By Cara-Marie Findlay

A blogcast. Listen and read along as Cara-Marie Findlay reads her third and final individual blog post.

Introduction

In my first blog post, I briefly touched on how new media— like social media —is helping to facilitate overdue discussions on racism and decolonisation within Development. As an example of how new digital media can help to facilitate discussions in general, I engaged my fellow practitioners by posing a question about motivation in different online practitioner groups. For my second post, I shared the answers of colleagues from around the world, and linked them to the Time to Decolonise Aid report published earlier this year.

In this post, I discuss three ways new media contributes to the discussion around decolonising development: circulation of pertinent information through blogs and websites; community building through “writing back” on social media; and encouraging on-going dialogue about Development news and updates. In the following paragraphs, I share specific examples of each of the three contributions. I include a brief look at some of the limitations of new media in the decolonising development discourse. Finally, I conclude with my own reflections on my experience writing this blog series.

Key Assertions

In the context of this post, new media, refers to the “decentralization of channels for the distribution of messages…an increase in the options for audience members to become involved in the communication process, often entailing an interactive form of communication; and an increase in the degree of flexibility for determining the form and content through the digitization of messages” (McQuail, 1994 as referenced in Lievrouw & Livingstone 2002, p. 3). While decolonising development speaks to “the process of deconstructing colonial ideologies regarding the superiority and privilege of Western [or Eurocentric] thought and approaches” (Peace Direct, 2021, p. 13).

Before going any further, it is important to note that as practitioners we are “doing development in an increasingly digitalised context,” or to state it another way, we are engaged in “Development in a Digital World” (Roberts, 2019). What does that mean? It means, in our current setting, many aspects of social and economic life have become datafied—from social interaction to shopping habits—and it would be remiss of us to ignore the consequences this has for international development.

Three Contributions

Circulation of Pertinent Information

One of the consequences of doing Development in a Digital World is an added digital layer to humanitarian work. Mark Duffield refers to this digital layer as “cyber-humanitarianism” or “the increasing reliance [on] remote and smart [inter]Net-based technologies” (Duffield, 2013, p. 4) for the delivery of, and access to, Development aid. Technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality are rapidly reshaping the humanitarian space. Thus, Development agencies and practitioners need to understand the trends, emerging issues, and potential harm we are buying into.

Fortunately, new media, such as blogs and websites, can offer a way to circulate pertinent information that looks critically at these emerging issues. Including, how cyber-humanitarian technology can, and has, helped to re-entrench neocolonial ideas in Development (e.g. modernisation). Blogs and websites also offer the possibility for significantly increasing the reach of the writer and/or publisher, thus attracting a wider audience.

For example, U.S. media watch group FAIR (Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting) has been around since 1986. FAIR’s weekly radio show CounterSpin has addressed topics such as racism and technology. ‘Black Communities Are Already Living in a Tech Dystopia’ is a Counterspin episode that featured an interview with Ruha Benjamin, the author of Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. In the interview, Benjamin articulates that technology “is not, in fact, objective in the way we are being socialized to believe” (Jackson, 2019). A view that challenges the prevailing Western ideology that technology is neutral, and an important fact for us to consider as practitioners engaged in cyber-humanitarian work.

FAIR’s website makes it easy to find and listen to previous episodes, including the one aforementioned; and for those who would rather read than listen, FAIR includes a typed transcript of the interview on the episode’s webpage. The FAIR website makes it convenient to share an episode’s page on social media or to email it. It is safe to assume that without a website, an email list, and shares on social media, FAIR would not be able to reach “an international network of over 50,000 activists” (FAIR, n.d.). New media has made it possible to amplify and circulate serious points, such as “how the implicit biases of the larger society can affect technological outputs” (Findlay, 2021). In turn, amplifying and circulating questions around the effectiveness of cyber-humanitarianism; and the need to decolonise our understanding and use of ICT4D (information communication technology for development). New media also made it possible for a U.S. organisation to reach an international audience.

Community Building on Social Media

New Media (particularly, social media) also presents an opportunity for virtual communities to be formed around the postcolonial concept of “writing back;” that is “responding to colonial legacies [or] challenging colonial cultural attitudes” (McEwan, 2019, p. 31). New media allows people situated in the Global South, who are often “rendered voiceless” to “write back back from the margins” (McEwan, 2019, pp. 22, 57) and contest the ‘lingering and debilitating modes of thought and action’ in Development (Myers, 2006 as quoted in McEwan, 2019, p. 33). Modes that would silence or ignore the experiences of those who were previously colonised, and who are now receiving Development assistance from primarily Western humanitarian agencies.

These virtual communities may come in different forms. For example, there is the Black Women in Development Facebook group, which allows Black women from around the world to share their Development experiences (the good, the bad, and the ugly) while also enabling them to be a resource to one another (e.g. sharing job opportunities, offering advice, etc.).

