and thereby imposed discipline and control

if she was 13% African did it mean one of her parents was 26% African? or was it divided between both of them?

as she didn’t know who her birth parents were, she couldn’t even begin to work out which strand belonged to which one”

So this blog post is also a recommendation to add “Girl, Woman, Other” (or any other book from the “Black Britain: Writing Back” project, curated by Bernardine Evaristo) to your personal non-academic reading list or to pick it as the next read for your upcoming book club gathering.

“Girl, Woman, Other” and the controversies around it are an excellent example of how new media can help transform structurally embedded inequalities. My essay examined an online cultural protest, but many of the above-mentioned hashtags are used in global political movements such as #BlackLivesMatter. My next blog post will further address social media’s engagement in advocacy for the “social out-groups”, stay tuned.

Bernardine Evaristo, Girl, Woman, Other (2019). Penguin Books UK