Don’t we all prefer to have choices than to be thrust onto a certain path in life? The gratification one achieves from making that choice may not always be certain beforehand as is the case with most decisions we face, from the most existential of is there a God to which direction to go in town (Pascal, 1640).

In our current day and age one may assume that digital tools, with social media at the forefront, allow for an abundance of choices and granting empowering autonomy to users in making various decisions. It may lead to the point where at times an information overload due to increase access to information causes the phenomenon of overchoice, overwhelming a person with too many alternatives, as presented by late centrist futurist Toffler (1970).

In turn, an absence of choice may then also hinder progress, development, a way forward or sideways as it reduces one’s future to fewer alternatives. Hooks (1984) already points out the absence of choice for the oppressed, be it by social class, race or sex and gender. This lack of empowered choices in real and daily life, of where to go, work, study and more translates also to an absence of authentic representation and hence choice in the digital context as an extension of the traditional media landscape. While, as Hall (1984, p. 269) points out, there has been a large shift towards normalizing non-White (as well as non-male, non-upper class, non-heteronormative and more) popular representation, this representation still operates in systems of power so the representation also of choices that allow to move up within a given hierarchy is still much lower for marginalized members of society.

This can of course be extended across all genres of digital media, including digital games. The gaming industry in Europe is on a journey to become more diverse, however recent surveys highlight that there are still many steps needed as, again, diverse representation of society is much higher in lower positions than in those holding decision-making power. As this BBC article shows, many underrepresented talents in the industry move to setting up their own studios to work against this status quo of underrepresentation. With gaming being such “a reflective, empowering and emotional influence in the lives of players“ it is clear that the industry would do well in broadening its user and worker base along dimensions of race, class, gender, ability, age and more.

With digital storytelling being such a powerful tool to represent others and oneself there is value in looking at how marginalized people or communities have used those tools to further showcase heterogeneity when industry players still fail to do so? As Couldry (2008, p.17) points out that value may have such power in social and cultural transformations that it could affect democratic development at large.

Bridging the “digital divide” of who can access as well as shape digital industries is no longer a task that looks at a binary view of the global South versus the global North. It is much more a self-reflective approach needed to be undertaken by digitally savvy actors in any and all contexts. Benjamin (2019) pinpoints this demand for a reflexive approach on the current usage of digital technology as a potential reinforcement of existing inequities, when and if the processes of applying this technology is not done through a lens of empowerment, Critical Race Studies, inclusivity and more.

I want to take a look at two examples of how queer Black game designers in Europe have chosen the lens of empowerment to critically challenge the gaming industry and persisting hegemony of heteronormative Western societies. As Benjamin would potentially call their work, they are “countercodings that retool solidarity and rethink justice.” (Benjamin, 2019, p. 161).

The Wagadu Chronicles is a massively multiplayer online game (MMO) designed and developed by Twin Drums Studio in Berlin, Germany, and currently running a successful Kickstarter campaign.

This MMO concept focuses heavily on roleplaying, little on combat and strives to authentically portray various African cultures and landscapes. It also portrays proud elements of queerness and matriarchal societal structures in an anticolonial fashion as highlighted here by the Italian-Ghanaian founder Allan Cudicio. Its genre, Afrofantasy, brings African mythologies to the digital world stage. Cudicio combines the fantasy world with an extensive array of roleplaying opportunities that allow the players to not only experience various lineages, talents and skills, and character profiles but to switch between those, engage in deep dialogue and have agency in shaping the character and hence narrative development. Cudicio’s inspiration came from moments of despair when growing up, as he states in the article’s embedded interview:

“I think growing up, I just accepted that I was never going to be represented”

He turned to founding his own studio and utilising tools of the trade, digital storytelling, to apply his lens of empowerment to games development. Centring African characters with no possibility of choosing a white character is a strong stance against a normative player base and industry and a much needed step toward inclusive representation. It may empower players of African descent to go on a journey of recovery from the structural racism surrounding everyday life and reducing choices in real-life encounters.

