What a time to be alive, isn’t it? As learned from Hylland Eriksen: “Everything globalizes except democracy” (Eriksen, 2014: 86). Even a virus – we must now add.

But let’s talk about the internet.

Internet

The Internet has passed through us like a gale, like a hurricane. All of a sudden and without prior notice, it has been established in our daily lives. Remarkably, as we people are so adaptable, it is difficult to measure what the mediatization of our lives and our relationships has really meant.

Like it or not, the internet is a speeding train impossible to stop. We don’t even know the route. We don’t know where it is taking us. And the rails on which it travels are completely unknown. It travels through the air, water, space, interdimensional… The least it does is touch the ground.

In the specific field of activism and in the (not at all specific) area of communication for social change and information and communication technologies, the internet has opened an entirely new dimension. The mediatization and the greater democratization (in no way complete or fair) of the access to information and to be listened to, have transformed activism worldwide. I am not referring only to the use of devices, but to all that this entails: the ability of the internet to make visible, to recognize own spaces, to promote discourses, to question them. With all its drawbacks, of course.

Acceleration

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the speed with which everything changes. This is wonderfully well explained by Hylland Eriksen: “Acceleration is a central feature of globalization and indeed of modernity. Everything, it seems, happens faster and faster, bringing disparate parts of the world closer to each other, leading to frictions of the kind that we may call overheating effects ”(Eriksen, 2014: 41).

And in all this madness, the contents are so many that it’s overwhelming. There’s loads of frivolity (no doubt), of terror (100%) and fake news, and the boosting of hate and discrimination speeches… We know that. And specifically, in the field of social and environmental justice, we have our huge share of frivolity: clicktivism, white privilege, white gaze, greenwashing, whitewashing, (we kill it at naming), etc.

But the reality is that never before in the history of mankind (not even in the most intellectual groups of white men smoking cigars and drinking brandy) has the number of ideas, theories and relevant and extremely complex questions shared in a group come close to my Instagram’s feed. (Or any other activist or academic minimally active in social networks’ one).

This on the one hand is great, but on the other hand profoundly puzzling. Especially since the speed with which we go from one topic to another is insatiable. And this frenetic acceleration makes a topic that is not current (disproportionately current, like immediate) worthless. The social trend leads us to replace it with another at full speed. And we get tired increasingly fast because we psychosocially get used to this speed that engulfs us (due to brain neuroplasticity – look it up, it is worth it).

Activism – victimization, frivolity, relevance, and joy

But of course, in activism, this is especially striking because we are not talking about the pants that are in fashion and will stop being so in a month (although the consequences of fast fashion are also insane). We speak of social and environmental injustice! And this acceleration of discourse uniquely affects visibility, relevance, and therefore the listening of collectives and individuals.

This is why I have been reflecting about frivolity, relevance, and joy. Some questions that come to mind are: Why do we tend to assume that a pedagogical content is more transformative than one that, at a certain moment, can be considered frivolous? How is that judged? How do you judge it from privilege (in my case as a white woman)?

One of the (many) vision problems derived from the defense (conscious or unconscious) of the privilege that (we) white allies have is that we tend to victimize others. As in a sophisticated dimension of Boltanski’s “politics of pity” (1999) we legitimately denounce (in my opinion) an injustice but unconsciously tend to picture the people whom it affects most as defenseless victims.

What’s in an ally?

Personally, I am very critical of a discourse within activism that basically maintains that as an ally you should stay on the sidelines and only exercise active listening and share content. I think it is one thing not to take over spaces and quite another to do nothing more than share content on social networks from time to time for “other’s” struggles. I believe very important the understanding that if we promote this, we are ultimately reserving privileged spaces and training to fight only against oppressions that affect us personally. Does that sound right?

I believe that as allies we must contribute to dismantling the power structures, contributing with, whatever it is, that we do best. Of course, always bearing in mind that our role is to enhance the spaces, claims, complaints, and experiences of the people who suffer most the axes of discrimination in question, not ever overshadowing other people’s spaces. And always also from active listening, participation, and avoiding being short-sightedness. I also believe that being mistaken is alright, that feeling uncomfortable is part of questioning own privileges and that humility and questions are the best way to be useful.

That is one of the reasons why human diversity, indigenous knowledge, and the decentralization of the white gaze are one of the most valuable things humanity can count on because otherwise challenging cultural hegemony and social and power biases would be almost impossible.

People’s multidimensional experiences

And in this questioning, I return to the reflection on victimizing. Victimization is another example of how white people reproduce colonialist dynamics of domination. When we victimize, we are sharing a simplistic and deeply fragile representation of people traversed by social injustice.

When someone is seen only as a victim, her lack of space and social weight is being perpetuated. This is in no way transformative. Nor is it a valid deconstruction of privilege because as an “ally” you are also perpetuating your power and your space as a, for instance, white activist.

Unfortunately, I believe this is partly extensible to the communication of some discriminated groups (including those that do concern me as a “victim” rather than an ally). And here is where joy comes in.

