In my first post, I incorporated Amartya Sen’s approach that development must be judged by its impact on people, their choices, capabilities and freedoms, making migration (people on the move) and how we communicate about it, an ideal subject to explore ICT as a vector of development. I have already presented examples of ICT used to analyse migration data, facilitate communication during migration and enable economic integration of migrants. Whilst a few ‘grassroots’ initiatives came up in the examples I presented of social media used during/about migration, the majority of examples present in the blog series come from ‘traditional’/institutional humanitarian development actors, such as UN agencies, international NGOs and national development agencies, allowing for a broad assessment of how ICTs are used by this group of stakeholders to communicate for migration and development .

In this, my final piece, I will therefore revisit the main themes of my second, third and fourth blogs and situate them within academic discussion as I attempt to return to the question posed at the end of my first blog reviewing technology’s inclusion in global migration and development frameworks: whether ICTs deserve explicit inclusion in such frameworks, beyond their potential for data collection for border management. For this purpose I apply Sen’s ‘capabilities approach’ to development: ‘a process of expanding the real freedoms that people enjoy’ (Sen, 1999), understanding it as a process, not an outcome; focusing on freedom of choice in all spheres – the personal, social, economic and political; putting people at the centre of development; and allowing people themselves to define what they value (Tufte citing Sen, 1993).

Blog 2: Cloudy with a chance of migration

Behind the children’s film reference, this blog explored the endeavour of the Danish Refugee Council to use Big Data to forecast migratory flows, with the objective to better inform the humanitarian sector and thus enable more effective responses to crisis scenarios, specifically in terms of refugee support. Whilst on the one hand, the initiative is laudable and has potential to improve crisis response, with the protection and respect of people at the centre of DRC’s mission, the example flags some concerns when considering how to use Big Data in development.

Firstly, the risk of how data might be misappropriated has been a challenge discussed by DRC during the iterative design process, one which explains perhaps why access is not yet public – though this is the intention. It is therefore something we must continue to keep in mind for other applications of Big Data in development, echoing the critical questions posed by academics such as Boyd and Crawford, (2012) as to who gains access and who is able to extract value from data. Whilst the Foresight example uses open-source data and thereby is theoretically replicable by anyone with access to an internet connection (albeit someone highly skilled in algorithm development), data is a high value commodity and thus synonymous with power (Tufte citing Leistert 2013).

Data quality, from how it is sourced to its coverage and quality, is also a challenge. DRC took the pragmatic decision to use quantitative global datasets (e.g. UN and World Bank), because this provides comparable data around the world. However this choice also limits the end result’s potential accuracy. Whilst the initial testing incorporated qualitative data, the inclusion of the lived-experience interviews in the final algorithm is less clear which calls the ‘people-centred’ element of such Big Data into question. This example is symbolic of the limitations of using Big Data to inform development decisions because of the difficulty in ‘humanising’ data and placing people at the centre. When qualitative data is limited and qualitative and quantitative data collection are comparable in neither scale nor scope, in particular in countries where internet penetration is lower, generally speaking, lower and middle income countries (LIC, MIC), limiting raw data and making mass-collection (e.g. via surveys) more challenging.

The Overseas Development Institute’s recent blog on the data gap on attitudes to migration in LIC and MIC gives an excellent analysis of a migration-related data gap and further proves the need to address what Cinnamon refers to as ‘data divides’, encompassing access to data, representation of the world as data and control over data flows. If we are to aspire to employ Big Data to impact positively on people, their choices, capabilities and freedoms, we must take care to consider the core elements of data access, quality, coverage, how it is mined and for what purpose, so that we may walk the thin line between socially beneficial use and surveillance and control (Taylor, 2016).

Despite these concerns raised about Big Data (and there are more besides), I return to the idea that social change comes from knowledge and understanding. Given also that disaster-affected communities increasingly become “digital communities” (Meier, 2015) we should therefore embed technology and data in migration and development policies, preparation, and processes – particularly crisis-related scenarios. Whilst we clearly need data to inform action, we must aspire to gathering, analysing and using data (and mitigating data bias) in a respectful way that places people at the centre. DRC’s Foresight design process can therefore serve as a strong example of attempting to combine quantitative and qualitative data with this in mind.