As Cudicio explains in the game’s Kickstarter campaign video:

It’s not just about making the best game, but it is also about building a community. […] and building the first online Afrofantasy game, bringing underrepresented aesthetics and themes into the fantasy world.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/wagadu/the-wagadu-chronicles/description, Allan Cudicio

Twin Drums as a studio presents itself as “majority women, half black and a third queer“ in a clear message that identity markers, demands for accurate representation and a non-heteronormative lens are all relevant to their work and seek to in turn influence (challenge or empower) their user base.

The archivist, curator and game designer Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley takes a different approach to using digital game design, queerness and race as tools to dismantle white supremacy and its accompanying patriarchy in the global North.

The “admirable project of reclamation by which trans figures are rediscovered in the black queer archive and celebrated” (Green, 2016, p. 66) is no easy task and an unfinished journey considering how many Black trans narratives, successes and lives have been erased. Brathwaite-Shirley just recently stated how much more work lays ahead of her as well.

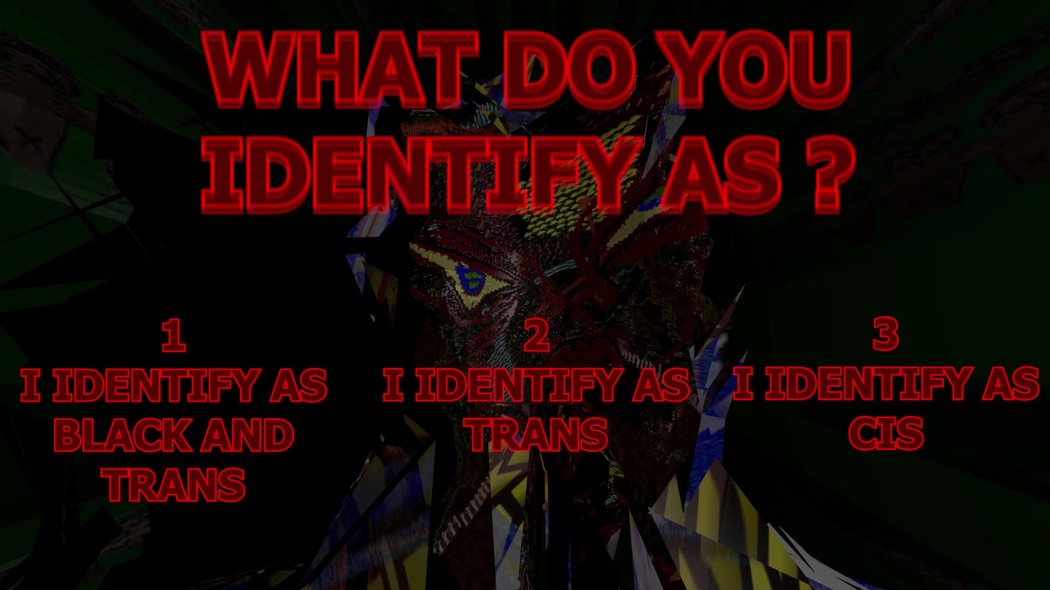

Entering the project www.blacktransarchive.com one is immediately made aware of the context of the game. It is a “pro Black, pro trans space” designed for Black trans people. As a white cis-woman I am the one who is part of an oppressive system upholding and benefiting structures that discriminate against Black trans folks. And the game’s intro after asking for my identity markers leaves no doubt about that.

Just like in many other games I am being given a task to “prove me (the game’s creator I suppose) wrong” as there is little trust toward me. The task at hand here is to protect a Black trans femme while travelling through “staring experiences” or burying someone’s “deadname”, i.e. the name given up by a trans person upon transitioning, among other tasks.

No matter my identity I am seeing elements of Black trans bodies and identities throughout the archive, as Brathwaite-Shirley uses images of “our hands, our feet, our hair” referring to Black trans people. She states that this way the archival elements fill up every layer of the game and the experience.

