From the inception of this blog, the group wanted to find a permeating theme that would hold our interests and subjects together. We decided to put people at the centre in our exploration of the relationship between ICT and development, and therefore agreed upon “ICT4 who?” as guiding question for the blog.

In my four posts I have focused on ICT for Indigenous People, which actually has its own acronym: ICT4IP (Information and Communication Technology for Indigenous People). This post will be an edited overview of the theme, case studies and issues brought up in my previous posts against the backdrop of relevant literature.

Acronym Agreements

Agreeing with several authors of the literature of this course (Heeks 2017, Sein et al 2019, Walsham 2017) I think it is important to break down this acronym in order to fully understand it, and more importantly make the best use of it. Here is my take on it.

What is [I] – information? To concretise this I go backwards in the equation regarding data-information relationships in my latest post and Heeks’ information value change (2017, 7-8). Information is basically processed data. It might sound simple, but the word process in this case opens up an entire new debate. Who is processing the data, how, for what purposes, following what norms? I will bounce back to this further down when discussing digital colonialism and Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

What is [C] – communication? Heeks (2017, 8) defines communication as the transmission of data. To have a more human perspective I would like to add the act of listening and dialogue important parts of the concept.

Let’s not overtheorise [T] – technology. I will let a summary of Heeks approach (2017, 9) guide my definition: technology is a non-human entity created with human knowledge to undertake certain tasks.

Now for the [D] – development. This might be the main debate within ICT4D field: what does the [D] encompass? It is a broad, multifaceted and contentious concept. (Bentley et al. 2019, 478; Walsham 2017, 1). Also looking back to our previous ComDev courses, this seems to be the complex concept. Has there ever been a true consensus? It can mean so much. Anyways, what seems clear is that one must define it in order for a successful implementation of ICT for “it”.

Personally, I also think it’s a tough cookie, especially in regard to Indigenous People. What has been imposed by development agendas and paradigms, with mottos like modernisation and economic growth, has often posed a holistic threat to the existence of Indigenous People, their territories, culture, languages etc. Scholars even say development has been a vehicle for colonialism.

Indigenous development

However, leaving the historically charged aspect of the word development, to make sense here, I will here define it as progress and social change/empowerment. But what is it that needs to be developed, progressed or socially changed for this group of people? Obviously, I am in no position to determine, but to understand the answer, one must listen. Listening is an important yet often-overseen part of communication.

What I hear is that Indigenous People want their basic human rights fulfilled, Good Life (Buen Vivir), to rise from socio-economic marginalisation, respect of their territorial rights etc. So, with my posts I wanted to examine whether this can be enabled by the use of ICT.

To do succeed, ICT must contribute to structural, high-level changes necessary to improve situation for Indigenous People. As I mentioned in my first blogpost, social media has played an important role for Indigenous movements. A recent study (Lupien 2020) on “Indigenous movements, collective action, and social media” in Latin America found several benefits from the use of ICTs for Indigenous organisations. This in terms of enhanced communication, access to information and visibility.

Some of the “high-level changes” presented by Heeks (2017, 14-16) are relevant in this aspect, namely connection, illumination and universalisation. Communication and universalisation enable connection, creation of networks and mobilisation. Illumination may be the observances and recordings of human rights violations captured on phones and shard on social media. Testimonies tell that this has made a great impact in the case the Mapuche people in Chile, who long have suffered oppression of state forces in form extra juridical killings. (Lupien 2020, 7).

Indigenous social movements have been a huge political force in Latin America. Poell & van Dijck (2018) leads an insightful discussion on the impacts of social media on organisation and communication of protest. Social media platforms enable horizontal networks and bottom-up, distributed forms of protest mobilisation, organisation, and communication. A collective identity of indigenity is connected worldwide, mass sharing hashtags, protest slogans and materials on social media. (Poell & van Dijck 2018, 1-2 & 7)

Participatory ICT4D Methods

My second post was about an initiative where ICT is used for the benefit of Indigenous Peoples safeguarding protected land. Well explicitly, the app is developed for environmental purposes, but Indigenous rights and environmentalism do have rather synergetic goals. One of the main challenge was how to design a user-friendly and mobile app, culturally and locally relevant, for people who may be illiterate or never used a smartphone. For the collected data to be useful, it has to be specific, so a challenge was also to find a function for complex categorisation in the simplest way possible. To realise this project, participatory ICT4D methods were used, here follows an extract from the research paper on the project:

We held a five-day initiation workshop in August 2014 with 34 participants, selected by the PLCN and coming from all four Cambodian provinces in which the PLCN operates. We employed participatory mapping to identify forest areas used by communities and defined the overall aim of the monitoring program in a series of focus group discussions. /… / The app was developed by a local IT company, based on the PLCN’s input during the workshop and its feedback on a first prototype decision tree presented on the last day of the workshop.

