Welcome to the third blog post in the series gender, development & ICTs. Looking through a gender and intersectional lens, I am concerned with questions of who designs ICTs and who creates the content online while highlighting some initiatives working for diversity and equality.

Who shapes the content online?

The digital revolution is changing how we live and relate to each other, but it is not affecting everyone equally and in the same way. Existing power relations in society and a person’s multiple, intersecting identities when it comes to among others gender, social class, geography, and ethnicity affect the access to and benefits from technology. ICT can be a powerful tool to enable access to knowledge and resources, collectively fight for social justice, and challenge norms and stereotypes. Though, when talking about the possibility to use technology to challenge power relations, achieve empowerment and transformative agency, it is important to look at who shapes most of the content available online.

As mentioned in a previous blog post, even though most of the people using and experiencing the internet are from the global South, they are far from the ones producing the majority of the content. Most online public knowledge is still formulated and edited by white males from the global North, even content written about the global South.

Initiatives for the inclusion of more voices

Whose Knowledge?

Anasuya Sengupta is co-founder of Whose Knowledge? and explains in an episode of the podcast “Our Voices, Our Choices” that the campaign is concerned with the power and privilege causing certain stories to be told while others remain unheard and unseen. Whose Knowledge? supports marginalised people to create content and spread their own knowledge to broaden the sources on which the world’s knowledge is based and to work to democratise and de-colonise the internet. The internet, she argues, should be challenging the prejudices of the offline world, not deepening them.

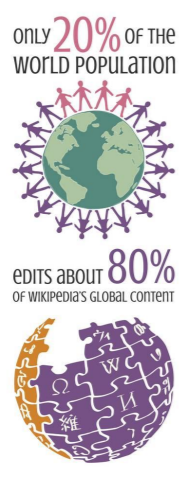

A project which has taken place every March to May since 2018 is the challenge #VisibleWikiWomen, striving to make women more visible on the world’s fifth most visited website, Wikipedia, and the broader internet. 80% of Wikipedia’s content is edited by 20% of the world, i.e. mainly white men from Europe or North America. Focus is on raising awareness and writing content especially about coloured, indigenous, and trans women in the global South who have done great deeds within anything from activism and health work to writing. During the physical events around the world (and in 2020 online), participants learned about licensing, use, and consent with Wikipedia, over 14000 images were added to Wikimedia Commons, and many articles were published about people of different gender, colour, and with diverse backgrounds.

Okvir

On a similar mission, Whose Knowledge?’s partner organisation Okvir is concerned with illuminating marginalised voices of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, and asexual (LGBTIQA) persons in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Their goal is to make authentic LGBTIQA experiences visible online, spark dialogue, and challenge prejudices.

Okvir acknowledges that much knowledge in the world is oral and that experiences of LGBTIQA persons in Bosnia and Herzegovina are mainly shared within a closed community invisible to the public. Thus, digital storytelling is used as a tool to help people process their experiences through sharing their stories in their own written words or spoken voice for example about experiences of social exclusion and LGBTIQA-phobia, accepting their sexual orientation and/or transgender identity, or the importance of support. Participants decide themselves what should be visible to the public and can stay anonymous, and they learn skills such as how to use open-source programs.

Who designs the ICTs?

The topic of content creation online is closely connected to questions of who designs the ICTs in the world, for what purpose, and for whom. It is relevant to ask who has the power to shape technology and decide what it can be used for.

The tech industry is highly affected by gender disparity as men still dominate careers in tech design and new technology. O’Donnell & Sweetman (2018) argue that the fact that content and tools are often developed by men means that ICTs are likely to be fitted to the interests and needs of men. There is a danger of underrepresentation of those who are among other gendered and racialised from the global South. When ICTs are designed by the few according to their experiences and knowledge, we miss out on learning from diverse perspectives and understanding people’s different needs for technology in varies contexts.

In many societies, technology and science are still viewed as being suitable mainly for men leading to girls and young women shying away from studying and aiming for careers within the field. Director Milagros Sáinz of Gender and ICT at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya argues that many girls and women have a technical interest, but do not develop it for example due to family constraints or social norms pushing for other “more suitable” careers for women e.g. within health and care. What is needed, she argues, is for more girls is to see and meet women already working in the field, to learn from their experiences, and imagine technology as a possible career path.

An initiative to reshape the tech industry

AkiraChix

An organisation working to balance the gender gap in tech is AkiraChix, founded in 2010 in Nairobi by a group of women. The organisation’s aim is to teach girls and young women hands-on technical skills and mentor them towards careers in technology-related fields. The initiative takes a holistic approach as focus is not only on practical training and teaching skills, but also on building the confidence of girls and young women to be future creators, driving forces, and leaders in the IT-industry.

Co-founder Linda Kamau explains that there is a big digital divide in Kenya and that the tech industry in the country is highly dominated by men. Whereas many Kenyan girls are destined for low-skilled and poorly paid jobs, AkiraChix wants to offer girls from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds a way of breaking this vicious cycle by learning a profession and becoming a part of a supportive network of women in tech. Kamau’s dream is to see a more positive environment where women are leaders and decision-makers in the tech industry.

During the signature one-year fully subsidised programme codeHive, the girls live on campus and learn skills such as coding, mobile application development, graphic design, and business planning. During the challenging times of the global pandemic, the girls live at home and many do not have access to a computer. AkiraChix is trying their best to adapt to the situation, and therefore, they are using WhatsApp to teach useful skills such as syntax and programming language.

Addressing the Gender Gap in the Tech Industry

Women and marginalised gender groups making their way into the tech business does, of course, not necessarily mean that prejudices will disappear, or equal working conditions automatically will take place. Though, providing people with practical skills, the opportunity for a career in tech, and a support network is a beginning.

Besides looking at people’s access to ICTs and ownership over devices, it is crucial to also analyse questions of who designs technology, who creates the content available online, and whose voices are heard. In other words, can all fairly contribute to and take part in the tech industry, and are ICTs fitted to their needs? To strive for inclusion and equality, there must be potential for more marginalised groups and individuals to contribute to the knowledge available online and to benefit from technology.

References

- O’Donnell, A. & Sweetman, C. (2018) Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development. Vol 26(2), 217-229.

Online sources

- AkiraChix

- Digital Freedom Fund – The First Steps to decolonialise Digital Rights (24 September 2020)

- Okvir

- Podcast: Our Voices, Our Choices – Feminist Digital Disruption during the Covid-19 Pandemic (27 August 2020)

- SIDA (2015) – Gender and ICT

- Webinar: Programa Radia – Tecnología y género (16 June 2020)

- Whose Knowledge?

- Whose Knowledge? report (2018) – Our Stories Our Knowledge