Let me begin with Blumer’s 1969 (quoted in Crossley 2002:3) definition of what social movements are:

Social movements can be viewed as collective enterprises seeking to establish a new order of life. They have their inception in a condition of unrest, and derive their move power on one hand from dissatisfaction with the current form of life, and on the other hand, from wishes and hopes for a new system of living. The career of social movement depicts the emergence of a new order of life.

Bulmer 1969

What does hair have to do with “a condition of unrest” that might cause so much “dissatisfaction” that one may want to establish “a new order of life”? Well, hair matters. So much so that, for my friend who is currently based in Geneva, having her hair cared for properly seems a good reason enough to get on a plane and go home to Nairobi whenever she can afford the time. A little extreme, you think? Well, renowned Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie takes the radicalism further and posits that “if Michelle Obama had natural hair, Barack Obama would not have won [the elections] … He would not have won.” The author herself was the first to acknowledge that the rather provocative assertion is “sad and seems shallow” in her 2014 conversation with Danish journalist Synne Rifbjerg. She nonetheless maintains that “hair is political”. And, in the firm but gentle straightforwardness that is distinctively hers, she rarely shies away from publicly defending this position. As a subculture of body politics, hair matters are “a powerful signifier of ethnic and cultural difference” in Adichie’s work, according to Cruz-Guitierrez (2017:245).

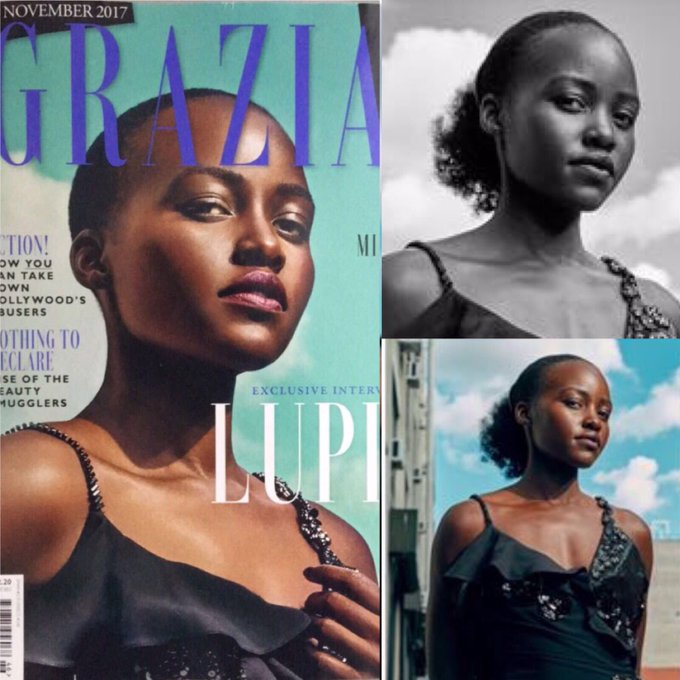

Outside of fiction, there seems to have been a proliferation of scholarly work on Black women hair in recent years. Legendary bell hooks paved the way in 1988 and Banks (2000), Byrd and Tharps (2014 [2001]), Pathon (2006), Thompson (2009), Saro-Wiwa (2012), Un’ruly (2013) and Selasi (2015) are some of the scholars who followed all the way into the 21st century. An example of texts written in more accessible language would be Emma Dabiri’s collection Don’t Touch My Hair (2019). Here, the telling of the personal and the historical intertwine in the intricate tale of black hair’s history, society’s perception of it and its linkage to racism. Three years earlier, an eponymous song produced by African-American singer Solange Knowles did not get as much attention as the singer’s outcry when a U.K. magazine did touch, or should I say, censored her hair. Hers and Kenyan actress Lupita Nyong’o’s outcry might very well have made one of the loudest protests against hair alteration. Echoes of their protest produced a commotion on the web and Nyong’o who wrote that “[t]here is still a very long way to go to combat the unconscious prejudice against black women’s complexion, hair style and texture” ended up writing one of the rare children’s book to address the issue of colourism, another aspect of body politics.

This discussion centers around what I deem #HairActivism among ordinary people like you and me, in new media, rather than in fiction, academia or Hollywood. I happen to know a number of women who enjoyed the “support, hair tips, advice and education about hair” from video bloggers or vloggers Ellington (2014:552) refers to. Consider this an attempt to understand whether this phenomenon qualifies as activism. What emerges in the second part of the discussion strongly suggests that the world of Naturalistas as we know it today would not exist, had it not been for new media. Do let me know what you think in the comment section.