Blog 3: Migration’s Social Dilemma

From Big Data analysis, to social media, one of the sources for data mining of public opinion. My third post introduced a plethora of examples of social media used for positive social change in relation to migration and development. I presented examples of social media used for awareness raising, accountability, deterritorialised community building, cultural identity preservation, crisis response, information sharing and preventing human trafficking. However, I also highlighted examples of ways social media can be used to limit the choices and freedoms of migrants, drawing the conclusion that social media can be both a development vector and an antagonist, according to intention.

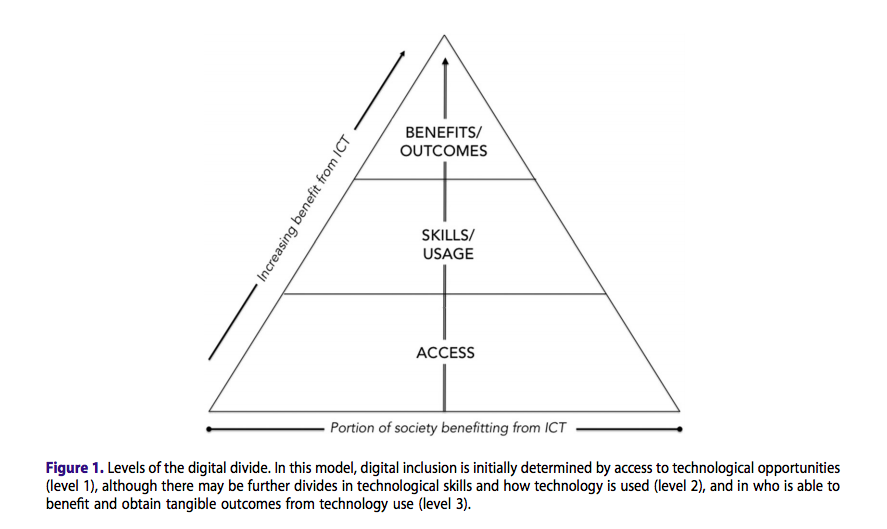

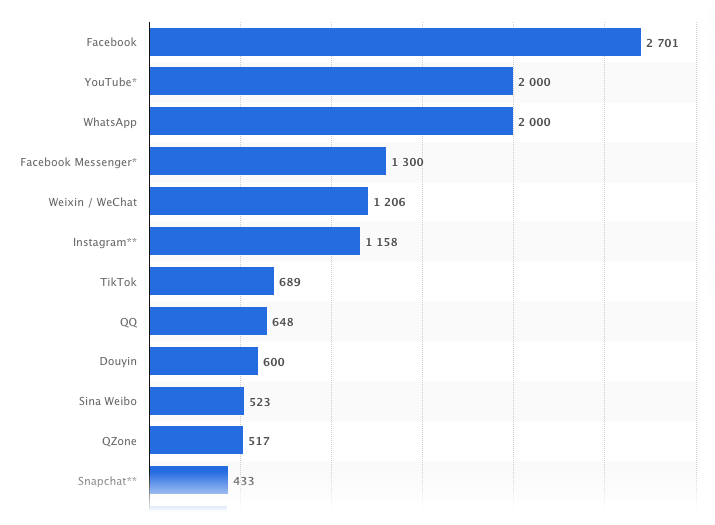

Academically, we might consider social media as a modern-day public sphere and therefore see discourse on migration and development on these platforms as having potential influence in holding governments to account. There is evidence of social media activity influencing policy ‘for good’, but the fraught topic of migration has often seen social media drive far-right discourse mainstream and influence policy accordingly, as discovered by University of Dublin in an analysis of 7.5 million tweets about migration between 2015-16. The impact of the positive narratives on migration, like those included in my list, do not get a look in when – as the report puts it – “rather than contributing to openness and democratisation, social media platforms have been used to attack the most vulnerable people in society like refugees fleeing war, while stories of those impacted by the crisis on the other hand failed to gather attention.” Furthermore, the report marks elite politicians, media, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as the most prominent actors on Twitter, weakening the idea of social media as home to a truly public sphere. In fact, more broadly, we should be mindful that, whilst 3.8 billion use social media, this is predominantly in High Income Countries, and disproportionate in terms of gender and generational balance. Moreover, the internet is dominated by the English language, and algorithms ‘curate’ content – including paid-posts – for users based on their data profiles. Social media as a vector of development is therefore limited to those who have access to it, or are in the extended (in-person) network of social media users.

