“As I cast to sea my web, in the hope of catching fish in my net, I cast words across the web, catching people’s thoughts through the inter-net. Raising awareness about Indigenous issues by using social media. We Shall Idle No More, Or Listen to lies spread by pop culture idols no more […].

Te Kahu Rolleston from the Tauranga people (Rolleston, 2015)

Reach or social transformation?

The way that most of us have been raised and socialized leads us to have a fascination for success stories, big stories, those with which we empathize without any resistance, and that connect us worldwide to millions of other people. When talking about social movements and activism on social networks, the examples that generally come to mind are those which arouse the most mainstream attention: #OccupyWallStreet, #FridaysForFuture, #Indignados, etc.

This makes sense, of course. And they are absolutely necessary mobilizations. But in terms of communication for development and social change, I wonder if giving so much attention to reach for the sake of reach makes sense. Wouldn’t it be more logical to weigh the transformative capacity of citizen mobilization? Shouldn’t we promote what Judith Butler calls materialization: how voices transcend power hierarchies or not to contribute to collective worldviews and, consequently, make social change possible (Couldry, 2010)?

In the aforementioned social movements, the individuals and groups that pushed them already had social weight, they already had space and recognition in the public sphere and in the digital space before gaining momentum as a social movement. That is one of the reasons why they became so internationally and transnationally popular: part of the work was already done.

“Poverty of voice”

Many other individuals, groups, and communities, though, face “poverty of voice” (Lister, 2004; in Tacchi, 2015). The axes of discrimination that intersect them, the hierarchies of power, and the systemic violence, make it impossible for them to achieve enough social recognition to get their voices heard. A fundamental example of a segment of humanity with a considerable lack of resources to exercise its own voices (Appardurai, 2004: 63) is indigenous peoples.

The reality of indigenous peoples around the world illustrates Kimberle Crenshaw’s intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989). Indigenous people tend to be some of the most ‘multi-burdened’ at both the local level – in the countries where their ancestral territories are located – and geopolitically. They are intersected by multiple axes of discrimination and are often conceived as the most distant others by the culturally hegemonic.

The orientalist representation of indigenous peoples that majority and hegemonic societies produce and reproduce dispossesses them. It first dispossesses them as “poor”, “uneducated”, “racialized”, “illiterate”, “backward”, “savage”, while maintaining their tribal way of life; even though these are projections of a way of living and understanding life and what exists (Western ontology) that has nothing to do with their own worldviews. And once engulfed, forced to cultural assimilation, to adapt to the margins of globalized capitalist Western societies, it dispossesses them by judging and putting shame on them for the “decadence” they have been forced to.

Indigenous peoples have never had enough social weight in recent history to ensure that their demands – and, in many cases, their cries for survival – can break through the walls that silence them.

Is the latter changing with information and communication technologies? Does social media provide an opportunity for indigenous peoples to weaken the systems of oppression that silence them and deny them access to social recognition?

The answer is a resounding yes. There are dozens of digital activism campaigns and social movements carried out by indigenous groups that are providing them with unprecedented visibility and capacity to denounce abuses and atrocities. In this post, we want to share three examples – but we would be thrilled to read some more in the comments.

#ForaGarimpoForaCovid, (#MinersOutCovidOut)

“Praharayu warë wamaki! Yanomae Urihiha Xawara wa praharayu!

We, the Yanomami, do not want to die. Help us expel more than 20,000 miners who are spreading Covid-19 throughout our lands. ”

The Yanomami people is the most populous relatively isolated people in all of South America. Their lands stretch some 17.8 million hectares between the jungles and mountains of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela.

In June 2020, after the threat of covid19 looming over several Yanomami communities, various associations of the indigenous people came together to promote this digital action. Its goal is to obtain signatures and send emails to gain pressure on Brazil’s government. Its ultimate purpose, to expel the more than 20,000 garimpeiros (gold miners) who are invading their territory and who pose a constant threat of genocide through the contagion of covid19 as well as other diseases against which the Yanomami have no immunity.

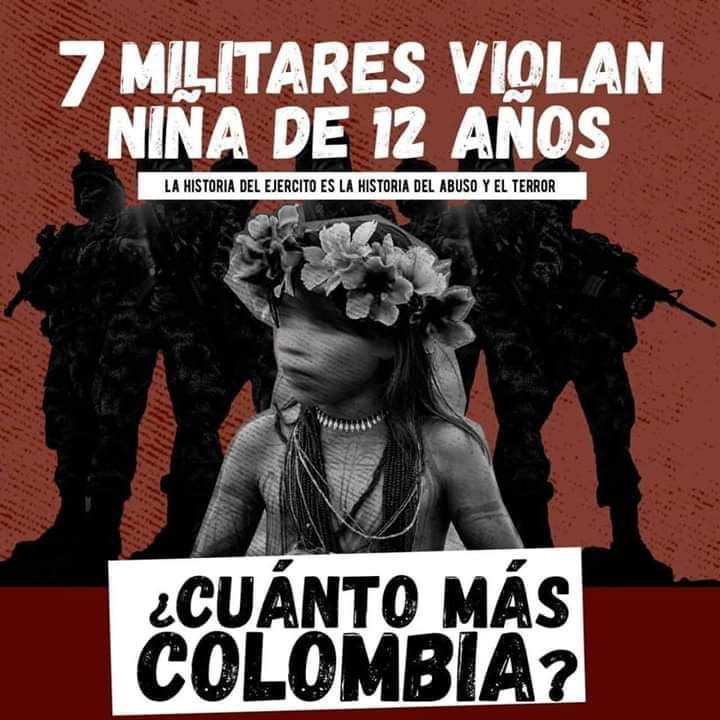

# JusticiaParaLaNiñaEmbera (Justice for the Embera girl)

As the journalist Beatriz Valdés Correa explained in the open interview that Survival International activist Fiore Longo conducted on Instagram last Friday, if indigenous peoples are one of the most dispossessed and vulnerable groups, indigenous women are the target of even more structural and symbolic violence.