(Brofeldt et al 2018, 3)

According to Bentley et al (2017, 478), participatory ICT4D methods are becoming more a common and often have practical or emancipatory objectives, with attempt to empower and protect poor and marginalised populations. However, this emancipatory logic also requires long-term development solutions, which as I mentioned in the original blog post[link], was a main challenge for the project. In a reflexive manner, they reported that the maintenance of software/hardware and the digital data validation process, which continuously requires external support, interferring with the sustainability-level of the project.

Bentley et al (2017) further state that in general, there is a call for more culturally sensitive approaches with ICT4D as well as critical ICT engagement. On key factor of this is power and control over the design of ICT aimed for [D]. Their study opts for visual methods methodologies in participatory ICT4D, as it “enable even the most-marginalized of populations to formulate their thoughts and explain their ideas to researchers.” (Bentley et al 2017, 481).

The Digital Divide

Let’s move on to the so called flip-side of ICT: if it brings benefits, then those without ICTs were going to lose out. Or what Heeks says more accurately should be called the digital continuum, as the divide misleadingly gives the perception that the divide is binary. Keeping the acclaimed term but having in mind that in reality the divide is more a grey zone than black/white. (Heeks 2017, 85-88).

Many people in our global society do not have access ICT and/or fail to be able to enjoy how ICT can promote [D]. A study on technology access in the Philippines shows that Indigenous People are over‐represented in rural communities where connectivity is not available. Additionally, they noted that for important governmental communication platforms, such as citizen application, there’s a lack of Indigenous languages (Roberts & Hernandez 2019, 3). They conclude that marginalisation of Indigenous People in the Philippines is reflected and reproduced in technology use.

Besides socio-economic and geographical reasons there are other things that creates the divide. Manoeuvring and benefitting from this increasingly dominant digital dimension of our reality is more difficult for some than others. So beyond issues of poverty and connectivity, there are ontological, epistemological, linguistic, gender-based, ethnical, cultural, rhetorical, reasons for this. This is why the field of ICT4D needs such a plurality of disciplines for its research (Sein et al 2019; Walsham 2017).

Digital Colonialism

Understanding that the content, functionalities and design of this digital sphere comes predominantly from a rather narrow homogenic group (English-speaking, white men from Europe and North America) is important. This re-produces the social power-structures into the digital. This results in bias or even racist AI algorithms where facial recognition programming fails to identify “people of color” (especially women). Also understanding that the normative, public knowledge available on Wikipedia (the 5th most visited site in the world) is in vast majority written by the same homogenic group, is another key to understand the social power structures forming our digital sphere. (Decolonizing the Internet. Summary Report 2018)

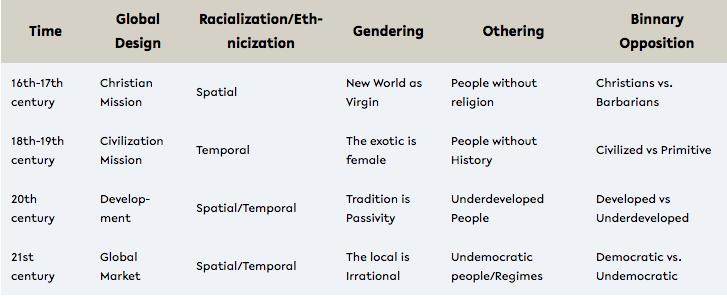

So we seem to have one dominant language, world-view, gender, culture etc. who produces and maintains the foundations and core of this new social sphere we live in. Consciously or unconsciously, the philosophy, epistemology, ontology, political and economic values of this homogenic group therefore spreads rapidly to all corners of the world.

Ideas on Decolonisation

Researches Jimenez & Roberts (2019) have studied the imposition process of norms/standards/values from the global North into the global South by studying practices of innovation hubs. Innovation hubs are described as places where technology entrepreneurs, experts and enthusiasts meet to collaborate on their latest apps, platforms and development projects. They state that “hubs in the global South were too closely modelled on the global North template of Silicon Valley start-up culture” which they say ”might lead to a lost opportunity to nurture indigenous approaches to innovation, as well as the risk of importing political and ideological values that drown out and silence local values and interests” (Jimenez & Roberts 2019, 2).