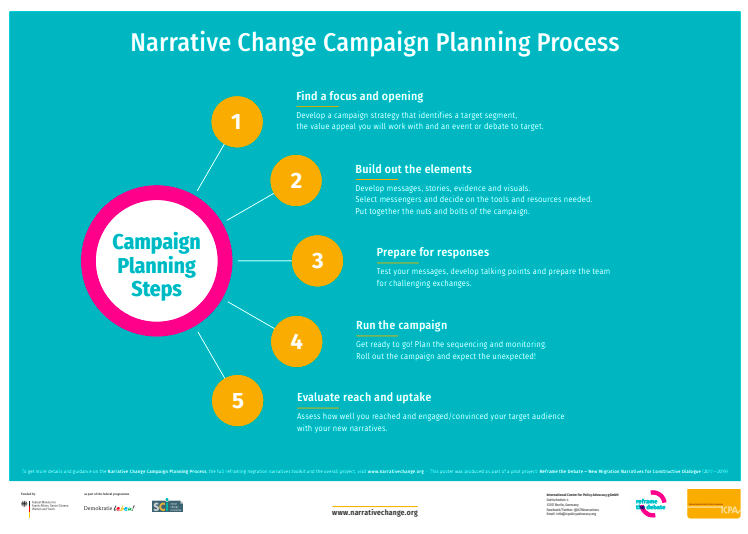

The difficulty of measuring impact of social media campaigning remains a challenge in leveraging (and proving the role of) social media for development. Whilst there are many on- and offline campaigns targeting migrants, IOM’s report on a pilot study into the efficacy of Facebook campaigns targeting potential irregular migrants is a first step in filling this knowledge gap. I believe IOM’s concluding remark, that intervention activities such as online campaigns do not always translate into immediate, observable impacts, is crucial to recall for all ComDev practitioners, no matter the subject matter. Perhaps because of this difficulty of evaluation, it is even more pressing to refer to academic study of social media more broadly, in order to plan, implement and assess communication migration interventions on social media.

In fact, all of the above considered, we might be better to focus on the use of social media to hold traditional humanitarian actors to account as they are found to be more active on social media, as well as generally being based in regions with greater access to the internet and more social media-active citizens . The recent discourse held about and by humanitarian actors on social media including self-satire (Schwarz & Richey, 2019) and meme culture (Chonka, 2019), may, in part, be responsible for organisational-level research into communication by and about humanitarians (Newman, 2017), including representation of refugees (Etem, 2020). If influencing an elite few is the most tangible use of social media for social change in the migration and development nexus, whilst important, it is understandable that it does not feature explicitly in regional and global policy frameworks as an ICT4D.

Nevertheless, with ever-expanding internet penetration and more people joining social media, the networks’ ability to facilitate higher interactivity and connectivity will merit further monitoring and review, as well as debate on how its data is managed with potential to feed evidence-based policy and practice to maximise its communication for migration and development. In addition to achieving (and monitoring) the Sustainable Development Goals.

Blog 4: Growing Europe: seeds of migration, digital soil, pruning language

The final post in my exploration of technology in migration and development beyond data collection on migration flows, as per the frameworks reviewed, covered the closing event of Growing Europe on migrant entrepreneurship. I introduced the different examples of entrepreneurs creating training and employment opportunities for refugees and migrant communities in the technology sector, but the resounding question for me from the events was: why is it important to stress migrant entrepreneurs? A question which clearly goes beyond the tech sector examples, but is a powerful one to consider in terms of the growing power of new/digital media.

In terms of ICT4D, the training and employment initiatives seem to fit with Alsop ad Heinsohn’s proposal to operationalise Sen’s capabilities approach. This is most clear in terms of empowerment (cited in Kleine, 2010), as the programmes offer participants the opportunities to build both their individual agency and human capital, thereby theoretically expanding opportunities for employment, ergo choice. Indeed, one could see the programmes as opportunities to build agency by improving the complete ‘resources portfolio’ of Kleine’s Choice Framework (Kleine 2010) whilst simultaneously allowing participants to overcome access barriers and structural constraints they might face without such accelerator programmes.

