ICT4D’s great promises:

Faith: innovative, game changing, can solve social, economic and infrastructural problems

Hope: fosters development, improves livelihoods and justice

Love: interpersonal mass medium , social networking relationships, connecting to loved ones

Luck: offers more opportunities, choices, no one is left behind.

My last blog post weaves together the loose threads of my exploration in the previous posts on Big Data, Facebook, Governance, Humanitarian Action and Development, and bundles them towards the role of ICT in development. Academic literature reveals: ICT4D is a vast field with a growing body of research. Theories are borrowed, adapted and merged to create a framework for the development informatics field. Thus, I have picked out a few aspects only, which I will investigate along the following questions:

Does the application of new technologies change relations of power or merely amplify existing inequalities? Will they be transcended? Become visible? Who is benefitting? Who is losing? What is data justice?

Faith

Buzzwords as data-driven, smart, innovative and game changing have been used to celebrate digital technologies as problem solvers. Big Data and AI were seen as key technologies to deal with all kinds of social, economic and infrastructural problems and solve them in the most efficient and effective manner. Optimism dominates about the potentials of ICT to improve livelihoods in low-income countries. Thus, the UN, development organisations and policymakers are promoting and funding plans and enterprises that aim to bolster or create digital economies and data is seen as a prerequisite for delivering the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, ensuring that no one is left behind.

In this post, the focus is on the ‘world’s economic margin’ (Mark Graham 2021) and the Global South.

Data – Hope and Danger

An increasing and diverse body of research has directed critical attention to data and its consequences. There is no doubt that data is needed for development and towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Research on digital inequalities is multi- faceted within development discourses and includes access to data, representation of the world as data, and control over data flows (Cinnamon 2019).

While data is of great importance, ICT might also have unintended consequences. As any other technology, it is not neutral, but ‘mirrors the societies that create and use it,’ (Annan-Callcott, 2019:10). Data has been discussed in relation to social divides and questions have been raised about whether data related disparity can be corroborated by existing social inequalities.

Linnet Taylor (2021) dismisses the idea that data technologies fill a singular position in society and that their contributions and problems should be examined as a category of their own. ’Instead,’ she writes, ‘data technologies both reflect and construct justice and injustice in ways that can be understood through analytical lenses we already possess (Taylor 2021:14).’ She argues that, since digital inequalities reflect existing inequalities and mirror social divides, analytical tools to measure inequality can also be used to assess digital inequalities.

