In recent decades, we have seen a significant development and popularization of the Internet, personal computers and mobile technologies. What is more, is that ICT technologies are entering new areas of life, which I briefly mentioned in my 1st blog post. Mobile devices are becoming an increasingly important tool for learning, work, entertainment, and the Internet is becoming an increasingly important source of information and knowledge, means of communication, trade, entertainment and social life. Though, not everybody has access to new technologies and not everyone can take advantage from the potential they bring. In other words, there is a gap between the underprivileged members of society who do not have access to tech devices or the internet, and the wealthy, middle-class from urban and suburban areas who have access. The threat related to the raise of the ICT society is the issue of exclusion, whether it is entire geographic region or a social group from it.

Quite a few reports highlighted the growing problem of “digital exclusion” in the past. For instance, the study conducted by Geraldine Beazley in 2012 provided evidence that government efforts to move services online were particularly disadvantaging low-income groups, including older people and those with disabilities. Now, 8 years later, the researchers still believe there is a very high likelihood of this trend continuing. Let’s look into “digital divide” and what it actually means (Beazley, 2012).

The expression became popular among concerned parties, such as researchers, intellectuals, scholars and policy makers in the late 1990s and was first introduced by Lloyd Morrisett, the former president of the Markle Foundation, who referred to it as a “digital divide” between the information “haves” and “have-nots.” At that time the obstacles were mostly related to the cost and knowledge (Hoffman & Novak, 1999). Traditionally contemplated “digital divide” was considered as the gap that exists between individuals who have access to internet and those who lack it. With growing penetration rate of the internet and ICT usage as a whole it is now becoming a corresponding inequality between those who have more and less bandwidth as well as more or fewer skills.

Why do we believe so greatly in the power of ICT when for the preponderant part of society access to the ICTs is not a reality? Many communities throughout the world lack adequate technological knowledge and equipment both in Global South and North.

In the past discourses related to the cyberspace and its relationship to social exclusion and inequalities, there were two contrasting standpoints (DiMaggio et al 2001, Castells 2001). From one side it was expected that the Internet would become an opportunity for people with the lowest levels of income to improve the living situation and social promotion. This optimistic notion presented the Internet as a tool to reduce social inequalities, which was supposed to happen through the decrease of the cost of information, hence enabling people with low incomes to progress, benefit from the knowledge, and acquire new skills. The supporters believed that technology will improve the standard of living in developing countries and unprecedented changes will take place in the functioning of the global economy due to the high potential of new technologies that could create higher standards of living for all people. It was highlighted that the Internet creates a unique chance to access information and knowledge in a simple and cheap way, and that will make an impact on the ability to access education and participate in more equitable job contest. This optimistic perspective was seen amongst others by Anderson and Bikson, who believed that the Internet would lead to a situation in which everyone has the same chance of succeeding by leveling the playing field (Anderson et al, 1995).

Nowadays, there are still many enthusiasts which are optimistic about the next 50 years of the digital life, for instance:

Andrew Tutt, a law specialist and author of “An FDA for Algorithms” :

We are still only about to enter the era of complex automation. It will revolutionize the world and lead to groundbreaking changes – in almost all aspects of modern life.

Arthur Bushkin, an IT pioneer from Verizon:

Of course, the impact of the internet has been dramatic and largely positive. The devil is in the details and the distribution of the benefits.

Mícheál Ó Foghlú, from Google:

“Despite the negatives I firmly believe that the main benefits have been positive, allowing economies and people to move up the value chain, ideally to more rewarding levels of endeavor.” (Anderson J. et al, 2019)

On the other side, disbelievers riposted that the Internet will primarily benefit people with high socio-economic status, who will be able to use the resources you already have to take advantage of the new one earlier and better technology. There individuals will be able to use the cyberspace earlier, will have easier access to quicker broadband, and will also be able to count on social support, enabling better and easier use of the Web. The pessimists indicated that the inequalities would deepen over time, according to the principle that the poor will become poorer and the richer will become even richer, mostly due to easier access to the Internet, better understanding of it and therefore better us of it.

