The Digital Divide

It is an undeniable fact that the new ICTs are now virtually everywhere and they are affecting our lives in unprecedented ways. And as almost everything in this world, they have both positive and negative aspects. For the former we can mention the belief and hope that they can help solving the various societal problems within the scope of the international development goals, such as poverty and education to name a few (Heeks, 2018, p.2). For the latter, we can claim that ICTs have done nothing towards a more just society, and in a way, they have even increased inequality (Unwin, 2017a, p.1). In this post we will focus on the negative aspects and the perceived inequalities of ICTs in development (ICT4D), and we will discuss the modern issue of the ‘Digital Divide’, as it is a fact that even today “3,7 billion people, the majority of them women, and most in developing countries, are still offline” (UN, 2021). We argue that we need to reflect on Paolo Freire’s famous book and phrase, ‘The Pedagogy of the Oppressed’, and bring him and his theory in today’s digital reality. By that, we suggest that, today, and in this digitally connected world, we need a rather ‘Digital’ Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

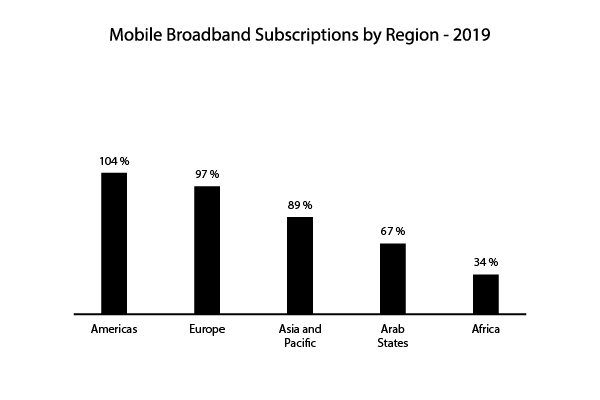

Source: ITU – Measuring Digital Development 2019

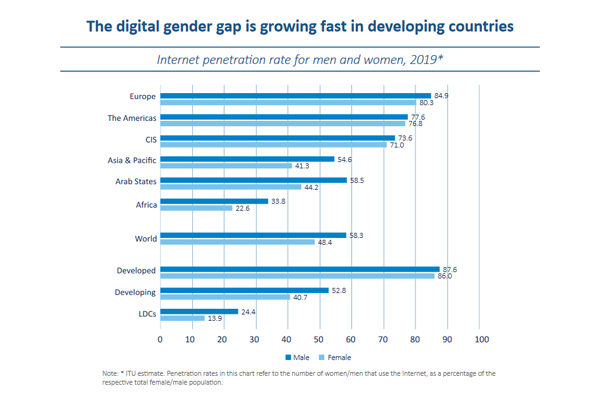

After 50 years from the writing of Freire’s modern classic book, unfortunately, within the international development sector, we still talk about tackling the social issue of inequality, and we still have in our globalized societies the social roles of the oppressors and the oppressed. But the bad news is that to this old-school relationships of the oppressors-oppressed that Freire talked about, it was added a new, modern type of social inequality, that is defined by the degree and quality of access of the individual, a social group, or even a nation and a continent to the new ICTs. Additionally, there are also concerns about the degree of digital literacy of the people, or their lack of, which defines their ability to comprehend and use effectively a new technology in order to solve a societal issue. This new form of digital inequality is called ‘The Digital Divide’, and according to Heeks (2018, p.17) it is “the gap between those who has access [to the ICTs] and those who does not”, and it can be found between urban and rural citizens, between developed and developing countries, between educated and uneducated people, and of course between genders (Steele, 2019). Indeed, if we draw again from Heeks, the ‘Digital Poverty’ affects all these people that live in a poor country, while those who take advantage of the benefits of the use of ICTs are mostly “men, younger citizens, ethnic majorities, those without disabilities, and urban dwellers” (Heeks, 2018, p.88).

