Literacy is a deeply political question. Becoming literate means being able to question the power structures and dynamics of the context in which you are living. Over the past couple of years, the concept of ‘data literacy’ has emerged as a key priority., with its potential economic and social impact and, to a lesser extent, its potential democratizing effect.

Data Revolution

The volume of data in the world is increasing exponentially. This is the data revolution: the opportunity to improve the data that is essential for decision-making, accountability, and solving development challenges.

A term that has become mainstream in the policy and development discourse since the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda called for a data revolution for sustainable development to “strengthen data and statistics for accountability and decision-making purposes”. It refers to the applications and implications of data as a social phenomenon.

But the speed at which we have been acquiring data has caused gaps in how we process and interpret it. Becoming more comfortable analyzing and interpreting data is crucial and needs to be ensured that the promise of the data revolution is realized for all.

Too often, unfortunately, whole groups of people are not being counted and are excluded because of lack of resources, knowledge, capacity or opportunity. The challenge is to avert risks, stop and reverse growing inequalities in access to data and information. How can this be done? By developing data literacy and helping communities and individuals to generate and use data, to ensure accountability and make better decisions for themselves.

Without immediate action, gaps between developed and developing countries, between information-rich and information-poor people, and between the private and public sectors will widen, and risks of harm and abuses of human rights will grow. (‘A world that counts – mobilizing the data revolution for sustainable development’ report)

Data Literacy & development: a difficult relationship

As defined by UNESCO, literacy is “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.”

The term “literacy” is much more complex in the age of data. The first time “data literacy” has been used was in the “A world that counts – mobilizing the data revolution for sustainable development” report by The Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development (IEAG) in 2015. Based on its key recommendations, data literacy should be used to break down barriers between people and data, by implementing education programs.

We do see a problem here. This conceptualization is very skilled-based and unsatisfactory. It seems a bit too narrow: a very top-down vision of data.

Despite its growing popularity as a much-needed “bottom-up” solution, data literacy is ill-defined or ambiguous at best. (‘Beyond Data Literacy: Reinventing Community Engagement and Empowerment in the Age of Data’ report)

The notion that literacy is intrinsically good has been questioned. History sheds light on how promoting literacy has been often the way to perpetuate power structures within societies, hiding behind the notion of literacy as an empowering force. Is it happening the same nowadays, in the age of data? The risk is real.

Better data, better decisions, better lives

“Better data, better decisions, better lives” is a very common concept in the development world. The data revolution discourse itself is based on the notion that what the world needs most is “more and better data”, and more people who are able to collect and analyze it, in order to make better decisions. It suggests also that bad lives come from bad decisions, and these decisions were taken based on bad data. Even if it may be partially true, we have to acknowledge that is a too simplistic causal chain. For many reasons, including polarization and data bias, the situation is more complex than this slogan implies.

The valuable lesson that can be drawn from the “Beyond Data Literacy” report is that is fundamental to keep promoting data literacy, but we need an expansion of the concept. It is more about how to “effectively empower individuals to navigate their own data/information ecosystems to produce, engage with, communicate and use data”, following human-centered approaches.

How data can enable social change

Can data enable social change, then?

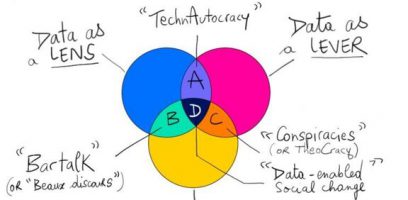

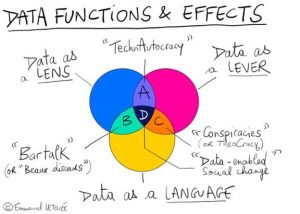

This new Venn diagram, designed by Data Pop Alliance Director Emmanuel Letouzé, suggests an alternative.

Data can be used as a better lens on the world to see and know better what’s happening. They can be also a lever of change because we as citizens can ask the world leaders to respect some standards, to achieve some objectives. We can set targets and that’s a powerful way to bring about change. But they can be also a shared language. The different stakeholders in society have to speak a common language and data can play this role, enhancing inclusion and participation.

The diagram tries to show why and how thinking about data as a lens, language, and lever of change can lead to data enabling social change. We identify three zones.

In zone A, data are only used as a lens: people know better and can make better decisions. But since it is not a shared language, it can lead to technocracy. So, decisions will be very top-down. In zone B, where data are both a lens and language, no action is taken based on that knowledge and exchange of information. In zone C, data are a shared language and also considered a lever of change. Here decisions are made but are not based on actual knowledge. They’re not leveraging data as a lens so this can lead to conspiracy, to theocracy.

It’s when you have all three together that

- you have better knowledge,

- you are willing to make decisions and take commitment, and

- when data is shared language that promotes inclusion and participation

In this “sweet spot” data can enable social change.

References:

- DPA’s Director Delivers the Keynote Address at Milwaukee Data Day 2021

- Data Literacy is the key to helping underserved communities