In my last post I wrote about online activism as a tool for seeking social change. I wondered, among other questions, to what extent we recognise power relations in these virtual spheres and how we unconsciously perpetuate them. Always from my privileged position as a young white European woman and within the context of this blog (wich aims to help us who post and our readers to find new narratives not mainstream in the Global North).

The truth is that my interest in writing about this stems from my continuous doubts about my own use of social media, both in my professional role as a communicator in the field of international cooperation and development, and in my non-professional role, in which I visit platforms such as Instagram or Facebook on a daily basis.

I often find myself in the position of sharing or not sharing certain contents that can be categorised as activist on issues that are undoubtedly extremely important, and yet 99% of the time I end up not sharing them. It would also clarify that although I use these social media networks on a daily basis, I am not very active in posting content of any kind (not so in my professional facet).

My problem with this is that my entire Instagram feed seems to tell me that not sharing anything about a certain cause is tantamount to not supporting it, to not wanting to take notice, to not caring about the situation of women in the world, poverty or racism. I mean, if the news in Europe is filled with headlines about the arrival of the Taliban in Afghanistan, and my Instagram is filled with infographics listing facts about the repression women suffer under Taliban command (almost like a trend that will fade away in days or weeks), when I choose not to share anything, the power that peer pressure has over me and my online identity formation makes me feel bad, because after all, if all the effort it takes to “do something” is to click a button and I chose not to, what kind of person am I?

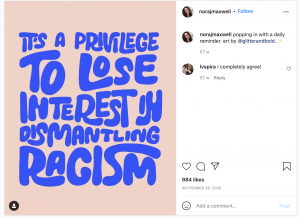

But the truth is that, on the contrary, sharing a post denouncing the police brutality suffered by black people at the very moment that #BlakLivesMatter goes viral may seems illegitimate to me personally. It feels wrong maybe because I don’t think I have the necessary knowledge about that reality Black people is fighting against, I have never experienced it because my place in the world is privileged, and perhaps I wasn’t even fully aware of the extend of it it before a hashtag went viral. My decision not to speak out (and I only mean not to perform social media activism) is because at a time when others who do know are gaining unprecedented visibility to share their knowledge and denounce their conditions in society via these platforms, I believe my role is to read and inform myself, learn how to be more aware of how my privileges exist because others suffer the oppression and institutional violence that I do not, and to understand my responsibility and my options to change the things in my daily life or professional actions that will actually contribute to changing that reality.

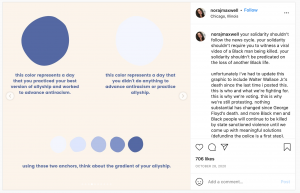

Because if I press the share button, who am I saying what to? What am I contributing with to change the reality I am denouncing? Am I not just adding more noise and subtracting visibility from others who know and have more right to speak out than I do? This is the case of the discussions arised after #BlackOutTuesday. In brief, posting certain contents seems to me usually a simple act of virtue signalling, “defined as a social or political stance shared by someone on social media with the hope that other like-minded individuals will commend the person who posted said stance for their sense of morality or decency” (McClanahan 4, 2021).

However, what if I’m once again making use of my privileges by staying “quiet” when I could be doing better by disseminating crucial information?

In truth, all this personal reflection is just my way of explaining you why I am interested in using this blog to write about topics like digital allyship and the role of us, white citizens in the North, in digital anti-racist activism. How to practice a benefitial allyship in the current social media scenario? Is that possible at all? Just a quick search on Google will show you countless articles and videos with “tips for being an ally” and also some other crucial arguments against this idea, such as Ernest Owens’ words in “White People, Please Stop Declaring Yourself Allies”.

What does it say to the humanity of Black people that white people still get to play both the hero and the villain in their trauma?

Owens, 2021

Despite my doubts about how to best act from my priviledged position and even about the extent to which these new media can serve as tools to fight the same racist, patriarchal and capitalist system that controls them, I believe that in order to challenge the colonial structures that shape our societies, it is crucial to continue to reflect on and reveal our own privileges, including those linked to our online identities. In this regard I agree with McClanahan when, after studying the most common mistakes made by white allies, she concludes that “white allies need not only to recognise their shortcomings, but also to know how to prevent them from occurring in the future as well” (16, 2021).

So in my next post, coming soon, I want to explore these issues on digital allyship further. For that I would like to count with your opinion. Just by answering the questions I am posting on our Instagram’s stories you will help me enormously. And if you prefer, you can leave your answers to the same questionnaire and any other comments here below.

Here are my questions for you:

- Do you believe that sharing content on social media is a “good thing” you can do to fight for social justice?

- Do you regularly use social media for this purpose?

- Do you identify as a white ally?

- Did you actively participate in the #BLM movement on social media? Did you participate in any other BLM action in your country?

- When you get involved in a social justice issue by using a hashtagh, do you research who originated it, when and how?

- When you repost information from others on your social media, do you fact-check? Do you check the who is the content creator/ source?