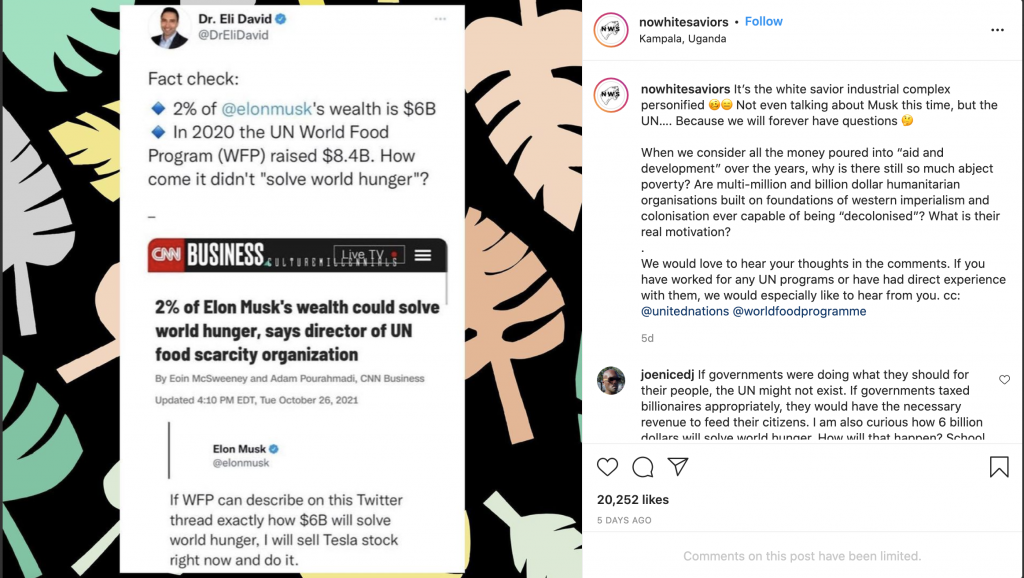

Another example of a virtual community centered around writing back is the No White Saviors (NWS) instagram page. NWS is an advocacy campaign, led by four women (three are native Ugandans, the other is described as a “white savior in recovery”), dedicated to directing the Development and Aid sectors towards an anti-racist future. NWS uses their instagram platform in particular to: highlight problematic examples of Development and aid practice; issue calls to take online and offline action; and to spotlight and support those they believe are doing Development right. Their instagram posts often feature long captions explaining the significance of the corresponding image and a call to action urging their community of 877K followers to respond to the post in some way. As in real life, people who are a part of, or who visit, this virtual NWS community “use words on screens [i.e. their comments on a NWS post] to exchange pleasantries and argue, engage in intellectual discourse…exchange knowledge, share emotional support, make plans, brainstorm” etc. (Rheingold, 1993 as quoted in Lievrouw & Livingstone 2002, p. 7). The NWS instagram community has united people who are physically separated (many situated in the Global South and many in the Global North as well) around the common belief that the Development sector needs to be decolonised and reformed to ensure a better, more equitable, Development.

Encouraging On-going Dialogue

Another way new media contributes to the discourse of decolonising development is through its ability to generate dialogue and offer audience members an opportunity to react and respond in their own time. Sometimes these responses are close to real-time (for example, replying to breaking news on Twitter); and other times these responses may come weeks, months, or even years laters (for example, leaving a comment on an older blog post or online news article).

New media has made it easier for anyone with access to the internet to collect, disseminate, and react to news; in this case, news regarding racism in the Development sector. For example, in September 2020, The New Humanitarian published an article, “Readers React | Racism in the Aid Sector and the Way Forward” composed almost entirely of reader comments to a series of different New Humanitarian articles on “how the Black Lives Matter movement is reverberating through the aid sector.” The Readers React article shared aid worker/Development practitioner experiences of racism in their humanitarian work, in their own words. The article also includes a link to a Google form where readers can continue to add and share their own experiences with racism within the sector, even today, more than a year later. It is important to note that the series of #BlackLivesMatter articles launched by The New Humanitarian in June was in direct response to the murder of George Floyd in the U.S. which sparked racial justice protests around the world.

Limitations of New Media

While new media has, and can, contribute to the decolonising Development discourse it also has its limitations. These limitations include the circulation of fake news or other inaccurate information, and the censorship (or “shadowbanning” – blocking a social media account’s content so that it is less prominent or visible to others) of voices that diverge from dominant Development discourses.

Additionally, the ease of which a user can choose to engage (or not engage) in a virtual community is also a reason virtual communities must be considered more unstable than “‘real-life’ or offline communities;” since “individuals [and organisations and campaigns like NWS] can become active and prominent quickly, and just as quickly disappear altogether” (Lievrouw & Livingstone 2002, p. 7).

