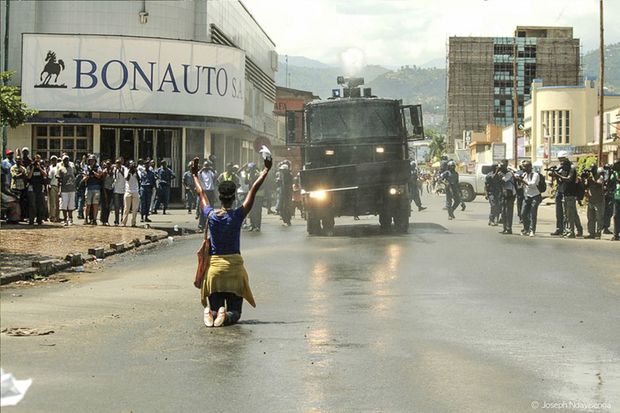

Image above: Ketty Nivyabandi kneels down in exasperation during the 13 May 2015 women-only led protests. Photo by © Joseph Ndayisenga

From leader of the first ever women-only street protests in Bujumbura, Burundi to Secretary General of Amnesty International Canada, anglophone branch

In my first blog post a few weeks ago, a discussion on #HairActivism, I mention Amartya Sen’s human capabilities approach. Increasingly, I find Sen’s perception of development to be relevant almost everywhere, regardless of the specificities of the issue at stake. More precisely, I tend to echo Martha Nussbaum who further articulates Sen’s approach as focusing on “what people are actually able to do and be… the capabilities in question should be pursued for each and every person, treating each as an end and none as a mere tool of the ends of others”. Throughout this blogging exercise, I have come to realise that, just like Nussbaum (2000), “I adopt a principle of each person’s capability, based on each person as end”. It is therefore with much enthusiasm that I introduce Ketty Nivyabandi, a person whose activism and personal development is rather atypical, as a TV5MONDE journalist put it. Ketty, the new Secretary General of Amnesty International Canada anglophone branch, is the first woman, the first African and first Black person who, moreover, holds refugee status in the country to fill the position. In 2015, Ketty’s activism was propelled into the international spotlight when she, together with some 200 Burundian women, took to the streets of Bujumbura, Burundi in protest against the late President Nkurunziza’s announcement to unconstitutionally run for a third term in office. As a reminder, Amnesty International is a worldwide movement that brings together seven million people.

This July, Ketty joined the “Dissidents and Dictators” conversation as part of a Human Rights Foundation series dedicated to exposing and challenging authoritarianism around the world. Here, she is described as having “defied police beatings, teargas and water cannons to make women voices heard” when she – together with Immaculée Hunja, Natacha Songore, Pamela Kazekare and others – organised the first women-only led peaceful demonstrations against Burundi’s President in 2015. Most of these strong women leaders live in exile today. Committed to their objective to pursue peace and firm in their conviction that sustainable peace will not be reached without the substantial contribution of women, they went on to create the Mouvement des femmes et des filles pour la paix et la sécurité (MFFPS), a movement with branches that extend beyond Burundi today.

But who is Ketty Nivyabandi, really? This blog essentially draws from the HRF conversation and attempts to summarise key ideas about what characterises Ketty, the individual and the activist.

Ketty, the Burundian

A passionate of politics and social justice, Ketty returned to Burundi just as the country was emerging from civil war, eager to “contribute to the wellbeing of my country”. Notwithstanding that he inherited a history of cyclic violence, Ketty deems that Nkurunziza had “an almost blank slate” and regrets that he missed the opportunity to turn the page on the country’s fairly recent history of impunity and violence and lead the nation to sustainable peace. For Ketty, the unconstitutional third term risked the peace Burundians had so much worked towards. Besides, it could lead back to conflict. President Nkurunziza who stayed in office for an additional five years passed away in June 2020, presumably from Covid-19 related sickness. For more on Ketty’s opinion on Nkurunziza’s 15-year presidency, read her op-ed following the passing of the President here.