As Tim Unwin stated:

The poorest and most marginalized are also more likely to suffer disproportionally from some of the darker aspects of Internet connectivity. (Graham, 2019)

Digital and social exclusion

In 2016, a research was commissioned by Carnegie UK Trust with the support of Scottish Government, to analyze the relationship between digital exclusion – lacking access to online environment – and social exclusion. The researchers investigated available literature to identify present-day state of theoretical understanding of the subject, and links between 2 types of exclusion. In the 1st phase of the study they distinguished 7 different indicators of social exclusion including the following:

- Convenience of local services

- Active living

- Transport

- Socially Connected

- Mental Health

- Use of local services

- Long-term physical and mental illness or

- Disability

The second part of the study scrutinized whether cyberspace access was a significant factor in each of these components.

The literature review highlighted a number of key findings:

The digital divide is based around social inequalities that drive low levels of access and skills to use the internet.

Those who are socially excluded are less likely to use the internet and benefit from the internet applications that may help them tackle their exclusion.

Digital exclusion has the potential to exacerbate social exclusion e.g. in terms of poor educational attainment and some studies have shown a positive effect of digital participation on indicators of social exclusion (Hope et al, 2016).

Even though, the literature does not assemble a precise vision of the relationship between digital and social it does emphasize that both social exclusion and digital exclusion are long-winded and complex notions. What Hope, Martin and Zubairi bring our attention to is also the fact that the literature underline the positive impacts of internet use in the context of digital exclusion (Levitas et al, 2007). Additionally, the secondary analysis that they performed confirmed the link between positive impacts of on-line participation in the dimension of social exclusion. However, some previous research highlights that high levels of internet use can be associated with lack of physical and social activity (Moreno et al.2013).

Access to the Web and other variables

Now, of course Internet has revolutionized the way me, you and the vast majority of people around the world live, but there are still countless individuals who are unable to use the cyberspace to the extent I or others do, or in many cases not at all. The Internet has been initially, by many, advertised as beginning of true digital democracy and a place, where we can inform ourselves and enhance our lives. Is it really? Well, for significant part of the global society it is, but unfortunately, many people are still cut off from this idealistic vision. A substantial portion of the community around the world cannot benefit from the on-line space.

How many people use the Internet then?

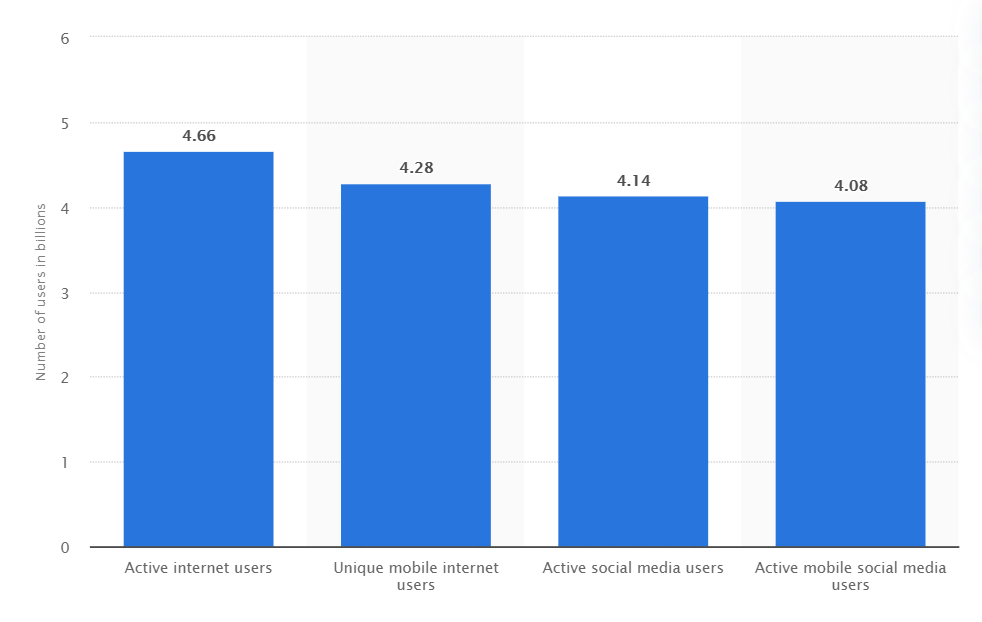

As of July 2020, almost 4.57 billion people were active internet users, encompassing 59 percent of the global population.