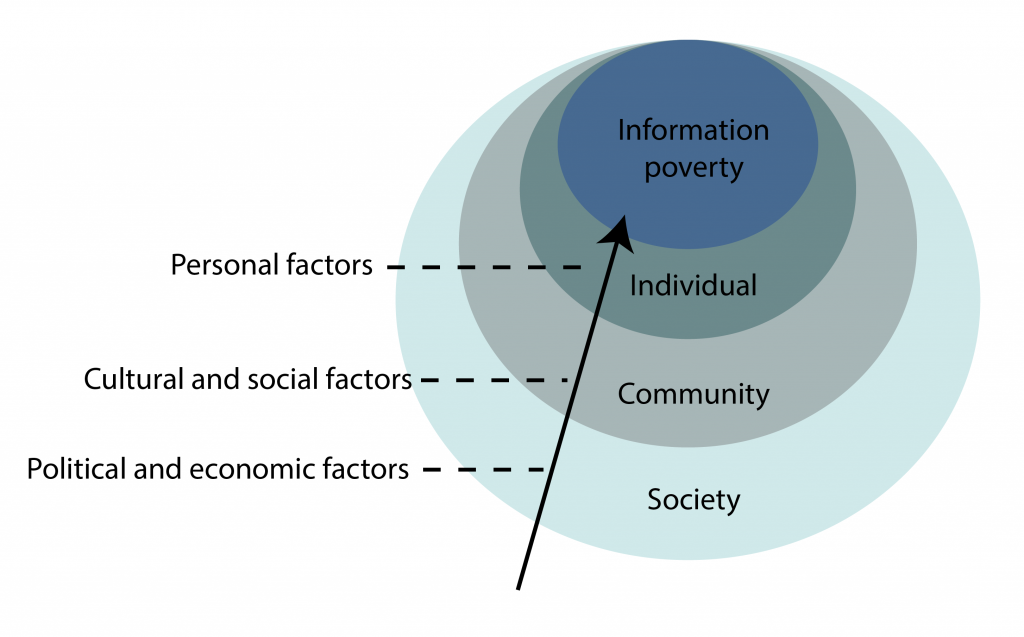

Digital inequalities are represented as levels of digital divide and include access to data and technological skills. Moreover, as Cinnamon argues, that who is able to use and benefit from data is the important question to investigate. He expands the notion of digital divide and draws on a model of information poverty, which is ‘shaped by cumulative effects of structural inequalities at the societal scale’ (Cinnamon 2019: 215-218).

The capability to access and benefit from data resources is formed by societal structures and dynamics, as well as communities, and individual capabilities and can be related to ‘information inequalities’ or extended to ‘information poverty’ for information ‘haves and have nots’(Cinnamon 2019: 215-218).

Data-poor and no-data settings pose a huge challenge in many countries. The OECD Report (2017) lists a number of countries which lack data in relation to the SDGs, eg. 77 countries have inadequate poverty data. In addition, an acute knowledge problem lies in the analysis of economic development, because GDP numbers and other statistics, often regarded as facts, are not facts, but products, and when they are produced under difficult circumstances, they might provide a biased picture about income and growth, as well as the real conditions of the poorest in those countries, as Jerven reports in his book ‘Poor Numbers’ (2013).

‘A recent example comes from Ghana where a change in the statistical material that underlies the calculation of GDP meant that the country’s GDP was revised upwards to the extent that Ghana’s recorded GDP per capita almost doubled. In effect, overnight the country was reclassified from a low-income country to a lower-middle-income country. The knowledge problem does have implications for governance (Jerven in The Lancet, 2014).’

Love – Connectivity?

Much of Africa is considered to lack connectivity. On one side, connectivity is of utmost importance to to connect with one’s loved ones, family and friends, as the recent lockdown of Facebook and WhatsApp demonstrated, on the other side, the connective imperative in ICT4D can also be considered in relation to the violent colonial history of connectivity. In a critical discourse links are made between the connectivist discourse in ICT and colonial enterprises in which many colonized people lost their lives, as the building of the Uganda Railway in British East Africa around the 1900s. Furthermore, the development connectivity project post–World War II was heavily motivated by the modernization theory with its adaption of new technology approach (Graham, M. (ed.) 2019, 341-342).

Heeks (2021: 772-774) adds another perspective to the discourse about data technologies which he coins ‘adverse digital incorporation’. He argues that the increasing cause of inequality in the global South is not exclusion from digital systems, but inclusion in a digital system that permits a more-advantaged group to extract excessive value from the production and resources of another, less-advantaged group.

One of many example for ‘adverse digital incorporation’ is the GIG economy in South Africa with tens of thousands of gig workers – performing tasks for digital platforms like Uber, Uber Eats and SweepSouth. Since those platforms regard their workers as independent contractors rather than employees, almost all find themselves earning below the living wage in normal times and going hungry in times of Covid – 19, as the platform did not pay their workers a penny as compensation for the zero income situation, as Fairwork reports.

A fine line

There is a fine line between the just use of data technologies for social benefits and surveillance and control leading to data-driven discrimination. Interacting attributes as socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, race and place of origin determine who is represented, how data is collected in which databases, and how data technologies use data to generate insights and influence decisions. Data is often protected. Transparency and access to all data is many times fractionalized along social, economic and geographic borders.

Taylor (2017:2-14) argues that the poor, often lower caste and/or female, have always borne the burden of data-driven discrimination. Contrary, well-off citizens get away, and find their ways with technology and the bureaucracy – a way of formalising precarity.

The Aadhaar card in India is one example which contains several facets of data-driven discrimination, as well as state surveillance: The Indian Aadhaar Card is a digital identification system in which more than 1 billion people were enrolled in less than 6 years. It is linked to employment systems and public distribution, old age pensions and also to services as getting a mobile number, opening a bank account etc.

