This series of articles elucidates the consequences of what limited access to information and the ever-growing spread of misinformation have on the most vulnerable groups of the society.

In the second part of this two-part series, I will dive into looking at how to ensure that vulnerable groups such as indigenous people and minorities are able to access information on COVID-19 in their own languages and with help of technology. In the first part l discussed indigenous peoples’ and minorities’ ability to access official information on COVID-19 despite limitations that have to do with a lack of adequate IT equipment or poor digital literacy skills. This second part will focus on the role of minority languages and communities living remotely in pandemic response communication.

#infodemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is accompanied by an #infodemic: All sort of information is actively spread online. It can be challenging enough to find accurate data amid all the misinformation even when the message is in your own language but what about when such information is not available in your own, minority language? As the pandemic has spread to countries with high levels of poverty, malnutrition and other disadvantages, it is crucial to ensure the life-saving information is distributed in less spoken minority and indigenous languages to ensure everyone has access to it in their own language.

Access to information limited due to language

In many cases the problem is not the lack of access to physical devices or internet connection but instead the language the message is produced in may be wrong. Where access to information is available in theory, the problem takes another kind of a feature. In Peru, for example, the national television broadcasts in Spanish for 23 hours per day, leaving only one hour for broadcasts in indigenous languages. This situation clearly depicts the overall attitude mainstream media has towards the indigenous peoples. What to do then when the information about COVID-19 may not be available in your language at all?

Unesco, in partnership with the Innovation for Policy Foundation (i4Policy) has launched an online campaign to crowdsource local openly licensed content to inform communities across Africa about COVID-19. The campaign #DontGoViral highlights the need to make sure the information on COVID-19 is culturally relevant and available in local African languages. Artists play a crucial role in sharing critical information among fans and followers as they can reach an immense audience by using diverse forms of cultural expression, including performing in their own, minority languages.

The project works in such a way that an artist creates any sort of an artistic piece, be it music or a performance, shares it on social media and tags #DontGoViral and then uploads the raw content to http://bit.ly/dontgoviral in a format that others can adapt, remix and translate.

“For the launch of the campaign, Ugandan musician and member of parliament, Bobi Wine, announced that he is openly licensing his latest hit song “Corona Virus Alert,” encouraging other artists to do the same, and inviting fellow artists and creatives all over the world to join the #DontGoViral campaign.”

Access to information limited due to remoteness

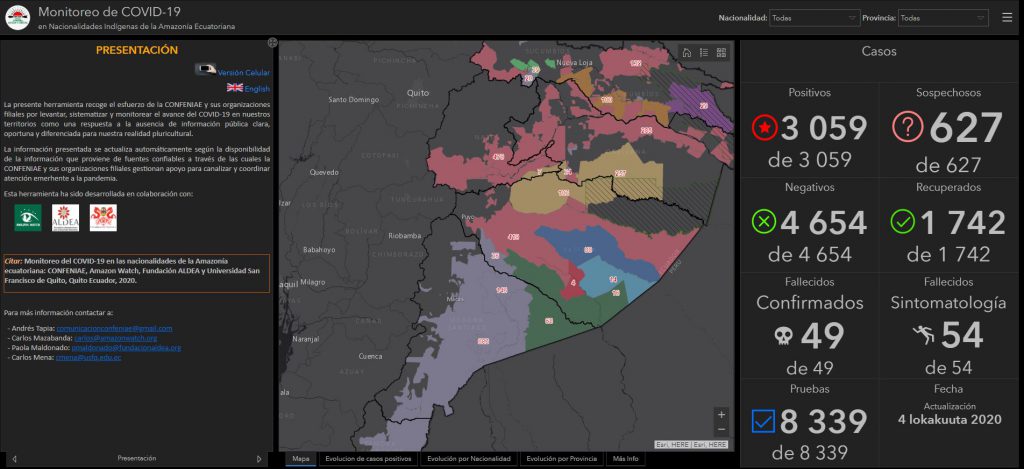

Minorities do not struggle only because of a language barrier but due to their remote location. Soon after COVID-19 pandemic started spreading in Ecuador, the Indigenous Amazonian peoples noticed that the government is not providing data specific to areas where they live in. These communities are particularly vulnerable to the disease as they already have a limited access to public services, such as potable drinking water and healthcare. This is another example of how a government is focusing its communication on the mainstream population.

To tackle the problem, a nonprofit Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (Confeniae) designed a platform that has official information on the spread of COVID-19 among Ecuador’s 11 Amazonian peoples. The platform was created in response to the government’s failed attempts to provide accurate data and official information on the spread of the virus among the indigenous, remote communities. The platform can be found online and it also has an application for cell phones, it is available both in Spanish and in English and it has a map showing the number of COVID-19 cases for each area of the Amazonian provinces and for each nationality. The aim is to use this data to coordinate health interventions in the remote areas.

“Languages matter during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they are an intrinsic part of human rights and fundamental freedoms of their users, including access to accurate life-saving information and healthcare.”