However, with the world’s population coming to 7, 8 billion in July 2020, as per Worldometer, have we thought of the remaining amount of 3,2 billion? The irony is, as Pepper and Jackman points out in their chapter about “data-driven approach to closing the internet inclusion gap”, that the people who could benefit the most from the access to the internet are presently lacking the connectivity. Though, the access is only one element in the journey to obtain equality, it is the foundation for fulfilling the rest. Besides the means of entry we shall think of better connections, adequate content, and ultimately look into the gender gap (Graham, 2019).

For instance, while Internet use in the capital cities of countries such as Moldova, India or the Kyrgyz Republic are at the same level as some members of Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the usage in these three states’ country sides is among the lowest on the globe. These disproportions hinder shared prosperity and constrain access to the routes out of poverty (Worldbank).

Based on available data it is quite clear that there are major differences in access to internet between developing countries and advanced economies, where it is 35 percent of the population versus 80% accordingly. It is obvious that divides concern states and regions, but it is even more concerning that there is disproportionate impact on specific communities in rural areas, the poor or particular identities, including gender, race or class (Worldbank).

In the male-dominated cyberspace, the technology and its content is developed by men and primarily focused towards same-gender audience. This was broadly discussed by Amy O’Donnell and Caroline Sweetman in their article “Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs”. While they describe internet as a place that offers routes to self-expression, their center of attention is on deconstructing the web to its roots and looking into the creators origin. For instance, they mention about a campaign Whose Knowledge? that aims to shift the focus beyond the digital divide and access and towards the biased knowledge base created by elites, which is available on the net. The campaign strives for transforming the on-line space and its content to become “less white, male, straight, and global North in origin”, and by that they aspire to decolonize the Web. The authors raise an important question of “whose tools and whose knowledge” do we find on-line and how it affects inequalities. They also fear of growing gender-based violence (GBV), since ICTs tend to provide more opportunities for abuse, whether it is trolling on social-media, sexual harassment or other. Digital spaces continue to be environments of empowerment, but also exploitation and there is certainly a need to look at it also from the gender lens.

The authors of 3rd chapter in “Digital Economies at Global Margins” investigate the effect of ICT4D in small scale farming in Africa on the case of Tanzania and Kenya. The initial thought is focused on positive impact of ICTs in the developing rural regions, where it was noticed that access to and knowledge has a greater impact on overcoming many barriers related to social and economic interactions. Humpfrey (2002) on the other hand argues that ICTs may be the cause of negative impact and widening the digital inequalities that disadvantage farmers with lesser capabilities and knowledge. To similar conclusion came Krone and Dannenberg, who confirmed the association between ICTs and sustaining asymmetric power relations, especially to control the farmers by more powerful actors in the chain.

Despite the fact that the users of personal computers and other mobile devices, individuals possessing the access the Internet continue to grow on a yearly basis, the digital divide also continues to soar at a disturbing pace. Even in the USA, from one side, part of society already connected, the richer and more educated White and Asian Pacific Islander households are adopting newer technologies faster and are connecting even more. On the other side, societies with traditionally lower penetration of the Internet and lower computer usage continue to fall far behind. According to a study conducted by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), entitled Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide, the split is broadening along already haggard economic and ethnic boarders (NTIA, 1999).