The world bank blog reports that ‘The Indian government now saves billions of dollars every year, through reduced fraud and leakages in the Direct Benefit Transfer regime.’ The world bank celebrates this as an example to leapfrog to the digital economy in which users are in control of personal data and are empowered to use this data to improve their lives (World bank blog, Nilekani N. 2018) and recommends other developing countries to use this as an example to empower and improve people’s lifes. (Interesting to see that the author of the World bank blog himself is a member of the private data industry.)

The Aadhaar card was thought to curb welfare fraud and corruption, which especially affects the poor and marginalised Indians below poverty line, who depend on government benefits as food rations. In reality, the poorest are the worst served by the system. Many poor who work with stone and cement have their fingerprints erased due to the work conditions, as Taylor (2017) writes, plus undernutrition doesn’t allow the iris to be scanned properly. Each family has only got one member registered to draw rations and if this member is unavailable or sick, the family goes hungry. The backup authentication system sends a password to the registrant’s mobile phone, which is probably the man in the family. It is known that women own a lot less phones than men. The system seems to reinforce the existing gender hierarchy, adding additional discrimination for women in India.

In addition to the flaws described above, the Aadhaar card was implemented without a legal framework and in the absence of a privacy law, which raised serious concerns about state surveillance and led to several court cases. Pranesh Prakash, a lawyer and policy director of the Centre for Internet and Society said: “This implies that the core biometric information, collected or created under the Aadhaar Act, may be used for purposes other than the generation of Aadhaar numbers and authentication ‘in the interest of national security.” In 2019, the Times of India reported, that a Face recognition feature was connected to the Aadhaar card, which adds another critical question to the Aadhaar Card, the one of state surveillance.

Luck – An ICT4D framework related to the capability approach?

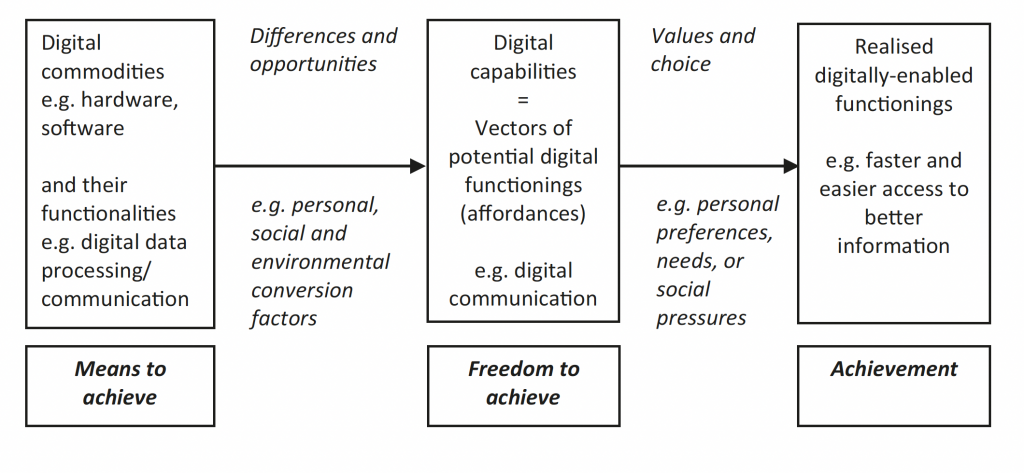

Heeks (2017) rolls out and connects the capability approach of Indian economist and philosopher, Amartya Sen, to an ICT framework in order to develop an approach for ICT4D which goes far beyond technological achievements.

Sen has expressed the need for a focus on freedoms for people to achieve their capabilities, rather than simply focusing on metrics such as GDP or income-per-capita. Sen defined as a core idea of freedom ‘what the person is free to do and achieve in pursuit of whatever goals or values he or she regards as important’ (Sen 1985:203). Sen argues that development entails a set of 5 distinct freedoms: political freedoms, economic facilities, social opportunities, transparency guarantees, and protective security. Amartya Sen explains in an undated interview that there is no priority in the sequence, but the freedoms should be seen as combinations.