From #Hairitage to #HairActivism

Research shows that, long before doing a big chop, transitioning and going natural became part of Naturalistas’ everyday jargon, hair in Africa served as a signifier of age, religion, identity/tribe, but also of marital status, wealth and rank (Byrd & Tharps 2001, Jacob-Huey 2006, Patton 2006 and Thompson 2008). This was prior to imperialism and the Atlantic Slave Trade a period during which slaves, for instance, were denied the value of hair maintenance by their White owners who claimed that African people had wool rather than hair on their heads (Byrd & Tharps 2001 and Thomson 2009). Verbal violence expressed in dichotomies such good versus bad hair, smooth and silky versus stubborn and unruly hair often resulted in physical harm as Black women set out, by hook or by crook, to tame and straighten their hair with the help of a hot comb or chemicals.

Unsurprising, therefore, wearing natural hair became an act of rebellion, first in the 1960s during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and again in the 1980s before the “third wave of hair movements” as Cruz-Gutiérrez (2017:247) refers to today’s worldwide trend. According to her, these hair movements are commonly understood to be “socio-political demonstrations that originated in the United States and [that are] directed towards visibilizing the importance of Black natural hair in processes of identity formation” (Cruz-Gutiérrez 2017:246). Blumer (1969:69) in the above definition talks about a “career of social movement [which] depicts the emergence of a new order of life.” I maintain that, when it comes to hair, Black women need a new order of life. But why?

Ever posted what you believed a gorgeous photo of yourself on social media, only to get bombarded by private messages from (mostly!) family members asking: “What’s with the hair?” You are not alone, are you? The majority of informants in Ellington’s 2014 study confessed that the unreceptiveness and, at times, condemnation towards their decision to go natural mostly came from Black members of their community when their White counterparts were not judgmental at all. This lack of self-acceptance that sometimes verges self-contempt towards one’s hair and therefore one’s genetics has historical ramifications. These women mostly come from a tradition where, for generations, women would spend hours in beauty salons and resurface their natural hair hidden under layers of synthetic hair when not directly “fixed” by means of a straightener, chemical or electrical. There is, in other words, an explanation as to why otherwise well-rounded adult women who, for the most part, positively contribute to society need “support”, “tips”, “advice” and “education” about their own hair. They talked about an “unspoken community”, some kind of a secret sorority as Ellington calls it (2014:565).

For the kinkiness of your or your friend’s or colleague’s type 3C hair to become perfectly suitable at work and not just at Reggae festivals or Brazilian summer fairs, whether styled in bantu knots or the neater sister locks, a revolution had to take place, albeit quietly. If I haven’t convinced you by now, let us try another definition, slightly altered to make my point. It is by Della Porta and Diani 1999:16 and I also found it in Crossley (2002:6):

(1) informal [hairstyling] networks based on (2) shared beliefs and solidarity, which mobilise about (3) conflictual [hairstyle] issues, through (4) the frequent use of various forms of [natural hair] protest.

Della Porta and Diani 1999

Via Self-Development on New Media

“New media is everything that is delivered digitally to you”, as my friend who co-hosts this blog rightly puts it in her latest blog. For Cruz-Gutiérrez (2017), the third wave of hair movements cannot be separated from its online ramifications, which can be taken to mean that it took Instagram, Facebook, blogging, vlogging including via YouTube and countless other channels for the wave to splash over Naturalistas in all corners of the world. A community was born, an online one, and, at least in the case of Ellington’s study, there was an increase in self-esteem among 76% of the participants thanks to communication via social networking sites. What these women mean is that they found “safe places” which, Collins (2000) describes as spaces where Black women can adequately resist hegemonic patriarchal values as well as stereotypes of Black womanhood.

When it comes to online spaces, the authors of How Society Changed Social Networks take an interesting stand. They reject the common idea that online life should be opposed to life offline. To illustrate their point, they describe a myriad of communities such as that of Chinese factory migrants whose offline life mainly consists of work and who consider their real life to mostly happen on the Chinese social media platform QQ. One school dropout, a girl, testifies that “Life outside the mobile phone is unbearable” (Miller et al. 2016:111). I struggle to imagine a world where Black women who wear natural hair would feel more alive online. That would be extreme, isn’t it? Thus, perhaps, the revolution.

In conclusion, I apply Della Porta and Diani’s definition to hypothesize that, when venturing on their natural hair journey, these women needed a solidarity network that shared their beliefs so they could “protest” against the status quo as far as their hair maintenance was concerned. If development means freedom, as Amartya Sen has suggested, some #Naturalistas seem to have attained a certain level of freedom, of self-development. Are you one of them? Did the process of transitioning feel like a (quiet?) revolution? Where you reclaiming your right to simply be? Or were you just… going natural? If you aren’t, have you, in an entirely different context, experienced online communities as a safe place? Allez, talk to me!