New reality of Covid-19 and mending the Breach

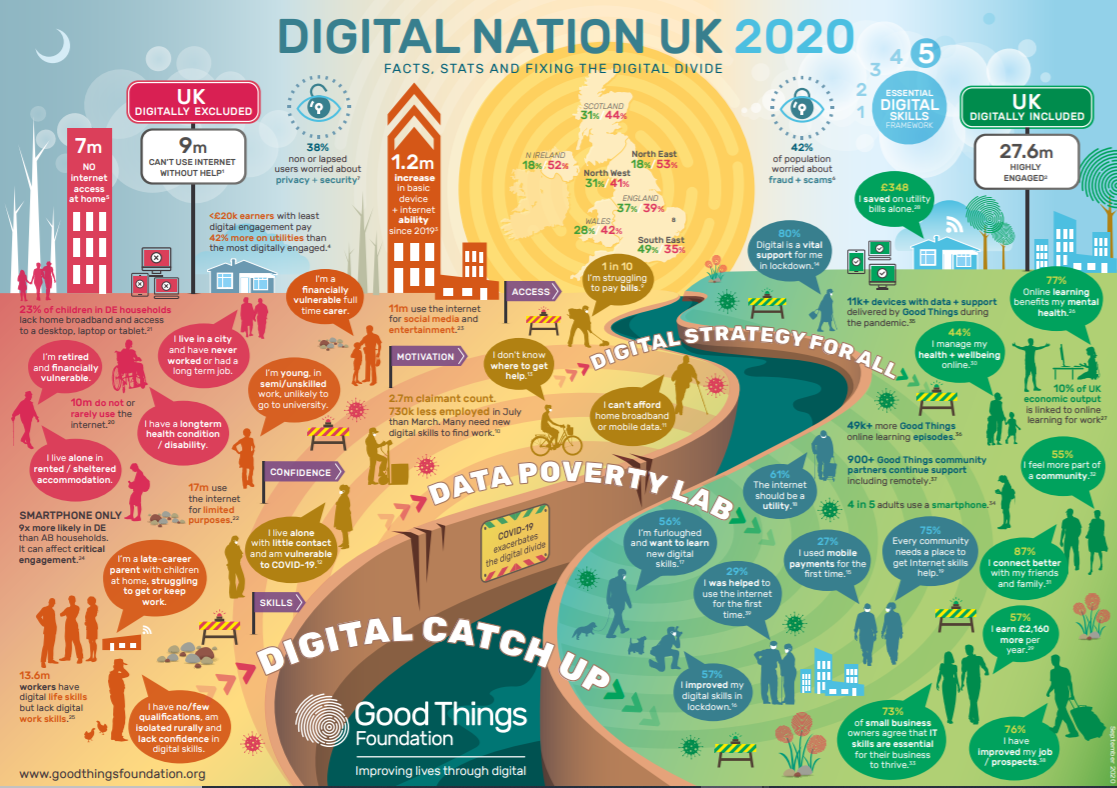

Despite the transformative impact of ICTs on society many people remain digitally excluded and the COVID-19 pandemic shines light on existing inequities. Since the outbreak of this year’s pandemic the scale of digital exclusion has been avowed and aggravated beyond previous understanding. While new actions have been rapidly and successfully delivered, substantially accelerating progress and ensuring thousands of individuals now have appropriate connectivity, there is still much more to be done to ensure no one is neglected in the context of digital exclusion. In the UK for instance, a country leading the world as a digital nation, it has been identified that staggering amount of 9 million people struggle to use the internet. One of the stakeholders within the state that aspires to improve lives through digital and tackle the most pressing social issues of our times is Good Things Foundation. Every year, the foundation publishes the updated Digital Nation infographic showing who’s digitally excluded in the UK and the reasons why they are not online. This could become an interesting example to explore to see how we could help people in digital context of pandemic.

Great Britain is also known for its initiatives towards tackling the digital issues. One of them has been recently launched by Andrew Carnegie House in response to the new Covid-19 situation. The members of Carnegie UK Trust have created a guide: “Learning from Lockdown: 12 Steps to Eliminate Digital Exclusion” towards policy makers, researchers and industry representatives to help in battling the crisis. Knowing that digital divide existed since a while, they demonstrated why tackling it is so urgent and proposed specific actions.