On the question of whether she has mourned her beloved Burundi, Ketty vehemently answers: “My country is not dead; its nation is very much alive; its heart still beating”. In a different context, she has shared how the Burundi she knows is a Burundi of Ubuntu, the core belief in the humanity of us all; a Burundi with a culture of kindness, a culture of courage, a culture of strength, a culture of collective strength and solidarity. And, importantly for the poet in her, a country of beauty.

Ketty, the poet

On the effect of art or artivism on dictatorship, Ketty states that “art is able to penetrate the imagination of citizens and to dismantle fear”; the fear that enables dictators to exercise their power on the oppressed who feel powerless in the face of subjugation. Ketty is a strong believer in the power of art to stretch civic imagination, to stretch the mind, the heart of citizens, enabling them imagine other scenarios. While other scenarios unfold, “an inner revolution” begins and that is the critical role played by art in any oppressed society. For Ketty, true art can only flourish in a truly democratic context and everything else is performance. Poetry, in particular, evokes feelings beyond the logical, takes you places no one else can take you, so that one begins to dream and hunger for freedom.

Displace and undo that killing opposition between the text narrowly conceived as verbal text and activism narrowly conceived as some sort of mindless engagement.

— Gayatri C. Spivak,1990. The Post-colonial Critic. New York: Rutledge.

Ketty, the human rights defender currently holding refugee status

On activism as a refugee, Ketty explains that she uses her platform to pursue her fight for a more just world. She finds online activism a highly effective tool. Whether in the context of the Nobel Women’s Initiative where she held the position of advocacy and research manager or together with other Burundian human rights defenders and activists, she has successfully led or contributed to campaigns for the liberation of various human rights defenders worldwide.

For Ketty, the biggest challenge Burundians face is that of organizing. She reflects on the fact that what the current state of the country is no different from what many great nations faced decades and even centuries ago. Furthermore, she calls on solidarity among different activist movements across Africa, in the same way that dictators copy one another’s way of crushing revolutions.

Ketty’s reflection on displacement and the refugee “crisis” is that the human race has been on the go from time immemorial and that there is no refugee crisis. Rather, it is her belief that we are faced with a global crisis of empathy, a crisis of equity, a crisis of compassion, a crisis of global injustice. In Kirundi, Ketty’s mother language (and mine too!), “ubuntu” is the word that encompasses all of these values, the core belief that my wellbeing is intimately linked to that of my neighbour. I have to agree with Ketty; this is a truth that most of us seem to have lost sight of today.

In an almost premonitory speech at the 2019 International Metropolis Conference – a year before her own nomination at Amnesty International Canada – Ketty challenged the audience to change the status quo and let refugee women speak for themselves. Nobody is voiceless after all, “there are only the deliberately silenced or preferably unheard”, she added quoting Arundhati Roy. With the kind passion and vision that characterise her, Ketty expressed how she is looking forward to a UN Secretary General who is a refugee woman or a former refugee woman.

UNHCR should be led by a former refugee woman or a refugee woman. Who else knows this better than her?

— Ketty Nivyabandi, 2019 International Metropolis Conference.

Ketty, the “active citizen”

What most of us perceive as activism, Ketty sees as simple active citizenship. She compares dictatorship to patriarchy in that both instil fear in those whom they oppress and silence. Dictatorship muzzles all members of society whereas patriarchy muzzles women. She then goes on to remember her stomach literally turning from fright the first time a policeman pressed his gun onto her stomach and reaching for her fellow sisters’ arms for courage.

Ketty finds laughable the idea that women’s resistance might be a new phenomenon because “African women have resisted oppression since oppression started existing.” Similarly, police violence is not new, it has always served as a weapon for dictatorship and a tool for control comparable to the force publique, its genesis during colonial times. As she refers to Inamujandi, a Burundian legendary figure who “led rebellion against the Belgian colonial rule” in the early 1930s, Ketty recommends Dr. Yolande Bouka’s essay on “Women, Colonial Resistance, and Decolonization” where the author argues that women anticolonial resistance has been erased in scholarship.