They imply that the practice of imposing foreign knowledge as valid and in turn invalidating indigenous knowledges, is labelled by postcolonial scholars as ‘epistemic violence’. Further, they suggest that having Indigenous approaches complementing the dominant (western/neoliberal) approach to innovation (within ICT) would be beneficial for the whole field. In their paper, they explore incorporation of values of the Andean-Indigenous philosophy Buen Vivir for an alternative approach to innovation, in opposition to the currently dominant economic model – neoliberalism.

It’s clear that neoliberal values such as individual enterprise, heroic inventors and the goal of private wealth accumulation stand in conflict with the Indigenous value systems. The authors of the paper promote the possibility of a plurality of legitimate paradigms around innovation.

Indigenous Data Sovereignty

If racism or colonialism easily gets translated into the digital sphere by programmers, then there’s also a risk that same thing happens in reverse, with the extraction of data. As mentioned earlier, information is processed, raw data. The mechanisms processing the data to produce information could arguably be influenced of cultural norms, world-views, race etc.

The field of data would also benefit from a decolonising approach, as Indigenous People often are excluded from data collection, processes and governance regarding themselves. (IDS). The Indigenous Navigator, discussed in my third post, is a contributory initiative to mend that issue.

The politics of data are embedded in ‘who’ has the power to make determinations and who controls the narratives surrounding indigenous peoples’ lives. Currently, it is not indigenous peoples themselves.

(Kukutai & Taylor 2016, 7)

My fourth post presented the subject of Indigenous Data Sovereignty, which also sometimes is referred to as a movement. According to Walsham (2017, 12) there’s a deficit on research of the “dark sides” of ICT4D. Issues of data security/justice regarding Indigenous People would be one of them. As mentioned in my post, data can be viewed as a capital resource. Therefore, it is important to implement proper political economy of data and socially equitable rule of law for data. (Taylor 2017)

Concluding thoughts

Starting out this project, I had zero experience with blogging, and almost zero experience with CMS in general. Looking for jobs in the ComDev field, I have noted a high demand of such skills, so the practical learning of this exercise was very welcomed from my side. The learning process of writing text in format of blog posts have been a rewarding practice for me, as I tend to have difficulties moving away from the default academic writing that I have grown so accustomed to in the past few years. This was an issue that arose at the position as Editorial Assistant Intern at IWGIA. I was assigned to write articles regarding COVID-19 and Indigenous People, and found it challenging to maintain a journalistic, smart yet simple language.

The theme of this module has provided me with a lot of food for thought, as I see a lot of potential but also obstacles when it comes to ICT4D. It has awakened in me a new approach and interest for the development field, inspired for the forthcoming choice of subject for the thesis writing for the spring. When it comes to ICT for Indigenous People, I have learned a lot while writing these blogposts. First and foremost, it is crucial to have cultural sensitivity when implementing ICT4D projects for Indigenous People, to avoid harmful impositions of values and structures from the global North. This, of course, goes for any development projects really.

References

- Bentley, Nemer, & Vannini (2019). “When words become unclear”: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D. AI & Society, 34, 477–493.

- Brofeldt, Argyriou, Turreira-García, Meilby, Danielsen, & Theilade (2018). Community-Based Monitoring of Tropical Forest Crimes and Forest Resources Using Information and Communication Technology–Experiences from Prey Lang, Cambodia. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 3(2).

- Heeks (2017). Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jimenez & Roberts (2019). Decolonising Neo-Liberal Innovation: Using the Andean Philosophy of ‘Buen Vivir’to Reimagine Innovation Hubs. In International Conference on Social Implications of Computers in Developing Countries (pp. 180-191). Springer, Cham.

- Kukutai & Taylor (2016). Indigenous data sovereignty: Toward an agenda. Anu Press.

- Lupien (2020). Indigenous Movements, Collective Action, and Social Media: New Opportunities or New Threats?. Social Media+ Society, 6(2),

- Poell & van Dijck (2018). Social Media and new protest movements. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, 546-561.

- Roberts & Hernandez (2019). Digital access is not binary: The 5’A’s of technology access in the Philippines. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 85(4), e12084.

- Sein, Thapa, Hatakka, & Sæbø (2019). A holistic perspective on the theoretical foundations for ICT4D research. Information Technology for Development 25:1, 7-25

- Taylor (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data & Society, 4(2)