ICT and development intersect in many ways and do so increasingly as both technology and development work evolve. This series of articles sheds a light on one aspect of “Development in the digital world”1, or development in a digitalized context: (mis)representations of development and the role of social media platforms and platform mechanisms in them. Are social media logics pushing to harmful practices? Are social media users benefiting from poverty porn? Can social media be used to counter these practices? The series of article reflects on these questions through four different case studies.

In the previous articles, we have explored three different perspectives on the role of social media in (mis)representations of development: the risks of celebrity philanthropy, the white savior complex on Tinder, and sometimes problematic marketing of social enterprises. These new forms of manifestation of deeply rooted perceptions of development on social media are also being countered in a variety of ways. One concept that has risen in recent years but gained especially popularity in 2020 is “cancel culture”.

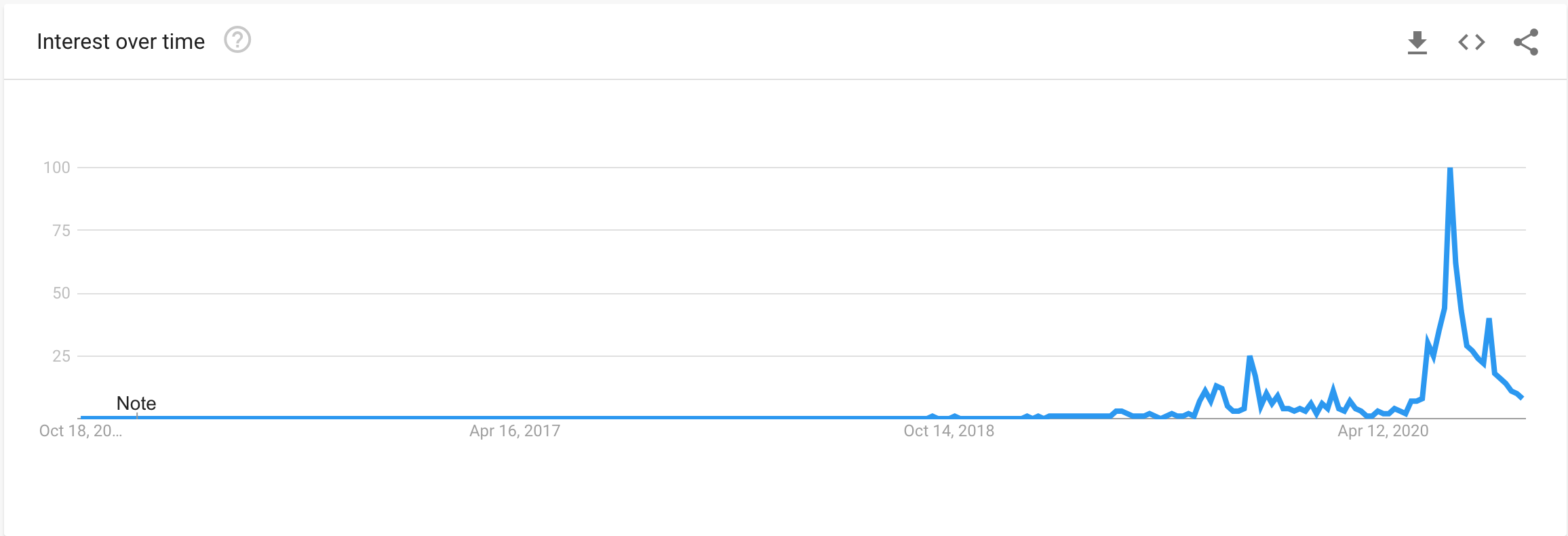

As defined by dr Tina Sikka in an interview for Huffington Post, cancel culture is “an act of public shaming that’s based on either something that is perceived or substantiated as social transgression of some kind, that hasn’t been adequately addressed through traditional channels”. While canceling is not a new phenomenon, it has taken a new extent through social media. Canceling started as a colloquial term on black Twitter to denounce celebrities’ actions, but the term has become a part of larger societal discussions in the last two or three years. Recently, the concept has been brought up increasingly also on mainstream media and among a variety of decision-makers, which is also reflected in the skyrocketing number of searches for “cancel culture” on Google in 2020 (Figure 1). Sikka describes cancel culture as being born from the need for an outlet for social issues and injustices that institutions can’t (or don’t) keep up with. It is a form of online collective action aiming to “cancel” an individual’s space on social media when they are considered to have done wrong. However, while canceling is directed at individuals, it is the form of action taken by something more relevant to society as a whole, a way to raise attention on issues that are not addressed by policy-makers through the group-pressure of a large number of people. Cancel culture rises from marginalization, and social media has provided a space where marginalized voices have a possibility to connect and amplify one another to act together.

While cancel culture is a display of the potential of social media to give voices to those who previously haven’t been given room to use theirs, the practice comes with a price. Canceling has become highly discussed in 2020 and made headlines in many notable news media because it has been brought up increasingly by those finding themselves targeted by canceling. For instance, in July 2020, Donald Trump denounced cancel culture and went as far as comparing it to totalitarianism and JK Rowling, Noam Chomsky, and around 150 writers, academics and activists signed an open letter denouncing, without explicitly mentioning the term, the threat posed by cancel culture to democracy. The critiques, who often consider themselves victims of such practices, are afraid of the consequences canceling can have on their lives and careers, fear the suppression of diverging or unpopular opinions, or false accusations. These concerns are a risk of