Furthermore, it is still unclear how much influence new media has (if any) on the existing levers of power in Development—policy, practice, and scholarship.

To quote one of my professors, Tobias Denskus, and his esteemed colleague Andrea Papan:

“There is little evidence that blogging and its learning processes influence macro-policy making [in Development]. Organisational rituals and artefacts such as global summits, policy papers, and the powerful role of international organisations in research, policy, and practice still shape the [dominant] discourse[s]. Blogs can help to expose these rituals and continue to work towards an alternative virtual learning space that reflects new and diverse voices…and can help introduce reflexive writing to more people.” (Denskus & Papan, 2013, p. 466).

Though this quote is in reference to blogging, the sentiment can be applied to all forms of new media.

Another clear limitation is the lack of access to new media for peoples in the Global South. Many individuals situated in the Global South still do not have access to an affordable or stable internet connection that would allow them to engage and participate in these forums, which limits their important and needed contributions to the discourse on decolonising development.

Conclusion

This blog series has allowed me to gain a deeper understanding of how useful a tool new media can be in adding to the discourse around decolonising development. Interestingly enough, new media is a term that has been used since the 1960s and 1970s by researchers investigating the implications of information and communication technologies (Lievrouw & Livingstone 2002, p. 2). And the Eurocentric thought and approaches that have led to, and invisibilised, racism within the sector is as old as Development itself. Thus, for me, questions still remain. Is new media capable of influencing transformative change within the sector? If yes, then how? Especially, when one of the key features of new media is the decentralisation of channels. The levers of power within development remain very much centralised and entrenched within the Global North. Since this is the case, as practitioners we must seriously question whether those who are currently at the helm of these levers of power even desire to see decolonial transformation within the sector. More than that, as practitioners, we must ask ourselves if we truly desire a decolonised Development which may in turn oust us from being positioned as “experts”.

As previously mentioned in an earlier post, I started a consulting company to help ensure that more underrepresented and impacted peoples would be able to participate in the Development dialogue and process taking place. Thus, although this academic exercise is coming to an end, I (along with my colleagues at my consulting firm) will continue to explore these critical questions and engage the broader public on topics in Development through the company blog.

My hope is that as practitioners we will continue to engage in reflexive practice and create space for, and embrace, difference within this field. Only when we take into account and value our different experiences and ways of knowing, will we be able to truly come together and discover the best and most effective ways to solve the world’s biggest challenges.

References

Denskus, T. & Papan, A. (2013): Reflexive engagements: the international development blogging evolution and its challenges, Development in Practice 23:4, 435-447.

Duffield, M. (2013). Disaster-resilience in the network age: Access-denial and the rise of cyber-humanitarianism (DIIS Working Paper 2013:23). Copenhagen: Danish Institute of International Studies (DIIS). Retrieved from: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/122292/1/782863604.pdf

Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR). (n.d.). What’s FAIR? Retrieved from: https://fair.org/about-fair/

Findlay, C. (2021). On C.L.Ai.R.A. and Tech Bias in the United States. Findlay House Global, 14 September, retrieved from: https://peoplecentreddevelopment.com/pubs/2021/on-claira-and-tech-bias-in-the-us

Jackson, J. (2019): Black Communities Are Already Living in a Tech Dystopia (Links to an external site.), Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting, 15 August.

Lievrouw, L., & Livingstone, S. (2002). Handbook of new media. SAGE Publications, Ltd, https://www-doi-org.proxy.mau.se/10.4135/9781848608245

McEwan, C. (2019). Postcolonialism, decoloniality and development. Routledge.

Peace Direct (2021): Time to Decolonize Aid-Insights and Lessons from a global consultation. London: Peace Direct.

Readers React | Racism in the Aid Sector and the Way Forward. (2020). The New Humanitarian. Retrieved from: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2020/09/11/racism-in-humanitarian-aid-sector-Black-lives-matter

Roberts, T. (2019). Digital Development: What’s In a Name. Appropriating Technology. http://www.appropriatingtechnology.org/?q=node/302

hat was once shrouded in darkness, has now come to light. In recent years, and thanks in large part to new media like social media platforms, there have been more (and overdue) discussions about racism and the need to decolonise development. Undoubtedly, these conversations can be uncomfortable and unsettling for many who are used to the old way of Development. But Development is changing (and must change!) in order to be transformative and effective.

hat was once shrouded in darkness, has now come to light. In recent years, and thanks in large part to new media like social media platforms, there have been more (and overdue) discussions about racism and the need to decolonise development. Undoubtedly, these conversations can be uncomfortable and unsettling for many who are used to the old way of Development. But Development is changing (and must change!) in order to be transformative and effective.