The infiltration of the digital in all areas of life has brought an added dimension of observation for development studies and practice. Quick advancements in information communication technology (ICT) raise many new questions on both the possibilities and the risks digitalisation brings to the implementation of development policies and projects. In this module we have examined three themes: (1) how ICT influences the thinking and the doing of development; (2) how new media and activism play a role in shaping core concepts of development and (3) the impacts of big data on the agenda setting of international development.

My first blog Representation in Development: the power of crowdsourcing stock images critiques search engines and image databases as they operate from the baseline of whiteness – where representation of people of color is limited and stereotyped. Crowdsourcing has offered a solution to this, placing representation in the hands of photographers and illustrators from the global south. Blog 2, Digital Archiving: Instagram as a tool for decolonization, speaks to the particular relationship the postcolony has to knowledge formation – emphasising the importance of decolonizing knowledge systems by rebuilding the histories of the postcolony. The blog entry also puts forward the connection between our understanding of the past and our visualisations of the future, and that curation, archiving and presentation of knowledge is political. Blog #3, Resisting Development- activism through Facebook, examines how digitalisation is affecting development work (Tony Roberts ICT4D) – specifically how the use of social media in activist movements is breaking down the binary spatial imaginary of the developed and developing world, typical to development, instead presuming chaotic pluralism.

All three blogs pay special attention to how new media (Facebook, crowdsourcing, online image databases, Instagram) facilitates the re-conceptualisation of development. This final blog will continue to examine this common thread expounding further on how the pluralistic nature of social media is enabling new voices to the forefront forcing us to reconsider what we mean by development.

Transforming knowledge building, action and outcome through new media

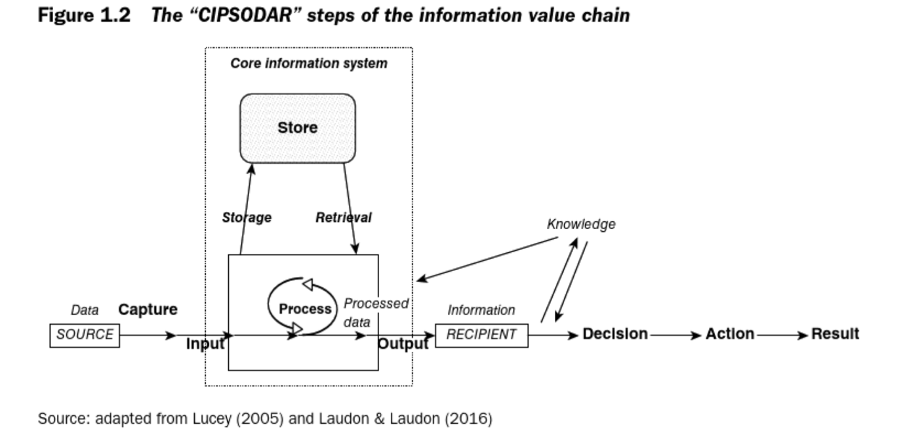

In the 21st century communication technology has advanced in such a way that allows engagement and mutual exchange of information. As opposed to print, radio and television that are one-way flows of communication new media has provided a platform for conversations to unfold in a global, highly responsive and public arena. New media has the distinct characteristic of being collaborative – where unsuspecting posts become viral, hashtags spur global social movements and images transformed into memes are used to critique society or to entertain. The pervasiveness of communication becomes starkly clear in the dynamics of social media, where feedback systems and the reshaping of messages take place several times along the communication value chain. Applying Heeks CIPSODAR model, where he maps out the steps of how data becomes information and then knowledge (Heeks, 2017:7,8), one can see how social media amplifies the rate and volume of information. The feedback system of social media is so vast and quick that netizens continuously repackage information on the internet in relation to the subculture, online communities and trends that they are active within.