In connection to in ICT4D, Sen’s notion of potential capabilites and realised freedoms can be illustrated with the children downloading music on their phones and the midwives making personal phone calls, which are achievements important to them and of value (Heeks 2017).

‘Instead of asking “What is the impact of ICTs?” in some general sense, a capabilities-oriented evaluation would ask, “To what extent do ICTs help people achieve the things they value doing or being?” (Heeks 2017:243).

The capability approach mapped onto ICT4D, could mean that an individual is able to select from particular digital functions and achieve: better communication, journeys avoided, increased knowledge, faster and easier access to better information etc. In addition, this framework moves beyond only focusing on ICT infrastructure, the capability to access and use ICT is just a first step. The framework moves, according to Heeks, beyond Sen’s ‘ability and freedom’ to reflect on what is actually achieved by using ICTs. It also identifies the enablers and boundaries – that hinder the technology’s efficient use; and also the personal choices people make about how to use ICTs, thus connecting to ideas about motivation. (Heeks 2017: 238-245).

Hope – Data justice for Development?

The sustainable development paradigm is shaped around the two core issues of environmental sustainability and social justice for those marginalised by inequality. Its much-repeated definition comes from the 1987 UN report, Our Common Future, also known as the Brundtland Report.

On the one hand a lot of discussion on justice in ICT has focused on increasing access for the Global South, on the other hand on the innovative solutions big data and AI seem to provide to complex social problems. Technologies were developed in the military sphere and corporations such as Google and Microsoft who produce and own images and control what we see and thus, how we see the world. It seems that transparency is key to data justice: Lifting the veil, sharing the programming of algorithms and the process of production is a process of inclusion and exclusion.

Drawing on Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach Heeks & Renken (2016:1) state

‘People may have access to justice in theory but not in practice because they lack the capabilities to do so’.

In their discussion on ‘data justice for development’, Heeks & Renken (2018) connect two schools of thoughts, justice in development and data justice, with different perspectives instrumental, procedural, and distributive/rights-based. As data systems in international development use code, algorithms and standards of data which have already accumulated parts of the social fabric that may lead to unjust outcomes, they are arguing for change in data-intensive development institutions, based on justice-based laws and policies.

The authors develop a complex agenda around a data-intensive development that situates issues of justice at its center, connected to a social movement which would challenge old structures and provide alternatives.

Reflection on my learning:

No doubt data is needed for development. No decisions, no action can be taken without data and no evaluations made. Increased ICT comprises a diverse range of tools that have infinite uses in infinite contexts.

There is not a single narrative – no good or bad, but a diversity of stories about digital technologies. There is also a fine line between the beneficial use of data and surveillance and control. Using private companies to serve governments and act as gatekeepers of social knowledge, as the example of the Indian Aadhaar Card and Facebook (in my previous posts) show, pose certain threats to democracies. Data are constructed by humans and that is where biases come in, as I explored in a former post. Data can’t be regarded as neutral facts and understood as reality, but as constructed artefacts, which mirror and reinforce existing social relations and inequalities. Thus, digitally-related inequalities have a close connection to social and structural inequalities. Providing technology as ‘internet connection’ doesn’t solve these inequalities and ‘connection’ can be related to a brutal colonial history, which was enslaving people to build connections, as the railway in Uganda.

Although digitally-related inequality is likely to be a major challenge, the problems linked to digital systems will not be confined to inequality, more examples are the growing carbon footprint of digital systems and the conditions of labour in the GIG economy (Heeks, 2017).

I came in contact with the no-data challenge in my work on ‘social security for unorganized workers’ in India. There was practically no data about 94% of all labour in India, the huge informal workforce. This has to be seen in close connection to the question who is represented by data and who is not and touches on questions of power, caste and poverty. In India, the development program had to be started with a training program for social workers to collect data by going from house to house and walking over the fields.

The chapter of learning about informatics and development is not closed for me, as always, time was too short to explore it in depth. But it’s a start and the blog format helped a lot, since writing became somehow easier. It was just a beginning to explore more on ITC4D.

