In the first part of this post, I discussed how Martin Luther took advantage of the communication technology of his time, the printing press, to advance his cause in the Reformation era. This was during a time when early critics within the church did not see any benefit in using printed tracts to court the public. (Pettegree and Hall, Reformation and the Book: A Reconsideration, 2004 p.785). I also talked about how improvements in the personal computer in the 1980s made it the perfect tool for Tim Jenkin to use to enhance secret network communications in the ANC’s Operation Vula project.

For Luther, the Gutenberg’s printing press and the printing industry had been around since the 1400s, so by 1517, he was well aware of its use and benefits. However, he was not a printer or publisher, he depended on the printing industry and its already existing networks to spread his ideas.

What worked for him was that his… arguments quickly touched a nerve with a broad German public; and…printers in a large number of German cities easily seized on the opportunities presented by the resulting controversies to enter the market for vernacular Flugschriften [pamphlets].(Pettegree & Hall, Reformation and the Book: A Reconsideration, 2004 p.786). Luther used this situation to his advantage by prolifically speaking and publishing his writings and this contributed to the spread of reformist ideas in Europe.

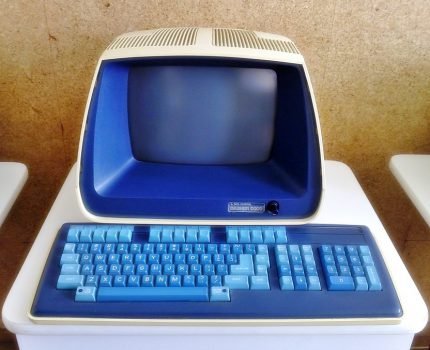

In Jenkin’s case, personal computers had been around since the 1970s. By the 1980s, they had become affordable for him to research their capabilities, purchase them, and experiment different communication approaches.

To establish a secret computerised communication link in South Africa, Lusaka, and London, Jenkin and his colleague Ronnie Press (both working as activists providing technical assistance to the ANC) experimented with a creative mix of devices to address errors in transmission including, electronic mail service, paging devices, walkie-talkies, radios, telephone lines, different types of modems, tape recorders etc. This led to Jenkins improving his skills in computer programming. Technological advancements in communication within South Africa such as the introduction of radio telephones, and phone cards for public phones greatly aided the technical team’s progress.

During the development phase of Operation Vula’s communication network, Jenkin and Press, working from London, collaborated with a number of personalities including, Conny Braam, the head of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement who then recruited “a suitable playboy type” to test devices in South Africa, and “a sympathetic KLM air hostess” to shop for a radio telephone in South Africa. However, they faced the challenge of convincing ANC leaders about the importance of establishing a secret communication system in their underground operations in South Africa that would enable dialogue between ANC operatives and exiled leaders.

The development phase of Operation Vula began in 1984 but it was only in 1987 that Jenkin met one ANC leader, Mac Maharaj, of whom he states…Mac was the first ANC leader I had come across who had the foresight to realise that nothing serious could happen in the underground until people could communicate properly. Mac’s interest, support, and active participation in testing and using the computerised communication system contributed to the establishment of the networked communication link in Operation Vula.

By August 1988, Operation Vula had secret communication lines between London, Lusaka, and South Africa; and messages between ANC operatives and exiled leaders could be sent and received on the same day. According to Jenkin, The link not only served as a channel for dialogue and information transfer but also for a number of other purposes such as making requests, issuing criticism and arranging meetings. This transformed the nature of Operation Vula in terms of the speed of communication exchanges and the disappearance of inertia. According to Garrett & Edwards (2007), existing discussions of Operation Vula led them to conclude that the project’s encrypted communication system played a pivotal role, fundamental to the movement’s success.

Luther and Jenkin may be of different eras, however, their stories show ways they used the communication technology available to them to advance their cause. In reviewing their stories, one thing becomes increasing clear to me: Technical capabilities and limits shape, but do not determine, how a technology is used (Garrett & Edwards, 2007). What are your thoughts?