We already talked a lot about the potential harms of digital technologies and how these factors impact populations, humanitarian actions, volunteers, and the field of development itself. The dissemination of (false) information is another element of the ICT debate. While news has the potential to reach everyone, one way or another, its implications on different communities are varied. In the current COVID-19 outbreak, the lack of appropriate risk communication and community engagement fail to counter social stigma and could reinforce health inequalities.

What can we see from previous “virus communication”?

During the Ebola outbreak in 2014, a study compared news coverages in the USA and the UK with West African newspapers. While articles in West Africa highlighted the broader implications of the outbreak, the Western press concentrated on limitations of the African continent, resorting to ancient stereotypes about the continent to make sense of the situation. The whole outbreak was presented as a distance issue with little coverage until once two infected health care workers returned from Africa. How elite press portrays an event contributes to how public opinion about such event is shaped as well as how false beliefs emerge, spread, and become entrenched within communities [1].

In South Africa, AIDS denialism was institutionalized at the highest levels of government which significantly impacted public health policies and claimed to cause 300,000 deaths due to the failure to accept the use of available ARVs [antiretroviral therapy] to prevent and treat HIV/Aids in a timely manner[2]. At the global level, regardless which hemisphere of the globe we are talking about, in the early days of the global epidemic, even the pure suspicion of positive HIV infection could generate exclusion by friends, family, employers and by the society at large. The parallels with regards to the coronavirus are striking, both in terms of fear and ignorance.

When infodemic meets pandemic

The extent of infection and restrictions varies from country to country, but across the world, we all face the same thing: a high degree of uncertainty. The economic and existential uncertainty along with the angry and destroying communication have omnipresent consequences. Uncertainty is impacting how people are dealing with each other, how they are judging news and how they are comprehending this new reality. The overabundance of information is not a new phenomenon, as a result of the digital revolution, old regime [health information singlehandedly decided by news organizations, medical associations and health institutions]has been transforming to a large-scale production, distribution and consumption of health information[3].

“There are no sources that are unanimously considered to be legitimate that monopolize knowledge and truth about virtually any health issue. […] Groups and individual citizens have plenty of opportunity to question, tweak, and misinterpret established biomedical knowledge3.”

Not everyone starts on an equal chance of survival. Not everyone gets help.

Not everyone has a strong lobbying power behind them, not everyone has several monthly reserves, a solid parent company background, a billionaire owner. And not everyone accesses and comprehends information in the same manner. And as a plus, there is a new appearing from of “virus harassment” shaming, humiliating, hurting those who caught the infection, or mocking, excluding, verbally abusing those who have a different opinion about the spread of the virus.

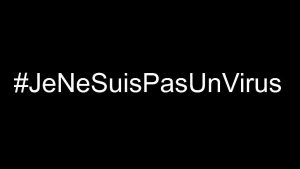

Disinformation propagated at the institutional or federal government level preserve power and undermine already marginalized groups (e. g. Black communities have been blamed for higher fatality rates among Black populations), and inequality-driven mistrust spread among communities that have been made vulnerable by historical and ongoing structural inequities[4]. Structural racism could mean disproportionate implications of the pandemic on black, Asian and minority ethnic groups.

Along with racist claims, we have also seen several incomprehensible political decisions and advice.

Donald Trump said that China must be held accountable for unleashing the Covid-19 virus on the world in a pre-recorded message to the UN General Assembly.

Thanks to Trump’s belief (although it is a very complex question, indeed), the USA is currently on track to leave the World Health Organization (in a middle of a pandemic!) which could bring very serious consequences.

Or remember when Trump suggested injecting disinfectant as a treatment?

People’s deaths have been caused by false news.

Researchers say there have been at least 800 deaths in the world caused by dangerous “good advice” appearing on such social sites, whose lives could not be saved after drinking a disinfectant because they read that it also kills the virus from the body. 5876 people were hospitalized for the same reason and at least 60 people were blinded because they drank methanol to prevent the disease. Facebook, Twitter, and online newspapers have been identified as the best platforms for monitoring misinformation and dispelling rumours, stigma, and conspiracy theories among the general people[5].

While the overall management of previous global epidemics and the current pandemic shows obvious evidence of structural stigmatization and misinformation, it also presents beneficial public health policies and community actions once social determinants of health are considered.

While several global organizations have provided guidelines on addressing social stigma or risk communication, due to technological inequalities these initiatives cannot reach everyone at a global scale. Furthermore, the lack of trust for governments could make it harder for communities to understand and follow measures. In the case of COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need for anti-racism education as well as care for marginalized populations in which volunteers could play a key role. As a case study shows, technology and digital platforms are helpful, but they often exclude some parts of the population (lack of digital literacy, language barriers, the question of accessibility, etc.), thus, digital communication does not provide a sole solution. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of local actors and volunteers, as well as the need to empower them as they are often the ones on the ground before, during, and long after a crisis is over[6].

[1] Duru A. The 2014 Ebola outbreak: narratives from UK/USA and West Africa media. Journal of International Communication. 2020;26(2):1-16.

[2] Boseley S. Mbeki Aids denial ’caused 300,000 deaths’. The Guardian. 26 November 2008. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/nov/26/aids-south-africa [Accessed 27 October 10].

[3]Waisbord S. Fake health news in the new regime of truth and (mis)information. Reciis. 2020;14(1).

[4] Jaiswal J, LoSchiavo C, Perlman DC. Disinformation, Misinformation and Inequality Driven Mistrust in the Time of COVID 19: Lessons Unlearned from AIDS Denialism. 2020; May: 1–5. Available from: doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02925-y .

[5] Md Saiful Islam Md, Sarkar T, Khan SH, et al. COVID-19–Related Infodemic and Its Impact on Public Health: A Global Social Media Analysis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020;103(4): 1621 – 1629. Available from: doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812.

[6] Ravelo JL. The community engagement lessons being used to fight COVID-19. Devex. 15 April 2020. Available from: https://www.devex.com/news/the-community-engagement-lessons-being-used-to-fight-covid-19-96969.

Photo Credit: Euronews