Ketty, the mother

When asked about the rather unusual combination of motherhood and activism, Ketty is adamant that the two are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, being a mother is part of what motivates her to keep fighting for a more just world, the kind she would like her daughters to live in. To those who accuse her of having acted irresponsibly as a mother and even having put her children at risk of growing up without a mother by taking part of the 2015 peaceful protests in Burundi, Ketty’s reaction is mostly pure bafflement. The inability for some to connect the fact that when we fail to build a peaceful society, our children will not be free as adults is something she struggles to understand. Ketty could simply never look her daughters in the eyes and tell them she was powerless during this essential chapter of the country’s history. Exasperation with cyclic war drove Ketty to what she calls “active citizenship”, she says, adding “I did not want my children to have to flee or to grow up in a country that was again torn by conflict, that was again torn by poverty, by corruption. I wanted a better Burundi not just for myself but for my children and all the children of Burundi.”

Already in 2015, the World Bank estimated that Burundi was slated to become the poorest country in the world in 2030 as well as the seventh contributor to world poverty. Today, multidimensional poverty affects 74% of the population. Ketty is one of an estimated half million Burundians who fled their home, the majority of whom live in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. Considering that her dream to see a peaceful Burundi for her own children as well as all of Burundi’s children is yet to be achieved, she may have struggled or continue to struggle with feelings of failure. There is, after all, no life to look forward to in refugee camps, as Ketty eloquently puts it.

However, I choose to focus on success stories such as hers. And, by extension, I remain hopeful that for many whose lives have been turned upside down due to forced migration, theirs is or will be a story of success. Indeed, what Ketty and many who hold refugee status are “actually able to do and be… [their] capabilities”, as Martha Nussbaum would put it, has the potential to augment tremendously after they immigrate. I perceive “development” as Amartya Sen’s “capability expansion” and would therefore posit that Ketty’s own development, her choice and opportunity have expanded, undoubtedly. Ketty understands that she may not live to witness the changes she aspires to see for her motherland. As the newly appointed Secretary General of Amnesty International in anglophone Canada, she continues nonetheless to fight tyranny in Burundi and elsewhere, passionately and tirelessly so. I personally cannot imagine a better place for Ketty Nivyabandi to exercise her active citizenship, can you?

Remembering Burundi, a poem by Ketty Nivyabandi I remember you. A spark tearing the blue sky. Seeds flirting with clouds. Men confiding in stars. A song held warm and snug, in dreamy backs. Women smelling of butter. A swollen breast. The milky way. Dew quenching the splintered feet. I remember you. A dream. Kneaded with laterite and steel. Proud men, chests bursting full. Spears, hoes laying still on the moist ground. Walking, naked, to the sun. Butterfly girls. Scattering, flying. Soaking the heavens with colours. Smothered laughs. Messy laughs. Free laughs. Laughter in thousands. I remember you. Poised-people. Truth-people. Masterly people. Cracked-but-whole people. Jade, fleeing beauty. A jealous, wild, bewitching beauty. The kind to burn a prophet’s eyes... A tiny scoop of land that once dared defy the Reich. I remember you. Before your feather-words. Before your paper-sons. Before your gaping ground, your wandering children. Before your dignity in crumbs. For sale. On the sidewalks of famished boulevards. I remember you. In the furor of my nappy hair. In the ink snaking down these trembling hands. In my precious dreams, powdered with dust. In my sweats. In my screams. In my fevers. In my eyes. Dangling wide open, from the crescent moon. I remember you. Yesterday still. Tomorrow (of course). This morning. I don’t know.

For “Je me souviens de toi”, the French version of the poem, click here.