This year, even in my own home country, in Poland, thousands of children have suddenly disappeared from the school radars because they have no access to internet or computers. Seniors who are overwhelmed by sending an e-mail, disappeared for official institutions. Today, the Internet is no longer a question of access. Without a network, people become digitally invisible. Separation with family became dramatic, when it concerns an elderly, who do not use ICT to the extent of simply communicating with family. The latest research from Eurostat shows that in Poland as much as 53 percent of people between 65 and 74 years of age have never had contact with the Internet last year. That means, that during firm restrictions implemented by the government including for instance cashless payment system at shops, the elderly people find themselves in really uncomfortable situations. Now they have realized that without efficient navigation on the web they will not be able to live independently. At the beginning of the pandemic, they felt as if the world was slamming before their eyes. Also the new e-school in Poland caused many tears for the young ones and their parents, especially when the speed of the broadband appeared not to be sufficient for participation in the class. Not only 81% of schools pointed out difficulties in providing lessons to pupils during Covid-19, but also as much as 25% of all pupils are excluded due to the lack of device that could be used for learning, which is around 1mln Polish children. According to the Cisco Annual Internet Report, Internet users accounted for 58 percent of the total population in Poland. Meanwhile, you don’t have to search far anyway, as just beyond our Eastern border in Ukraine, the pandemic and related restrictions have deprived 60 percent of children living around the front line from educational opportunities (Sienko, 2020).

Nevertheless, the digital divide does not have to be about not having access to the internet. There could be also obstacles in using the network resulting from disabilities, both permanent and temporary, such as breaking a hand. Disability digital divide is still however a complex field that needs deeper investigation and possibly more attention from the scholars in order to make particular conclusions. It seems there is little research done up to date on this subject, end even there were many attempts, it often ends in conclusion that a further research is needed to expand the understanding of the diversity and complexity inherent in the disability digital divide as well as what is the reason of inclusion or exclusion.

There could be variety of strategies on bridging the digital divide. The United Nations includes this issue in its Sustainable Development Goal 9 (SDG9), and therefore in many places around the world we can notice emerging practices for tackling this problem. Some of them include digital literacy initiatives, Alliance for affordable Internet (A4AI), Free Basics program that offers access to basic online services without data charges (promoted amongst others by Facebook), or Starlink project by Elon Musk. How will they impact the digital inequalities, only the future will show…

Conclusion

Given the above, I maintain that digital divide will continue to be an explicit feature of the Internet in the future. The inequalities related to the digitalization and internet use will not only endure, but they will intensify over time. The key to overcome these differences is to spread broadband and learn how to use it, which will become increasingly important in the years ahead. The consequence of failing to do so will strengthen the digital divide, within which the access would be only a part of the story. Presently visible inequalities homogenize with an increasingly dense, commercialized online social matrix, developing texture of content, variety of apps as well as computing and informatics structure, that privileges particular human beings or societies over others. While some initiatives are already recognized as good examples to follow in order to bring more equality in digital environment, and bring some hope, still within this dense on-line framework there is high likeliness to endanger people to become lost in the elevating tide of digital data, which could be classified as modern day fear.

How about you? Please share your opinion.

#FixtheDigitalDivide

References:

Anderson et al, 1995. Universal Access to E-Mail: Feasibility and Societal Implications. RAND Corporation

Anderson J., Rainie L. Stansberry K., 2019. The internet will continue to make life better.

Castells M., 2001. The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business, and Society. Oxford University Press.

Digital Nation UK, 2020. Good Things Foundation.

Global digital population as of July 2020 (in billions). Source: Statista 2020.

Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., Lloyd, E. and Patsios, D., 2007. The multidimensional analysis of social exclusion. Project Report: University of Bristol

O’Donnell, A. & Sweetman, C. 2018: Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs , Gender & Development, 26:2, 217-229.

The World Bank. Brief. Connecting for Inclusion: Broadband Access for All.