Source: ITU – Measuring Digital Development 2019

In that sense, the people that stay behind in this digital (r)evolution, are less privileged than those who are using successfully the new technologies, and thus, this situation makes us understand that the state or process of ‘dehumanization’ that Freire talked about is still relevant. According to Freire (2000, p.44), dehumanization “is not a given destiny but result of an unjust order that engenders violence in the oppressors, which in turns dehumanizes the oppressed”. In the case of our Digital Divide, we could argue that those who are excluded from the benefits of the use of ICTs, and still face poverty and inequality, have the role of the oppressed, and consequently, the role of the oppressor goes to the stakeholders that design development projects and “think about and implement ICTs policies and practices” (Unwin, 2017a, p.2). In fact, they must be convinced to change their mentalities and ways of thinking and acting within the development sector, in order to allow the world’s poorest and marginalized to be included as beneficiaries of the new technologies (ibid., p.2), and thus to be liberated. Indeed, that is what Unwin (ibid., p.14) claims to be the modern approach that sees ‘development’ only for economic growth, that at the end, it results in even more poverty and inequality, and thus, the dehumanization of the poor. Consequently, that is why the stakeholders of the ICT4D projects, as the decision makers of that type of development, can be seen as the modern Freirian oppressors whose decisions dehumanize the oppressed. Of course, the word ‘violence’, that Freire uses as a unifying force between the oppressors and the oppressed, may raise some readers’ objections, but nevertheless, violence can have many faces, and it does not have only to be a physical one. It can have other forms, like economic, political, and above all, psychological, which can all have material consequences in the lives of the poor.

Furthermore, it is interesting to mention the concept that Heeks (2018, p.90) proposes as the Value Chain dimension of the Digital Divide, that is various categories that the people, for some reasons, fail to use the new ICTs. For instance, the Divide might be a result of the lack of general availability of the technology to an area (Availability Divide). Or it can be the case that the technology it is physically present, but for various reasons, some people or social groups do not have access to it (Accessibility Divide). Continuously, there is the degree of the adoption of an available technology within a society, that can be affected by the individuals’ income (Adoption Divide). And finally, if a technology is available, accessible, and the people adopt it, we can still have a divide in the actual application of it, based, for instance, in gender and other related factors (Application Divide).

With all of the above in mind, and around the modern needs for a Digital Pedagogy of the Oppressed, one could wonder, how can the vast number of people that are unaffected, or even they are affected negatively, by the ICTs become beneficiaries of the technological advances of our modern world? According to Unwin’s (2017a, p.22) critique on the instrumentalist perspective of ICTs, there is no an inherent power to technology that by definition can help the poor and marginalized people. Instead, in order for technology to increase its possibilities to do good and to eliminate the Digital Divide and the related inequalities, there must be a mental change in those who design and develop technological projects in the development sector, be it governments, civic organization etc., to work ‘with’ the poor and not ‘for’ the poor. (Unwin, 2017b, p.3). That fits perfectly with the participatory model as it was expressed and practiced by Freire, and as Tufte (2017, p.23) claims on that regard, the social change could be achieved by implementing approaches in the development field that are bottom-up, and have as a focal point the poor and marginalized citizens by actively listening to them during the whole development processes, from the problem definition, to the designing of the solutions, up to their actual implementation. And that applies also to the use of ICTs in the struggle for social change. Indeed, as Unwin (2017b, p.4) points out on the same Freirian manner, there must be a radical and profound change in the focus and goals of the use of ICTs, that is, away from the economic growth and towards the reduction of the perpetuated modern types of inequality, as the latter are related with the Digital Divide.

Do not forget to follow us on Instagram and Twitter!!

REFERENCES

Freire, P., (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. NY, USA: Bloomsbury Academic.

Heeks, R., (2018). Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D). Oxon: Routhledge.

Steele, C., (2019). What is the Digital Divide?. Digital Divide Council. Retrieved 9 October 2021, from http://www.digitaldividecouncil.com/what-is-the-digital-divide/.

Tufte, T., (2017). Communication and Social Change : A Citizen Perspective. Oxford: Polity Press.

Unwin, T., (2017a). Critical Reflection on ICTs and ‘Development’. In Reclaiming Information and Communication Technologies for Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

UN, With Almost Half of World’s Population Still Offline, Digital Divide Risks Becoming ‘New Face of Inequality’, Deputy Secretary-General Warns General Assembly | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. Un.org. (2021). Retrieved 10 October 2021, from https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/dsgsm1579.doc.htm.

Unwin, T., (2017b). In the Interests of the Poorest and Most Marginalized. In Reclaiming Information and Communication Technologies for Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.