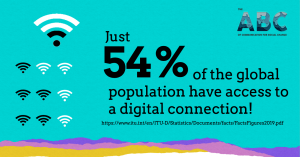

The Covid-19 pandemic has completely reshaped the way we do our jobs, how we stay in touch with our family and friends, how we learn, shop, bank and a multitude of other activities that we might not traditionally have done online. For the 54% of the global population with access to a digital connection, this leap forward has been a critical lifeline. For example, I am fortunate that I can now chat with my grandma on Zoom, something I never thought would be possible. Technology is playing an important role during this effort to save lives, including by spreading public health messages, helping us stay productive and connected, and increasing access to education and healthcare.

From AI, to sterilizing robots, to rapid developments of new technology being reappropriated in ways we have never seen before, we have seen organisations and businesses turn to technology during the Covid-19 crisis, as well as governments adopting it as part of their national response. For example, the U.S. government is in active talks with Facebook, Google and a wide array of tech companies and health experts about how they can use location data gleaned from Americans’ phones to combat the novel Coronavirus, and the Chinese government has also used phone tracking to control the outbreak. The UK government has also attempted similar technological solutions, including the Track and trace app, which aims to alert people when they have been near someone who has tested positive for coronavirus, allow people to check their symptoms, try to book a test and ‘check-in’ to places they visit using a QR code system. The ‘track and trace’ method has been part of the UK government’s response since the beginning of the outbreak, along with other digital solutions like asking citizens to book medical appointments online, conduct medical consultations digitally, and acquire prescriptions electronically, but things haven’t always gone to plan.

App-ropriate solutionism?

According to Wired, the NHS track and trace app ‘aims to automate the human process by using your smartphone… The process involves a person who is infected recounting their movements and activities to build up a picture of who else might have been exposed.’ The expected £35 million for this app demonstrates that a lot is expected from this technology, and also that a lot is expected from citizens, as well.

The idea that an app can help to tackle a public health crisis that clearly must be tackled collectively is, of course, very enticing, but for the app to stand a chance of being effective it needs to be used by as many individuals as possible.The app is currently still not mandatory, therefore it is no surprise that ministers have resorted to using peer pressure to encourage downloads (a tactic that has so far been successful during the crisis, but seems to be drastically waning as the government continually fails to lead by example). This delegation of responsibility from the government to the individual through technology is what Evgeny Mozrov calls ‘solutionism.’ In identifying ‘the emergence of these highly privatized market-based solutions that work at the level of the citizen and not at the collective,’ Mozrov also recognized that ‘more and more, we see problems as failures of the individual’.

Effectively demonstrating this strategy, health secretary, Matt Hancock, even went so far as to claim that in failing to download the track and trace app, we would be failing to do our ‘civic duty,’ and failing to ‘help to save lives,’ despite the efficacy of the app being called in to question because of its’ inability to reach the 80% target required to limit infections from spreading. By delegating responsibility to the individual, Hancock is removing the ability of citizens to ask big structural questions about how the response ought to be reformed, for example the other aspects of the UK government’s response (reports show they failed to test efficiently in the first place, and what exactly IS the lockdown policy right now?), coupled with the austerity measures – primarily in the form of deep spending cuts with comparatively small increases in tax – implemented by the government that have seen inequalityreach levels last seen in the 1920’s.

Austerity vs equality

It’s no coincidence that illness and death have been concentrated among vulnerable groups, including the elderly, those living with chronic disease, people from black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, and those who have been working in frontline public services, from health and social care to transport, food production and distribution. What Hancock and the other government ministers have failed to acknowledge here, is that since 2008, the UK government have continued to promote policies that have led to entire groups of people who associate the healthcare system with the fear of‘immigration raids at their home, with a risk of being put into detention, separated from family and loved ones, and maybe even returned to an unsafe country. Other marginalized groups such as ‘undocumented’ migrants also pose an obvious threat to public health, given the continued use of NHS data in immigration enforcement.

According to Doctors of the World:

In 2017 the UK Government made a formal agreement to use NHS records to track down people whose asylum applications had been refused and undocumented migrants. NHS Digital, the body that holds medical records in England, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Home Office allowing immigration officials to request patients’ non-clinical information (including home address).

The government have created an environment where these people are ‘too afraid to share their personal information with the NHS,’which outweighs their feelings of obligation to ‘do the right thing.’

Among the many other barriers to healthcare that pose a threat to the success of the track and trace app, digital inclusion should certainly be at the forefront. According to Helen Milner, Chief Executive of the Good Things Foundation, a UK charity set up to make the benefits of digital technology more accessible. Health inequality has worsened in the past 10 years, and digital exclusion plays into that trend. “There’s a massive overlap between digital exclusion and social exclusion, and then social exclusion and poverty, and poverty and health inequalities.”

The lockdown strategies in the UK prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic including the app, digital appointment systems, online consultations and electronic prescriptions that are not rapidly accessible to all of the population will inevitably lead to health inequalities. The inability of some of the UK population to pay for broadband or mobile data

(exacerbated by the closure of community and voluntary sector organisations that usually provide this), as well as lack of access to technology, including broadband and smartphones, and lack of knowledge and digital skills to be able to access the app, may all reduce the effectiveness of the app as an intervention.

Big data and Covid-19

Mass surveillance and a risk to privacy. Fine balance. Could very easily turn into a way to track citizens. Will they give back the power?

According to Amnesty International, government’s rushing to expand their use of technologies to track individuals in the name of responding to Covid-19 have the ‘potential to fundamentally alter the future of privacy and other human rights.’ Long before the pandemic, we saw ‘governments armed with databases who found ways to continue optimizing the logic on which they run without posing questions about reform’. It is now extremely important to have a long-term view of the measures we are undertaking to combat the virus to ensure that they are not optimized by governments and corporations for personal gain. There is no denying mass surveillance is a risk to privacy, and will the governments give the power back?

The UK government has already admitted that it did not conduct proper privacy checks on the system, and it is no secret that the ecosystems of Apple and Google are fundamental to the track and trace app. Whilst they have allegedly ‘favoured a method that puts people’s privacy at the forefront of the system,’ it still demonstrates how we have become ‘almost completely dependent on big platforms’ In her work, The platform Society, Jose Van Dijk acknowledges that:

In a sense they are tremendous ‘facilitators’ in our daily lives, they help connect us. On the other hand, they are getting control of our daily activity by means of data flows. We have a trade off in that we give away our data in exchange for free services.’

While these partnerships might offer the necessary solutions to deal with health crises, by turning to companies with deeply worrying human rights records, we are introducing mediators that are very hard to control. We also know, from instances like the Cambridge Analytica scandal, that these companies have a ‘very definite impact on local and national democratic processes.’ Van Dijk argues that you ‘cannot fix the problems of a society if you outsource the solutions to the big coorperations.’=

So, what next?

From effectively communicating about lockdowns, to testing efficiently, ministers seriously need to clarify things more carefully in their next Cobra meeting. Longer term, the coronavirus pandemic, and the wider governmental and societal response, have brought health inequalities into sharp focus, and this must also be tackled.

In the same way that technology cannot offer a truly inclusive and accessible track and trace app to act as a cookie cutter solution during the pandemic, technology also cannot guide the government in formulating this strategy to undo the damage done by austerity measures. Oh, the irony! A plan for the future of the UK must be guided instead by our values and the lessons learned from the human consequences of this pandemic.

By Nicola Banks