canceling. Nevertheless, if going back to the power dynamics behind cancel culture as a movement coming from those in an underprivileged position in relation to an issue, aimed as individuals in power positions, it can be asked whether the acts of oppressed individuals and groups can be judged to be oppressive towards their oppressors. I argue that if an issue has come to be so unbearable that a wide group of people decides to come together and target only one individual, it is so deeply rooted that such an act, aimed as a wake-up call to the rest of us, is not enough to switch around such a power dynamic. Indeed, cancel culture in the end rarely has major repercussions for those targeted, and the fact that the concept of cancel culture has become widely known only in recent months in the light of mediatization of acts of celebrities or other people in high positions of power being targeted rather than through the rise of marginalized voices on topics dismissed by policy-makers, displays the remaining asymmetry of power.

Calling out individuals doesn’t, therefore, seem to be efficient to achieve its claimed goal, and leads to a lot of negative speech online. Is cancel culture then of any use and is the power asymmetry enough to make it justified? Targeting simply individuals is not by itself a way to change a system, but rather a wake-up call. It should also be taken into consideration, especially in the context of social media where slacktivism is only one click away, that participation in denouncing an individual’s actions should always be done mindfully and with consideration… which is often not the case and can lead to decontextualization of issues and distortion of facts. It is important to take the time to understand the context of the phenomenon at hand, the different perspectives and actors at play, and the possible repercussions of such practices to ensure to not turn cancel culture into a weapon against those it gives a voice to, but also to not construct an overly simplified perception of reality that, instead of resulting in social change, merely destroys the career of one individual.

As a new phenomenon, the body of research on cancel culture remains very limited, but recent findings have displayed some of the limitations of such social justice campaigns as the use of social media often leads to a number of issues ranging from a simplification of issues to individualization of systemic issues2. At the same time, cancel culture is a symptom of way greater issues, and it is important to go beyond the practice itself to induce social change and change instead of directly labeling it as a toxic practice and dismissing what it truly exists for3.

While more research needs to be done on the topic, these first findings support the complexity of cancel culture as a practice and point out that it may lead to harmful results for different actors involved. I therefore what to emphasize one more time the importance for each of us to use a critical mindset when encountering social media movements to make sure that what we engage in can lead to positive social change – and previous examples have also shown that online social justice movements can do this too.

1 Roberts, T. (2019). Digital Development: what’s in a name? Appropriating Technology, August 9.

2 Bouvier, G. (2020). Racist call-outs and cancel culture on Twitter: The limitations of the platform’s ability to define issues of social justice. Discourse, Context & Media, 38.

3 Ng, E. (2020). No grand pronouncements here..: reflections on cancel culture and digital media participation. Television and New Media, 21(6), 621–627.