I wonder if one way to guarantee that the visibility of oppressed groups is more solid and more capable of withstanding this changing reality and the onslaughts of systemic violence is precisely joy.

Joy

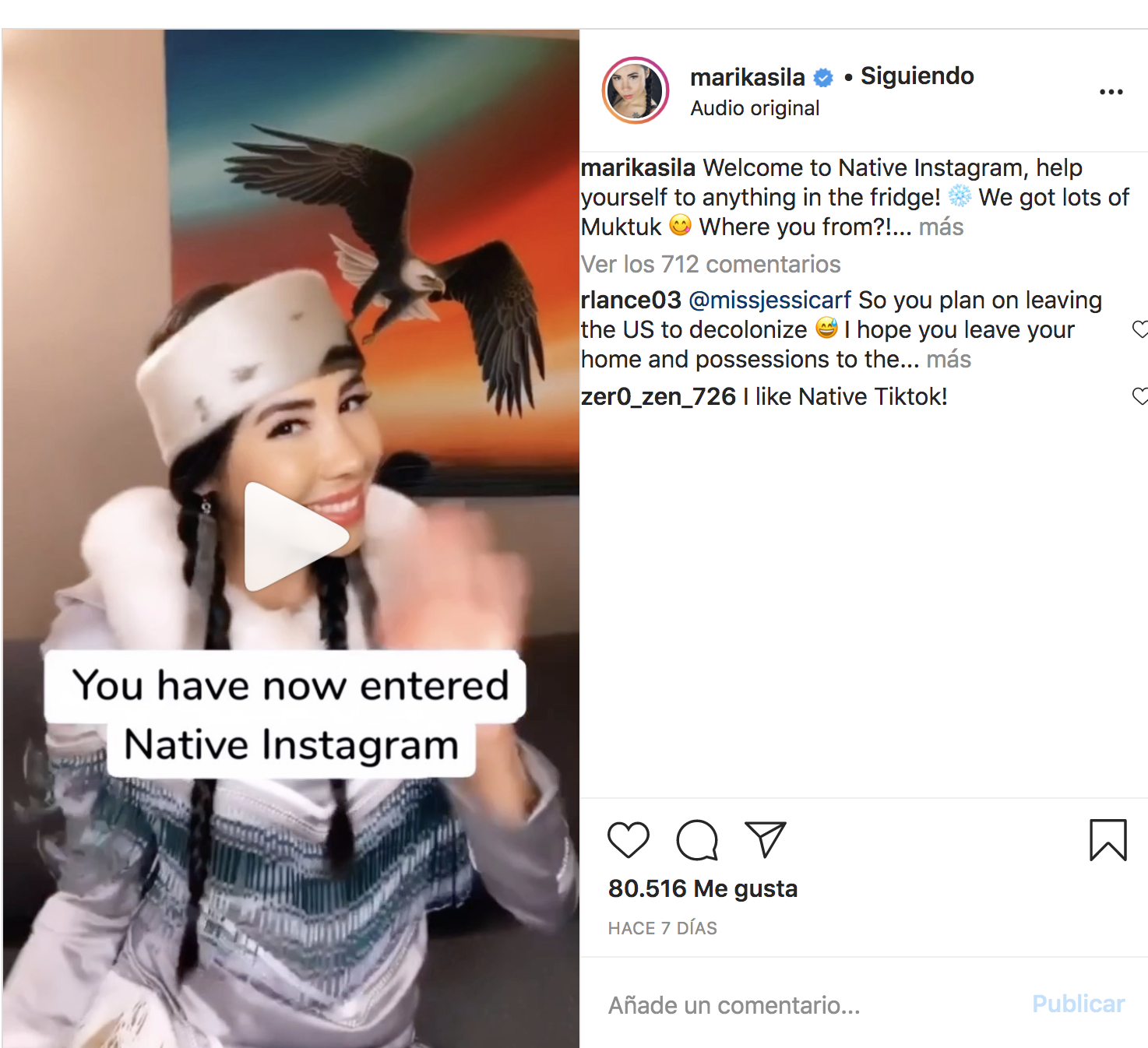

Tens of thousands of BIPOC activists, queer people, trans, non-binary, non-cis, feminists, disabled people, sick people, the elderly, etc. are also vindicating themselves from joy through Instagram and TikTok. Of course, there are tons of others (or the very same) who advocate in a more intellectual, political way. But I think the former also has value and is important to reflect on it.

Before, I watched all these videos in a somewhat critical way. I was worried that they could further dilute activism, sweeten even more the social commitment of citizens. Lately, I have been reflecting on the way in which this brings own experiences closer to the general public and allows people to make stronger foundations for the spaces they legitimately own.

Obviously, I am not saying that this should displace the more pedagogical messages. This would mean depoliticization and it has nothing to do with what I mean here. But don’t you think that these joyful messages are also interesting in terms of visibility and social weight in the world we like it or not share today?

Boltanski, L. (1999) Distant Suffering: Morality, Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eriksen, T. H. (2014). Globalization : The Key Concepts (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.