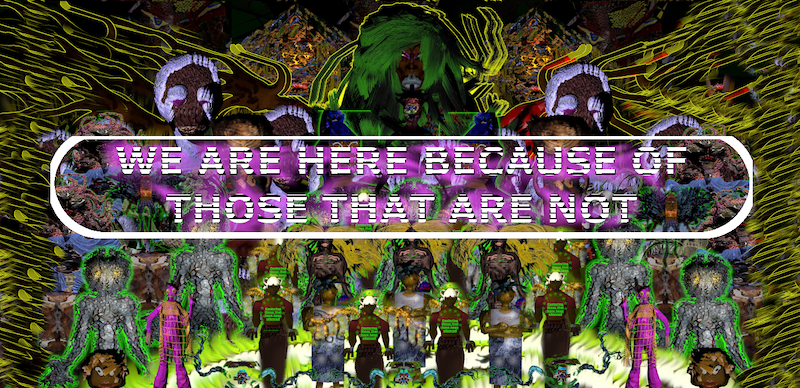

One statement in the game sticks out to me strongly:

“I wish I could dig my hand into the soil and bring back a Black trans ancestor.”

www.blacktransarchive.com after choosing to use my privileges to protect others

This ancestral focus and viewpoint is what we see both in the Black Trans Archive as well as in the Wagadu Chronicles as these seek to elevate, empower and celebrate often invisible ancestral knowledge, rituals, lives and influences and those looking for it. In an act that in my opinion focuses on rematriation rather than repatriation these to projects add to building a platform of queer Black voices to counter mainstream narratives and representations. Rematriation can be understood as “the re-socialization of cultural artefacts in a social and communal context, aspects not attained in the processes of repatriation“ and is a concept rooted in indigenous practice that I aim to explore more deeply in an upcoming post.

By following this approach both projects stand a chance at resisting what Benjamin calls the New Jim Code, “a set of methods that make coded inequity desirable and profitable to a wide array of social actors” (Benjamin, 2019, p. 161). They both do so in radically different ways. The Black Trans Archive does not want to make me comfortable but rather approaches me by holding me directly responsible for the plight of Black trans folk. And rightfully so. In contrast, the Wagadu Chronicles create a beautiful, all encompassing environment and try to change a white player’s mind through a more comfortable and enjoyable experience.

While they may differ in their approach and application of game mechanics they do both apply what Green may call a trans analytic, using the term trans* as a modifier or method of “simultaneously deconstructing and reconstructing or reimagining new possible ways of being and doing” (Green, 2016, p. 66) in this case to archiving and celebrating ancestral knowledge through a matriarchal lens, which I see here as the trans modifier.

In conclusion I believe that the two projects highlighted here, the Black Trans Archive and the Wagadu Chronicles have the potential to reduce social inequities by staying true to their mission and as such improve social development at large. I believe that if a reflective way of working with digital storytelling, the required tools and industry players is followed, that both projects can overcome potential hindrances, such a tokenism and other forms of exploitation. They are digital projects that not only bridge the digital divide of content creators in the games and digital industry but ideally uplift marginalised communities and challenge those benefiting from systems of oppression across various settings as their reach is potentially global.

DISCLAIMER:

I am writing from the perspective of a white middle-class European, queer, able-bodied, cis woman.

REFERENCES:

- hooks, bell. (1984). Feminist theory: From margin to center. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Pascal, Blaise. (1995) Pensées. AJ Krailsheimer, trans. New York: Penguin Books.

- Benjamin, Ruha. (2019). Race After Technology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Green, Kai M. (2016). ‘Troubling the Waters – Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic’, in Johnson, Patrick E. (ed.) No Tea, No Shade. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 65-82.

- Toffler, Alvin. (1970). Future shock. New York: Random House.

- Hall, Stuart. (1984), ‘The Spectacle of the ‘Other’’, in Hall, Stuart (ed.) Representation 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 215-287

- Couldry, Nick. (2008). ‚Digital storytelling, media research and democracy: conceptual choices and alternative futures‘, in: Lundby, Knut, (ed.) Digital storytelling, mediatized stories: self-representations in new media. Digital formations. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., pp. 41-60.