Sexual violence against indigenous women by non-indigenous men is systematic and systemic in a good part of the world. It is so normalized that in many places raping an indigenous woman has its own designation. For example, as Beatriz Valdés explains in the interview, in Colombia the word “Makusiar” is used to describe the act of raping an indigenous woman from the Nukak Maku people.

One day last June, an 11-year-old Embera Chamí girl who was picking guavas was kidnapped and raped by seven soldiers between 19 and 22 years old. The news shocked public opinion. The hashtag #JusticiaParaLaNiñaEmbera began to be used to denounce the normalization of sexual violence against indigenous women and girls in Colombia. Little by little this is motivating more indigenous women and girls to find the strength to report sexual abuses. It has also made media and society pay more attention to this systematic violence.

It is by no means an isolated case nor an exclusive reality of Colombia: #JusticiaParaJuana (Argentina), #MarashtraRape (India), #OrangeShirtDay (For the crimes in residential schools including sexual abuse) are some more horrific examples among many others.

#IndigenousDads

During the summer of 2016, the Australian program Four Corners broadcasted images of brutality and abuse of six indigenous boys at the Don Dale detention center in Darwin. They were tear-gassed, kept in isolation, and systematically beaten. The images showed 13-year-old Dyllan Voller being harassed, stripped, and beaten by the guards. He was forced to remain hooded and tied to a chair for hours. The center alleged they had to do so because there was risk of suicide.

Following these events, on the day of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children’s Day, The Australian newspaper published an incredibly racist comic strip by illustrator Bill Leak. In the image, the blame was put on victims and families. Aboriginals were stereotyped in a profound harmful way: a guard appears holding an indigenous child by the collar of the shirt while saying to the father: “You’ll have to sit down and talk to your son about personal responsibility”, to which the father, holding a beer can, replies: “Yeah right what’s his name again?”.

Despite thousands of complaints, the hate crime prosecutions did not prosper.

However, Australian and Torres Strait Islander’s indigenous peoples turned this into a social tide to demonstrate the contrary. Through the use of the #IndigenousDads hashtag, indigenous women and men began sharing photos of their proud fathers, grandfathers and children to challenge the stereotype and inspire change.

“I was going to quit, but then I remembered who was watching” ✊🏿✊🏿✊🏿#WarriorUP!!#indigenousdads @ZachsCeremony pic.twitter.com/HzJrP5eFdS

— Alec Doomadgee (@alecdoomadgee) August 6, 2016

No only do I know my sons name but I named a superhero after him. #IndigenousDads #Cleverman pic.twitter.com/mfvd0vyc4S

— Ryan Griffen (@RyanJGriffen) August 6, 2016

My Dad was a hard working, loving, protective, supportive, generous man #IndigenousDads pic.twitter.com/5NdXXGmnFu

— Leeanne Enoch MP (@LeeanneEnoch) August 6, 2016

An impromptu photo shoot with my Jowundaji (Son). My role as his Garjajah (Dad) is first & foremost #indigenousdads pic.twitter.com/MhQQ7YHKLK

— Warlngundu Ellis (@warlngunduellis) August 6, 2016

I’m proud to be his father and proud to be Aboriginal. Our culture is our strength. #IndigenousDads. pic.twitter.com/TAshR17NiH

— Yaaran (Aaron Charles Ellis) (@bigibila) August 6, 2016

Skillful ICT users

All of these are great examples of how indigenous groups around the world are using the potential of information and communication networks and technologies. It also shows how despite the fact that in some tribal communities technology is simply not part of their daily reality, in many other cases and despite the undeniable digital divide, many indigenous peoples are avid ICT users. Do you think ICT4D academic research is giving enough attention to them?

Don’t forget to share some other examples of indigenous collective actions in social media with us in the comments.

References:

Appadurai, A. (2004). “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition”, in Rao, V. and M. Walton (eds.). Culture and Public Action. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press: 59-84.

Couldry, N. (2010). Why Voice Matters: Culture and Politics after Neoliberalism. London: Sage.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. u. Chi. Legal f., 139.

Lister, R. (2004). Poverty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Rolleston, Te Kahu, Social Media Exploration 1.1, Journal of Global Indigeneity, 1(2), 2015 Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/jgi/vol1/iss2/9

Said, E. W. (2003). Orientalism. UK. Penguin Classics

Tacchi, J. (2012). Open content creation: The issues of voice and the challenges of listening. New Media & Society, 14(4), 652-668

Tacchi, J. (2015) ‘Stillness, Voice, Listening: diachronic approaches to researching communication for development’ In Tufte, T. Hemer, O. and Hansen, A.H. (Eds.) Memory on Trial: Media, Citizenship and Social Justice. Berlin and London: Lit Verlag.

Wilson, Alex & Carlson, Bronwyn & Sciascia, Acushla. (2017). Reterritorialising Social Media: Indigenous People Rise Up. Australasian Journal of Information Systems. 21. 10.3127/ajis.v21i0.1591