I recently watched a Buzzfeed video about a woman in Texas, USA, who ‘accidentally became a meme.’ Known as ‘Kombucha Girl’, Brittany Broski recorded herself tasting Kombucha for the first time. Her face seems to physically recoil at the taste. But as she considers it for a moment, her expression changes multiple times, rapidly. In the Buzzfeed video, we see her describe how her reaction shots (‘not the video, the reaction pictures’) went viral after being adopted by ‘Gay Twitter,’ and subsequently went viral.

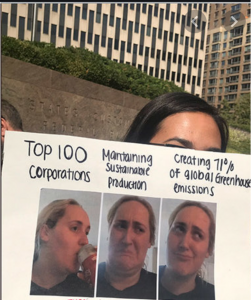

Broski also mentioned that meme had found its way onto protest posters in Hong Kong, and climate change posters in New Zealand – This is when I really started to pay attention. It really got me thinking about the value of the meme, the potential memes play as research tools, and what exactly is the function of a meme in modern society?

The meme is an outcome of participatory and online media culture, which is central to thinking about the sensibility of contemporary visual culture, and offers a very different understanding from previous academic understandings of visual culture. Where previous schools of thought focused on the symbolic meaning, representation and careful interpretation of texts, in other words visual messages can be seen as meaning-making devices, and the methodology that follows from that is that we work with images to interpret them, the meme represents a new theorization of visual culture as convergent – performed by people ‘just doing stuff’.

What do you mean, new understanding?

Let’s consider the meme in relation to the work of Gunther Kress. For Kress, the distinctive thing about contemporary text production, particularly using new media, is there is a fundamental re-shaping of how people are dealing with texts. Visual and otherwise. There are now widespread new principles of text making composition that depend in large part on re-using existing materials, while paying very little attention to the integrity of those materials. What this means is that new texts are designed using whatever is to hand in order to communicate something in a particular social context.

In a world marked by instability and provisionality, every event of communication is in principle unpredictable in its form, structure and in its ‘unfolding;. The absence of secure frames requires of each participant in an interaction that they assess, on each occasion, the social environment, the social relations which obtain within it, and the resources available for shaping the communicational encounter’ Kress, 2010, p26

See below for example. The text has been rearranged using what looks like print-outs of the meme, a white background and hand written facts about climate change.

What it might also be important to consider is the work of Henry Jenkins, who emphasizes how in many fields of contemporary practice, what matters is that it is no longer large institutions which are the significant producers of social knowledge. Groups can now produce and disseminate their social realities as has never been seen before. With online technologies, more and more people can engage. He calls it ‘convergence culture’.

The emergence of content which flows across numerous media channels, and also towards multiple ways of accessing content, combined with ever more complicated relations between top down media and bottom up participatory media marks a paradigm shift! We have seen that visual culture is no longer located in images that require reading, rather it is enacted across a highly complex social field where it serves to show and to enact that field and its distinctions.

Ok, but what does this have to do with what memes tell us about society?

Well, there is a clear parallel between what is described in the work of Jenkins and Kress, and what Gillian Rose calls visual research methods. In convergent visual culture, images are used in very diverse ways, they are created, shared, cropped, mashed, and otherwise circulated. They work to record things, to represent things, to argue, and create effect. They are meaningless, can be cute, or silly, and also extremely important to the people who have created them. They can be sent as messages to maintain or destroy social relationships. They achieve through what they show, how they are seen, and also what is done with them. What matters is what is done with them. This can certainly be said for the Kombucha Tea Girl meme.

But if what Rose is saying is correct, that the way visual researchers use texts can also help us understand a much wider cultural shift that’s taking place. We’ve seen significant changes in how we create and use images, and using visual research methods as an approach to creating social science knowledge has become massively popular in a short space of time – which is no coincidence.

With this in mind, the production of the meme, with all the key features that characterize new media artefacts, such as participation, self-organization, amateur culture, networks, etc epitomize the way visual research methods treat images. This practice is a reflection of contemporary visual culture, and also an important contribution to our understanding of it, demonstrating the power of the meme as a tool for cultural research.

Broski herself mentions that the value of memes comes because they ‘don’t need language,’ and thus they can be relevant and understood in any language. The value of the Kombucha tea girl meme in the protests is that it can communicate effectively to other protestors, and to the wider public to hopefully encourage them to join, but it also is valuable in communicating about the culture within the protests themselves. I’d say that was pretty memeingful!

Rose, G. (2016) Visual Methodologies, 5th edition. London

Jenkins, H. (2008) Convergence culture: where old and new media collide. updated edition. New York: New York University Press.

Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

NCRMUK, Gillian Rose, Key lecture: Now you see it now you don’t, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7Z7AR2RZ4Y