Furthermore, it could be argued that because the examples were created – and are run – by people with a migration background, their existence is both embodiment and driver of expanding choice, capability and freedom via technology. Continuation and replication of such projects has the potential to snowball these freedoms within migrant communities – for as long as the technology sector continues to expand. Finally, examples of projects supported and designed by the incubator elements of the projects demonstrated additional potential of Migrant Tech for positive social change. Nevertheless, as Migrant Tech is both service provider and product comparable to non-tech options, I conclude that it does not deserve direct inclusion at policy level, but should (and often is) included at implementation-level.

Previously, I proposed that the use of the ‘migrant’ label for entrepreneurs might be seen as a “narrative stepping stone to a stage when we don’t need the qualifying adjective”, in tech entrepreneurship and beyond. However, now I would refine this to be an aspiration for citizen discourse, rather than for research where disaggregation can be useful in providing evidence that feeds policymaking that promotes a capabilities approach including [migrant] entrepreneurship. Moreover, whilst migration remains a highly charged issue at national, regional and global levels, narratives that demonstrate migration to be a driver of positive social change are essential to counterbalance those that seek to influence the migration agenda based on fear mongering and lies. Celebrating and mainstreaming migrant entrepreneurship could be a step in the right direction when discussing migration in both private and public spheres.

Conclusion

My exploration into examples of ICT4D in the world of migration has shown that technology’s role in migration and development is as diverse as the people who move and their reasons for doing so. It has the potential to be employed for good and for ill.

How technology is included in national, regional and global policy frameworks is driven by political will, which, in democracies, is steered by citizen demand. Whilst the dominant rhetoric on migration is that of border control and migration flow restriction, policies will naturally reflect this, and technology as the major facilitator of our time will be recognised for its important role in achieving such objectives. However, a globally accepted holistic view of migration and its impact on societies should, hopefully, be reflected in policies, including a role for technology beyond monitoring numbers. Research on migration and development, including ComDev, should continue to build evidence, test ideas and challenge existing ICT4D in migration to ensure that ICT4D solutions are human-centred and context appropriate. As the world becomes increasingly globalised and digitally connected, ICT4D and migration will become ever more intertwined, needing further scrutiny on policies and practices at individual, organisational (private and public) and governmental levels.

Project reflection

This assignment has motivated me to actively engage in ongoing discourse around ICT4D at implementation level, whilst simultaneously allowing me to apply my academic studies to the field in which I work. It has been an excellent opportunity to marry the two – although shifting writing styles from more personal to academic has been a bit of a challenge!

As the task included promotion, it helped me to grow my professional network via LinkedIn and I am delighted to have had bilateral conversations with various organisations active in migration and development. I did not expect that my posts would generate this sort of connection, but have been really encouraged that they did. This experience inspires me to consider how I might continue to engage more proactively in public discussions on migration, development and technology beyond the end of this project.

Although we established a communication/project plan, the deviations we ended up making because of technical challenges, needing more time etc, reminded me of the need to be responsive and flexible in group work – a lesson very easily applied in a professional environment too.

Were I to repeat the assignment, I would consider the possibility of producing all the written content in advance, then organising a shorter more intense posting schedule, almost as an event in itself, with the opportunity for live conversations around each sub-topic. I think this could work quite well with a mini-series on a fairly narrow topic. However, it would likely only be possible with a pre-existing network and reputation, and therefore is an idea I am more likely to take forward at work.

[2498 words]

References

In lieu of footnotes, I have used hyperlinks to sources when the original is open access. Others are referenced in the text above and refer to the following source texts (list also includes relevant texts not directly referenced):

Chonka, P. (2019). The Empire Tweets Back? #HumanitarianStarWars and Memetic Self-Critique in the Aid Industry. Social Media + Society, October.

Etem, A.J. (2020). Representations of Syrian Refugees in UNICEF’s Media Projects: New Vulnerabilities in Digital Humanitarian Communication. Global Perspectives 1:1.

Kleine, D. (2010) ICT4WHAT?—Using the choice framework to operationalise the capability approach to development. Journal of International Development 22:5, 674–692.

Meier, P. (2015) Digital Humanitarians: How BIG DATA Is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Schwarz, K. & Richey, L.-A. (2019). Humanitarian humor, digilantism, and the dilemmas of representing volunteer tourism on social media, New Media & Society, 21:9, 1928-1946.

Tufte, T., (2017). Communication and social change. Polity, Cambridge.

White, B.T., (2015 – 2020) Refugee representation research.Singular Things

Narrative Change project (2017 – 2019)