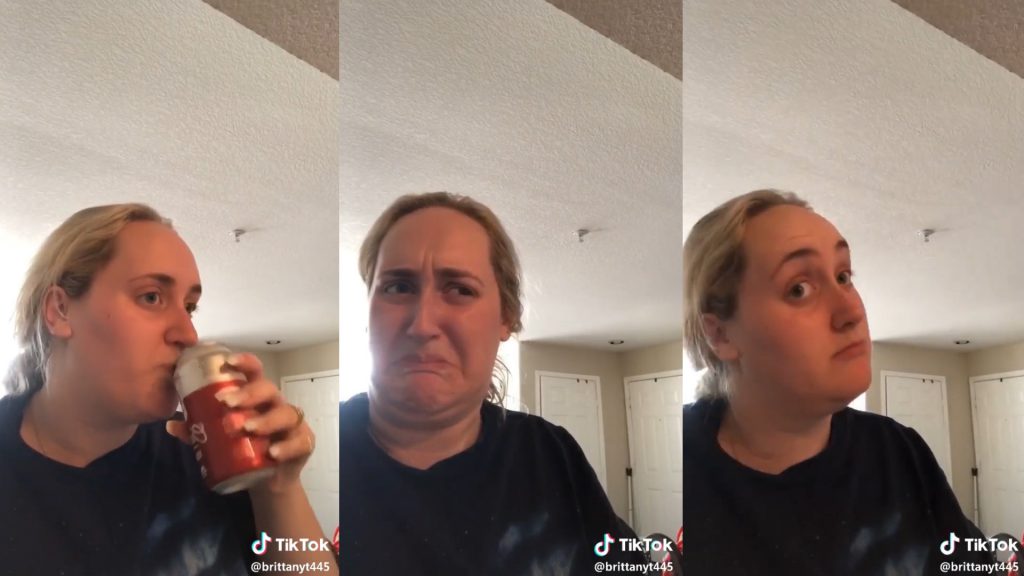

Take for example the kombucha girl, which originally was a video of a girl reacting to tasting the fermented drink kombucha for the first time. The progression of her facial expressions as she first dislikes and then reconsiders the drink were so relatable that screengrabs of the video were taken and made into a meme. The meme has been remade hundreds of times to convey various messages, from political expressions to workplace jokes and existential reflections on humanity. This constant and quick repackaging of information reflects the hundreds if not thousands of ways that information is processed into knowledge depending on context of the user on the other end – effectively allowing a vast number of interpretations of information to manifest, and consequently just as many actions and outcomes. Kombucha girl is just one out of the dozen viral memes to circulate the internet per year.

It may seem like a stretch to consider kombucha girl memes as knowledge, and it might seem especially irrelevant to development practitioners, but what is valuable is to take note of how information is picked up, who transforms it and how it is quickly dispersed. The virality of memes point to a common feeling or understanding that an internet community shares. It connects individuals across space and culture simply by sharing sentiments online. What does this mean for development? For one, it displaces power dynamics outside of the particular institution doing the messaging, instead leaving the virality of a message to be determined by the ordinary citizens of the internet. With exemptions that will be mentioned later, the digitalization of communication has also made it harder to control or censor comments posted or shared via social media platforms. This forces powerful individuals and corporations to be held accountable for the mistakes they make. One example is this video clip of a Boewulf executive who boldly mentions that Jokkmokk has no local population when confronted with questions on the impact of mining in the area. The clip went viral in resistance groups on Facebook and lead to the the establishment of the webpage www.whatlocalpeople.se and a media mention. Lastly, examining communication in the context of development in a digital world (Roberts 2019) the rippling impacts of communication through new media point to the need to re-design how we plan, execute and evaluate development projects.

Dorothea Kleine illustrates in her case study of telecenters in Chile (Klein 2010) that the impacts of ICT in development projects are widespread and difficult to quantify. Instead of assessing the success of the project through one outcome the results of the project are manifested in the many ways the existence of ICT in the village affected an individual’s resources. Klein mentions 9 types of resources: the material, financial, natural, geographic, human, psychological, information, cultural and social (Klein 2010;8). While the outcome of the telecenter project did not lead to a classic development outcome for the individual woman in the case study, the availability of a computer added freedoms to her information, psychological and material resources.

Decolonizing development

It has taken “development” scholars and practitioners about 80 years to agree that unending economic growth will lead to the destruction of our planet. And yet, almost 40 years after Amartaya Sen’s capability approach, and despite the newly established SDG framework, the sector as a whole still operates on theories of modernisation focused on correcting the global south.

If we take a step back and examine how the capabilities, or freedoms, of the “developed” global north have come to be it is apparent that modernisation theory will never make these freedoms universal. The rapid economic growth that enabled institutional, social, and cultural strengthening, propelling western populations into “modernity”, were contingent on the enslavement, exploitation and disenfranchisement of the global south (McEwan 2018; 99-148). The south has been central to the development of the north, not only in material resources but in man-power, skilled workers and knowledge (McEwan 2018: 271). The binary divide that modernisation assumes- of the developed and the under-developed – which also presupposes the spatial imaginary of the developed and developing world, not only disregards the vital role that the global south has had in expanding the freedoms of the north but also ignores the reality that the Other is living, acting and contributing in the north (Hooks 1992; Said 1978).

It must be clarified, that this blog does not argue that new media is the magic solution to inequitable development. Instead it argues that the reasons for continued unequal development lie not in the challenges and issues particular to the global south but in the values and systems instilled by the development sector. New media enables the voices of the distant Other, and at times the subaltern, to take space, to be amplified, to contest and to gain support. Whether it be through representation in stock image databases, through social media protest, or through open access archives, the anarchy of the world wide web provides opportunities for dissident voices of the development complex to be expressed and even, possibly, globally supported. Protest via social media, for example, has made it possible for a larger number of dispersed supporters to contribute to a movement through various political actions, like donating, advocacy, or physical support (Poell & Van Dijk, 2018;2). These degrees of involvement allow for individuals to support a cause to the extent of their ability or motivation. What forms the basis for solidarity with the movement need not be comprehensive or identical across supporters. Instead the expression of support of each individual and the affirmation this gives to the struggling community is what constitutes the action of protest. This pervasiveness of new media, its pluralism in messaging and its pluralism of support carries the possibility to change development discourse.