References

Birhane, A. 2019: Real Life Mag, 9 July.

Brundlandt Report 1987, accessed 1.11.2021 https://www.netzwerk-n.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/0_Brundtland_Report-1987-Our_Common_Future.pdf

Cinnamon, J. 2019: Information Technology for Development: Routledge, accessed 3.11.2021

https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1650244

Fairwork, Oxford Internet Institute: accessed 10.11.2021https://fair.work/en/fw/publications/gig-workers-platforms-and-government-during-covid-19-in-south-africa/#continue

Graham, M. (ed.) 2019: Stefan Ouma, Julian Stenmanns, and Julia Verne. Ottawa, ON/Boston, MA: IDRC/MIT Press.

Heeks, R. 2021: Conceptualising Adverse Digital Incorporation FROM DIGITAL DIVIDE TO DIGITAL JUSTICE IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH: CONCEPTUALISING ADVERSE DIGITAL INCORPORATION, accessed 1.11.21 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3907633

Heeks, R. 2017: Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) . Milton : Taylor & Francis Group, 2017 Abingdon: Routledge.

Heeks R. & Renken J. 2016: Data justice for development: What would it mean? Sage, accessed 1.11.2021

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0266666916678282

Jerven, M. 2014: Poor numbers and what to do about them, The Lancet, accessed 10.10.2021

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60209-9/fulltext

Jerven M. 2013: Poor numbers: how we are misled by African development statistics and what to do about it. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

Kwet M. 2021: Digital colonialism: the evolution of American empire, accessed 2.10.2021, https://roarmag.org/essays/digital-colonialism-the-evolution-of-american-empire/

Taylor, L.:What is data justice? 2017: The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally, Big Data & Society, Sage, 2.10.2021 https://journals.sagepub.com/home/bds

Taylor, L.; Sharma, G.; Martin, A.; Jameson, S. 2021: Data justice and COVID-19, Tilburg University, accessed 10.9.2021, https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/708bf13e-db74-4543-bc35-6c79c9c39ba7

Realllife mag, accessed 2.10.2021 https://reallifemag.com/the-algorithmic-colonization-of-africa/

OECD 2017, Development Co-operation Report 2017 Data for Development © OECD 2017, accessed 2.10.2021 https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/dcr-2017-6-en.pdf?expires=1636035072&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=DA4C278D8454763E64BACEA2DCD2BD69

WHO, accessed 2.10.2021

Nilekani N. 2018, Giving people control over their data can transform development, Worldbank blog, accessed 2.10.2021, https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/giving-people-control-over-their-data-can-transform-development

Read R.; Taithe B. & Mac Ginty R. 2016: Data hubris? Humanitarian information systems and the mirage of technology. Routledge. Third world quarterly.

Sen, A. 2001. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

And in an interview (without date) accessed 2.10.2021

https://www.removingunfreedoms.org/five_freedoms.htm

Annan-Callcott, G. 2019: Technology mirrors the societies that use it, accessed 20.10.2021

https://www.projectsbyif.com/blog/technology-mirrors-the-societies-that-use-it/

Davos 2020: Yuval Noah Harari “ Rise of Digital Dictatorships by Corporations and Governments”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_relationship

https://gizmodo.com/how-whatsapp-swallowed-half-the-world-1847805134

My related blog posts:

Big Data Learning curve (for Dummys like myself)

- https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group8/2021/09/29/strawberry-pop-tarts-and-big-data-why-does-it-matter-for-development/

- https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group8/2021/09/29/how-can-algorith…s-and-unfairness/

- https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group8/2021/10/13/the-promises-of-…-for-development/

Facebook and WhatsApp

- Sorry for the disruption

- Is Facebook still trending or does its power crumble ? Who regulates?

- Facebook and YouTube delete accounts: Germany’s democracy strengthened or endangered?

Humanitarian Action

Podcast 01: A talk with Warren Lodge, owner of a small media enterprise in Cape Town, South Africa and an activist.

Podcast 02: A Talk with Hussein Alwaday on Big Data for Development