While new media opens up opportunities to those usually silenced to be heard, new media is not immune to structural biases. In Klein’s choice framework she rightly includes the influence of structures to agency (a.k.a. resources by Sen). Although agency may be increased through the introduction of ICT or through developments in new media these added resources will inevitably operate within pre-existing structures. Ruha Benjamin explains clearly how digitalisation is subject to racist structures and how “objective data” is filtered through subjective, historical understandings of reality.

… fast forward to the present, where people, companies, organizations, are employing all types of software systems to predict where crime will happen, in order to more empirically—we’re told—more neutrally, objectively, send police to go. These software systems rely on historic data about where crimes happened in the past, in order to train the algorithms where to send police in the future. And so if, historically, the neighborhoods that I grew up in were the target of ongoing over-policing surveillance, then that’s the data that’s used to train the algorithms to send police today, under the cover of a more objective decision-making process. And this is happening in almost every social arena. Policing is just one of the most egregious, but it’s happening in terms of education, which youth to label “high-risk,” for example; in hospitals, in terms of predicting health outcomes; in terms of which people to give home loans to or not, because of defaulting in the past. And so our history is literally being encoded into the present and future.

Ruha Benjamin interviewed on Fair.org

The complexities of development are apparent. However, instead of discounting these complexities and forcing development processes into linear cause-and-effect frameworks, development should make space for diverse approaches, including pluralistic and locally decided definitions of progress, freedoms, timelines and priorities. Diversifying approaches to development will necessitate confronting the colonial history of development and shifting our modes of design and measurement from quantitative to qualitative. Speculative designers Thirdspace eloquently phrase that the decolonisation of design resits the necessity to solve.

Why the resistance to solve? Well, because those who can afford to solve, do so. Yet sadly we find that they don’t solve, but rather shift the burden to those who don’t have the option to shift it any further. Because it is easier to patch and to fix the material world than it is to encounter ourselves and question our humanity. Who has reaped the fruits from the activities of the Anthropocene, yet, who will pay the price for it?

By way of introduction, thirdspace on Goethe.de

The Other is speaking; we are Here.

Personal reflections on blogging

The process of blogging has been unexpectedly challenging. Re-shaping the structure of my writing and the tone of voice from academic to journalistic has probably been my greatest struggle in this module. The pace of publishing is also very quick forcing me to quickly digest new material and to form an opinion that will be publicly shared. I must admit that while I find this kind of communication daunting, I do also believe that this kind of content creation is most suited to the communication landscape of today. Shaping ones writing in a way that is easily understood by the public, quickly written and widely dispersed is a necessary challenge for development communicators. Following my belief that development encompasses all actions, actors and sectors in society (rather than limited to specific development actors) communicating development challenges must be done in such a way that reaches the popular masses.

I found that I had no problem coming up with themes for my blog posts but I did find it challenging to situate my arguments and thoughts in a context that is interesting to the public but also coherent enough to be covered in a shorter format. Given that these posts are also situated in an academic course it was an added challenge to make adequate references to the course literature without boring the readers with academic obligations. I did hear feedback from some of my friends that my posts were abstract and hard to follow, speaking to the difficulty of tailoring content to the right audiences.

Sources

Heeks, R. 2017: Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D), Abingdon: Routledge.

Birhane, A. 2019: The Algorithmic Colonization of Africa, Real Life Mag, 9 July.

Sein, M.K., Thapa, D, Hatakka, M. & Sæbø, Ø. 2019: A holistic perspective on the theoretical foundations for ICT4D research, Information Technology for Development 25:1, 7-25.

Kleine, D. 2010: ICT4WHAT?—Using the choice framework to operationalise the capability approach to development, Journal of International Development 22:5, 674–692.

Poell, T. & van Dijck, J. 2018. Social Media and new protest movements, in: Burgess, J., Marwick, A. & Poell, T. (eds.): SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London: Sage.

McEwan, Cheryl. Postcolonialism, Decoloniality and Development, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

Jackson, J. 2019: Black Communities Are Already Living in a Tech Dystopia’, Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting, 15 August.

hooks, bell (1999), “Eating the Other”, in Feminist Approaches to Theory and Methodology. HesseBiber, Sharlene, Gilmartin, Christina & Lydenberg, Robin (eds). Oxford & New York: Oxford UP, 179-194.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.